Hundreds of Police Killings Go Undocumented By Law Enforcement And FBI (#GotBitcoin)

When 24-year-old Albert Jermaine Payton wielded a knife in front of the police in this city’s southeast corner, officers opened fire and killed him. Hundreds of Police Killings Go Undocumented By Law Enforcement And FBI (#GotBitcoin)

Related:

Why Are Blacks Afraid To Push For Complete Police Reform?

Poll: Could The Private Sector Replace Police Departments?

Petition: Let The Private Sector Replace Police Departments

Started In 1850, This Was Once The Largest Private Law Enforcement Organization In The World

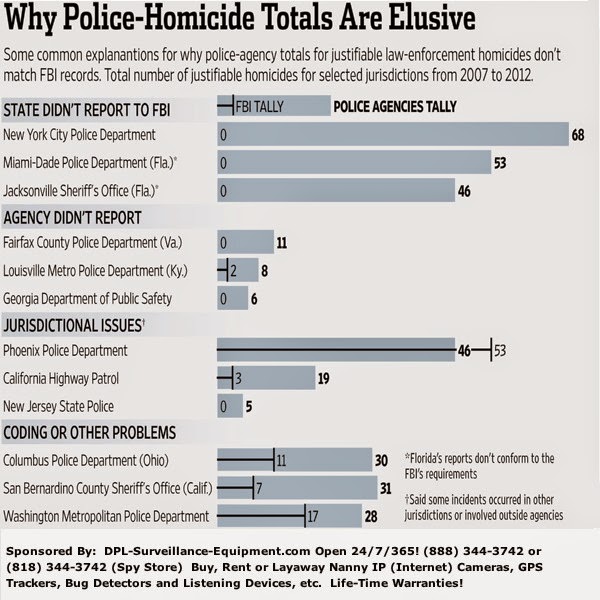

An analysis of the latest data from 105 of the country’s largest police agencies found more than 550 police killings during those years were missing from the national tally or, in a few dozen cases, not attributed to the agency involved. The result: It is nearly impossible to determine how many people are killed by the police each year.

Public demands for transparency on such killings have increased since the August shooting death of 18-year-old Michael Brown by police in Ferguson, Mo. The Ferguson Police Department has reported to the FBI one justifiable homicide by police between 1976 and 2012.

Law-enforcement experts long have lamented the lack of information about killings by police. “When cops are killed, there is a very careful account and there’s a national database,” said Jeffrey Fagan, a law professor at Columbia University. “Why not the other side of the ledger?”

Police can use data about killings to improve tactics, particularly when dealing with people who are mentally ill, said Paco Balderrama, a spokesman for the Oklahoma City Police Department. “It’s great to recognize that, because 30 years ago we used to not do that. We used to just show up and handle the situation.”

Three sources of information about deaths caused by police—the FBI numbers, figures from the Centers for Disease Control and data at the Bureau of Justice Statistics—differ from one another widely in any given year or state, according to a 2012 report by David Klinger, a criminologist with the University of Missouri-St. Louis and a onetime police officer.

To analyze the accuracy of the FBI data, we requested internal records on killings by officers from the nation’s 110 largest police departments. One-hundred-five of them provided figures.

Those internal figures show at least 1,800 police killings in those 105 departments between 2007 and 2012, about 45% more than the FBI’s tally for justifiable homicides in those departments’ jurisdictions, which was 1,242, according to the our analysis. Nearly all police killings are deemed by the departments or other authorities to be justifiable.

The full national scope of the underreporting can’t be quantified. In the period analyzed, 753 police entities reported about 2,400 killings by police. The large majority of the nation’s roughly 18,000 law-enforcement agencies didn’t report any.

“Does the FBI know every agency in the U.S. that could report but has chosen not to? The answer is no,” said Alexia Cooper, a statistician with the Bureau of Justice Statistics who studies the FBI’s data. “What we know is that some places have chosen not to report these, for whatever reason.”

FBI spokesman Stephen G. Fischer said the agency uses “established statistical methodologies and norms” when reviewing data submitted by agencies. FBI staffers check the information, then ask agencies “to correct or verify questionable data,” he said.

