Should You Find Out If You’re At Risk of Alzheimer’s?

With a simple at-home genetics test, some people are learning they have a higher risk of Alzheimer’s. Can they do anything to prevent the disease? Should You Find Out If You’re At Risk of Alzheimer’s?

When Theresa Braymer can’t remember a word or name, she sometimes second-guesses herself.

Related:

How Sauna Use May Boost Longevity & Prevent Alzheimer’s

Clinical Trials To Combat Alzheimer’s Disease

Everyone has two copies of the apolipoprotein E, or APOE, gene—one inherited from each parent. There are three variants of the gene. The e4 variant is associated with a heightened Alzheimer’s risk.

About 20% of the population has one or two copies of the e4 variant, said Rudy Tanzi, professor of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School and co-director of the McCance Center for Brain Health.

One copy increases your risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease three- to four-fold, according to studies. About 2% of the world’s population has two copies of the e4 variant, which can increase the risk by as much as 14-fold, Dr. Tanzi said.

Ms. Braymer is one of them. Like many people aware of their APOE status, Ms. Braymer learned about it five years ago after taking a genetic test sold online by the company 23andMe. Many consumers are in a quandary when the test reveals the risk of a disease for which there is neither a clear prevention strategy nor a treatment.

A spokesman for 23andMe says customers who buy their health and ancestry kits can receive free additional reports on sensitive health risks, such as the APOE gene if they read through educational material. He says about 70% of customers opt to receive the information.

Facebook , Reddit and other sites have groups for people who test positive for APOE4. Ms. Braymer joined one, ApoE4.Info, in 2014, shortly after it was formed, and now is vice president of its board. The nonprofit group has thousands of members around the world.

There is no advice derived from randomized-controlled trials—the gold standard in medicine—on preventing Alzheimer’s disease. But most doctors agree that regular exercise, adequate sleep and a heart-healthy diet can lower the risk.

“The Healing Self,” which Dr. Tanzi wrote with Deepak Chopra, advocates for protecting the brain by focusing on sleep, exercising, learning things, controlling stress and hypertension, as well as maintaining social interaction and a healthy diet.

Dr. Tanzi said he receives between a dozen and two dozen emails a day from people who took a direct-to-consumer genetic test and tested positive for the APOE4 variant. He tells them the gene doesn’t guarantee that they will get the disease and that many other risk factors can protect or increase one’s risk.

“There are enough people doing these consumer genetic tests that you know that many more are finding out their APOE status than ever before,” Dr. Tanzi said. “The question is, is it useful? If knowing your e4 status is going to stress you out, well, stress is a risk factor.

You have to think about the effect of the stress of knowing.” It’s also important to consider the consequences of family members inadvertently learning they may have the e4 gene variant, too, he noted.

The APOE gene teaches the body how to produce apolipoprotein E, which carries fats, such as cholesterol, from cell to cell. Most people have the APOE3 variant, which conveys no extra risk for Alzheimer’s—or protection against the disease, Dr. Tanzi said.

A small percentage of the population has one copy of the e2 variant of the gene, which can protect against Alzheimer’s disease. The impact of the e4 gene varies greatly by individual. For example, African-Americans and men with the APOE4 gene have less of a risk of developing Alzheimer’s, studies show.

There are 35 other genes that influence one’s Alzheimer’s risk, Dr. Tanzi said. Researchers at the McCance Center for Brain Health are trying to come up with a genetic-risk test that takes into account APOE4 status, as well as other genes that influence the risk of the disease. They also are launching clinical trials on how sleep and exercise affect brain health, and a separate study on meditation.

Experts are split on whether there is any value to knowing your APOE status. The Alzheimer’s Association and the National Society of Genetic Counselors caution against routine genetic testing for Alzheimer’s disease without proper counseling.

A spokesman for the Alzheimer’s Association said such tests have little value because they provide only general information about risk—and because there is no effective treatment for the disease.

Jason Karlawish, a professor of medicine and co-director of the Penn Memory Center at the University of Pennsylvania, has looked at the reactions of more than 3,000 people who have learned their genotype.

“So far there is no significant uptick in psychological harm or acute psychological catastrophic reactions,” Dr. Karlawish said.

His patients’ adult children often ask if he recommends genetic testing. “My standard answer is: Unless you have very particular reason you want to know your genetic risk, it’s not a very valuable test,” he said.

Robert C. Green, a professor of medicine in the division of genetics at Harvard Medical School, says there is a value to knowing your APOE gene status. He has published a series of studies since 1999 randomizing more than 1,000 people into groups where some people receive information on the version of the APOE gene they have.