The reports to the FBI are part of its uniform crime reporting program. Local law-enforcement agencies aren’t required to participate. Some localities turn over crime statistics, but not detailed records describing each homicide, which is the only way particular kinds of killings, including those by police, are tracked by the FBI. The records, which are supposed to document every homicide, are sent from local police agencies to state reporting bodies, which forward the data to the FBI.

Our Analysis Identified Several Holes In The FBI Data

Justifiable police homicides from 35 of the 105 large agencies contacted by us didn’t appear in the FBI records at all. Some agencies said they didn’t view justifiable homicides by law-enforcement officers as events that should be reported. The Fairfax County Police Department in Virginia, for example, said it didn’t consider such cases to be an “actual offense,” and thus doesn’t report them to the FBI.

For 28 of the remaining 70 agencies, the FBI was missing records of police killings in at least one year. Two departments said their officers didn’t kill anyone during the period analyzed by us.

About a dozen agencies said their police-homicides tallies didn’t match the FBI’s because of a quirk in the reporting requirements: Incidents are supposed to be reported by the jurisdiction where the event occurred, even if the officer involved was from elsewhere. For example, the California Highway Patrol said there were 16 instances in which one of its officers killed someone in a city or other local jurisdiction responsible for reporting the death to the FBI. In some instances reviewed, an agency believed its officers’ justifiable homicides had been reported by other departments, but they hadn’t.

Also Missing From The FBI Data Are Killings Involving Federal Officers.

Police in Washington, D.C., didn’t report to the FBI details about any homicides for an entire decade beginning with 1998—the year the Washington Post found the city had one of the highest rates of officer-involved killings in the country. In 2011, the agency reported five killings by police. In 2012, the year Mr. Payton was killed, there are again no records on homicides from the agency.

D.C. Metropolitan Police Chief Cathy Lanier said she doesn’t know why the agency stopped reporting the numbers in 1998. “I wasn’t the chief and had no role in decision making” back then, said Ms. Lanier, who was a captain at the time. When she took over in 2007, she said, reporting the statistics “was a nightmare and a very tedious process.”

Ms. Lanier said her agency resumed its reports in 2009. In 2012, the agency turned over the detailed homicide records, she said, but the data had an error in it and was rejected by the FBI. She referred questions about why the department stopped reporting homicides in 1998 to former Chief Charles H. Ramsey, now head of the Philadelphia Police Department. Mr. Ramsey declined to comment.

In recent years, police departments have tried to rely more on statistics to develop better tactics. “You want to get the data right,” said Mike McCabe, the undersheriff of the Oakland County Sheriff’s Office in Michigan. It is “really important in terms of how you deploy your resources.”

A total of 100 agencies provided us with numbers of people killed by police each year from 2007 through 2012; five more provided statistics for some years. Several, including the police departments in New York City, Los Angeles, Philadelphia and Austin, Texas, post detailed use-of-force reports online.

Five of the 110 agencies contacted, including the Michigan State Police, didn’t provide internal figures. A spokeswoman for the Michigan State Police said the agency had records of police shootings, but “not in tally form.”

Big increases in the numbers of officer-involved killings can be a red flag about problems inside a police department, said Mike White, a criminologist at Arizona State University. “Sometimes that can be tied to poor leadership and problems with accountability,” he said.

The FBI has almost no records of police shootings from departments in three of the most populous states in the country—Florida, New York and Illinois.

In Florida, available reports from the Florida Department of Law Enforcement don’t conform to FBI requirements and haven’t been included in the national tally since 1996. A spokeswoman for the state agency said in an email that Florida was “unable” to meet the FBI’s reporting requirements because its tracking software was outdated.

New York revamped its reporting system in 2002 and 2006, but isn’t able to track information about justifiable police homicides, said a spokeswoman for the New York State Division of Criminal Justice Services. She said the agency was “looking to modify our technology so we can reflect these numbers.”

In 1987, a commission created by then-Governor Mario Cuomo to investigate abuse of force by police found that New York’s reports to the FBI were “inadequate and incomplete,” and urged reforms to “hold government accountable for the use of force.” The spokeswoman for the state criminal-justice agency said it isn’t clear what the agency did in response back then.

Illinois only began reporting crime statistics to the FBI in 2010 and hasn’t phased in the detailed homicide reports. “We cannot begin adding additional pieces because we are newcomers to the federal program,” said Terri Hickman, director of the Illinois State Police’s crime-reporting program. Two agencies in Illinois deliver data to the FBI: Chicago and Rockford.

In Washington, D.C., councilman Tommy Wells held two hearings this fall on police oversight. He said he was surprised that the department hadn’t reported details of police killings to the FBI. “That should not be a challenge,” he said.

More than two years after the knife-carrying Mr. Payton was shot and killed by D.C. police, his mother, who witnessed the killing, said she is still looking for answers. Helena Payton, 59, said her son had many interactions with local police because of what she said was his mental illness. “All the cops in the Seventh District knew him, just about,” she said.

The officers who arrived that Friday afternoon in August, in response to a call from Mr. Payton’s girlfriend, had never dealt with her son, she said. According to Ms. Payton, her son walked outside holding a small utility knife. As he approached the officers, they fired dozens of bullets at him, she said. He died soon after.

The U.S. attorney’s office is reviewing the incident, as is customary in all police shootings in Washington. A spokesman for the office declined to comment on the status of the case. The Washington police department, citing the continuing investigation, declined to provide the officers’ names, a narrative of what happened, or basic information usually included in the reports to the FBI, such as the number of officers involved in the shooting.

The officers involved are back on duty, according to D.C. authorities, but the case isn’t closed.

Updated: 5-30-2020

Federal Agencies Are Failing To Report A Range Of Crime Statistics To the FBI’s National Database

The gaps in data damage efforts to understand the nature and scope of violence driven by racial and religious hatred.

In violation of a longstanding legal mandate, scores of federal law enforcement agencies are failing to submit statistics to the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s national hate crimes database, ProPublica has learned.

The lack of participation by federal law enforcement represents a significant and largely unknown flaw in the database, which is supposed to be the nation’s most comprehensive source of information on hate crimes. The database is maintained by the FBI’s Criminal Justice Information Services Division, which uses it to tabulate the number of alleged hate crimes occurring around the nation each year.

The FBI has identified at least 120 federal agencies that aren’t uploading information to the database, according to Amy Blasher, a unit chief at the CJIS division, an arm of the bureau that is overseeing the modernization of its information systems.

The federal government operates a vast array of law enforcement agencies—ranging from Customs and Border Protection to the Drug Enforcement Administration to the Amtrak Police—employing more than 120,000 law enforcement officers with arrest powers. The FBI would not say which agencies have declined to participate in the program, but the bureau’s annual tally of hate crimes statistics does not include any offenses handled by federal law enforcement. Indeed, the problem is so widespread that the FBI itself isn’t submitting the hate crimes it investigates to its own database.

“We truly don’t understand what’s happening with crime in the United States without the federal component,” Blasher said in an interview.

At present, the bulk of the information in the database is supplied by state and local police departments. In 2015, the database tracked more than 5,580 alleged hate crime incidents, including 257 targeting Muslims, an upward surge of 67 percent from the previous year. (The bureau hasn’t released 2016 or 2017 statistics yet.)

But it’s long been clear that hundreds of local police departments don’t send data to the FBI, and so, given the added lack of participation by federal law enforcement, the true numbers for 2015 are likely to be significantly higher.

A federal law, the 1988 Uniform Federal Crime Reporting Act, requires all U.S. government law enforcement agencies to send a wide variety of crime data to the FBI. Two years later, after the passage of another law, the bureau began collecting data about “crimes that manifest evidence of prejudice based on race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, or ethnicity.” That was later expanded to include gender and gender identity.

The federal agencies that are not submitting data are violating the law, Blasher told us. She said she’s in contact with about 20 agencies and is hopeful that some will start participating, but added that there is no firm timeline for that to happen.

“Honestly, we don’t know how long it will take,” Blasher said of the effort to get federal agencies on board.

The issue goes extends far beyond hate crimes—federal agencies are failing to report a whole range of crime statistics, Blasher conceded. But hate crimes, and the lack of reliable data concerning them, have been of intense interest amid the country’s highly polarized and volatile political environment.

ProPublica contacted several federal agencies seeking an explanation. A spokesperson for the Army’s Criminal Investigation Command, which handles close to 50,000 offenses annually, said the service is adhering to Department of Defense rules regarding crime data and is using a digital crime tracking system linked to the FBI’s database. But the Army declined to say whether its statistics are actually being sent to the FBI, referring that question up the chain of command to the Department of Defense.

In 2014, an internal probe conducted by Department of Defense investigators found that the “DoD is not reporting criminal incident data to the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for inclusion in the annual Uniform Crime Reports.”

ProPublica contacted the Department of Defense for clarification, and shared with a department spokesman a copy of the 2014 reports acknowledging the failure to send data to the FBI.

“We have no additional information at this time,” said Christopher Sherwood, the spokesman.

Federal agencies are hardly the only ones to skip out on reporting hate crimes. An Associated Press investigation last year found at least 2,700 city police and county sheriff’s departments that repeatedly failed to report hate crimes to the FBI.

In the case of the FBI itself, Blasher said the issue is largely technological: Agents have long collected huge amounts of information about alleged hate crimes, but don’t have a digital system to easily input that information to the database, which is administered by staff at an FBI complex in Clarksburg, West Virginia.

Since Blasher began pushing to modernize the FBI’s data systems, the bureau has made some progress. It began compiling some limited hate crimes statistics for 2014 and 2015, though that information didn’t go into the national hate crimes database.

In Washington, lawmakers were surprised to learn about the failure by federal agencies to abide by the law.

“It”s fascinating and very disturbing,” said Representative Don Beyer (D-Virginia), who said he wanted to speak about the matter with the FBI’s government affairs team. He wants to see federal agencies “reporting hate crimes as soon as possible.”

Beyer and other lawmakers have been working in recent years to improve the numbers of local police agencies participating in voluntary hate crime reporting efforts. Bills pending in Congress would give out grants to police forces to upgrade their computer systems; in exchange, the departments would begin uploading hate crime data to the FBI.

Beyer, who is sponsoring the House bill, titled the National Opposition to Hate, Assault, and Threats to Equality Act, said he would consider drafting new legislation to improve hate crimes reporting by federal agencies, or try to build such a provision into the appropriations bill.

“The federal government needs to lead by example. It’s not easy to ask local and state governments to submit their data if these 120 federal agencies aren’t even submitting hate crimes data to the database,” Beyer said.

In the Senate, Democrat Al Franken of Minnesota said the federal agencies need to do better. “I’ve long urged the FBI and the Department of Justice to improve the tracking and reporting of hate crimes by state and local law enforcement agencies,” Franken told ProPublica. “But in order to make sure we understand the full scope of the problem, the federal government must also do its part to ensure that we have accurate and trustworthy data.”

Virginia’s Barbara Comstock, a House Republican who authored a resolution in April urging the “Department of Justice (DOJ) and other federal agencies to work to improve the reporting of hate crimes,” did not respond to requests for comment.

Related Articles:

The FBI’s Crime Data: What Happens When States Don’t Fully Report (#GotBitcoin?)

Citizens Cannot Turn The Police Away If They Are Unhappy With Their Services (#GotBitcoin?)

Have You Broken A Federal Criminal Law Lately? Who Knows? No One Has Been Able To Count Them All!!!

Before Leaving, Sessions Limited Agreements To Fix Police Agencies (#GotBitcoin?)

Mobile Justice App. (#GotBitcoin?)

SMART-POLICING, COMPETITION AND WHY YOU SHOULD CARE (PART I, Video Playlist)

Citizen Surveillance Is Playing A Major Role In Terrorist And Other Criminal Investigations

Your questions and comments are greatly appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.