People who learned they have an increased risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease reported trying to change their lives. They also are more likely to report plans to purchase long-term care insurance.

“Not everything has a pill or medical-prevention plan, but many information-seeking persons can find all sorts of benefits in better understanding their risk of future disease,” Dr. Green said.

Dale Bredesen, a professor in the department of molecular and medical pharmacology at UCLA and founding president of the Buck Institute for Research on Aging, advocates for specific changes.

His protocol—which costs $75 a month—entails getting regular blood tests to track markers such as insulin resistance and inflammation, as well as following a low-carb, high-fat diet, fasting intermittently and taking supplements.

Dr. Bredesen says he has published two small studies and one 100-person study showing that his protocol can reverse cognitive decline in patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease.

But experts pointed out that his studies aren’t randomized controlled ones. Dr. Bredesen said he needs to build up anecdotal evidence to be able to do one. Many members of the ApoeE4.Info group, including Ms. Braymer, said they follow the principles of Dr. Bredesen’s protocol.

David Holtzman, professor and chair of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Mo., says there is no objective data that specific strategies work aside from a 2015 study conducted in Finland that showed that elderly people who were cognitively normal or had a mild impairment maintained or increased their cognitive ability over two years with exercise, cognitive training and vascular-risk monitoring.

“Right now,” Dr. Holtzman said, “if you lead an active, heart-healthy, pro-brain lifestyle, there’s not much that we can tell somebody that they should do differently.”

Share Your Thoughts

Would you take a genetic test and change your life based on its findings? Join the conversation below.

Updated: 12-22-2022

Drugmakers Are Testing Ways To Stop Alzheimer’s Before It Starts

Compounds in final-stage trials at Eli Lilly and Eisai may halt brain protein buildup linked to cognitive decline.

When someone develops high cholesterol, doctors don’t wait until the patient’s arteries are clogged to start treatment. They prescribe cholesterol-lowering drugs while the person is still healthy to prevent plaque buildup and stop heart attacks.

Now some of the world’s biggest drug companies are trying to do something similar for millions of aging baby boomers at risk of Alzheimer’s disease.

In massive final-stage trials under way at Eli Lilly Co. and Eisai Co., researchers plan to test brain-plaque-removing drugs on thousands of healthy adults. The hope is to stave off cognitive decline before it begins, or at least delay it.

The quest for a treatment has been littered with one failure after another. Only in the past two years has a new generation of anti-Alzheimer’s agents started to show hints of slowing the disease’s progress. But even the most promising drugs, including compounds from Eisai and Eli Lilly now under review by the US Food and Drug Administration, slow cognitive decline by only about 30% when given to people who already show symptoms.

That’s because, by the time people develop obvious signs of Alzheimer’s, damage to key brain areas may already be extensive.

Recent brain-scan studies suggest toxic proteins, including one called amyloid that’s the target of most of the new drugs, accumulate in the brain as long as two decades before they lead to dementia.

Neurologists hope that removing amyloid before it has time to cause damage will provide a greater impact for patients. If the concept pans out, healthy adults in their late 50s or early 60s could routinely take blood tests or specialized brain scans that search for buildup of amyloid or tau, another aberrant protein.

If positive, they’d then have to decide whether to go on amyloid-lowering drugs to reduce the odds of developing dementia in the distant future.

“If you wait until people have symptoms, you may not be able to fully prevent the complications,” says Harvard Medical School neurologist Reisa Sperling, who’s leading two of the biggest prevention trials. “Removing the amyloid before people are impaired is the key.”

Sperling’s first big trial, which started in 2014, could produce results next year. Co-sponsored by the National Institute on Aging and Eli Lilly, the almost 1,200-person trial involves testing an amyloid-reducing drug called solanezumab on healthy people age 65 and older with high levels of the brain protein.

Because the drug failed in three unrelated trials by Eli Lilly for treatment of patients who’ve already developed Alzheimer’s, researchers are using a much higher dose in the prevention trial. While not as potent as more recent amyloid-lowering drugs, it largely avoids the brain swelling that’s a side effect of the newer drugs—a potential advantage should it work, Sperling says.

Her more recent trial, started in 2020 and sponsored by Tokyo-based drugmaker Eisai and the National Institute on Aging, is more ambitious. Over four years it’s giving infusions of the company’s lecanemab or a placebo to healthy people as young as 55 with moderate to high amyloid levels. The goal is to start even earlier in life to prevent damage. Eisai is developing lecanemab with partner Biogen Inc.

A third prevention trial involves Eli Lilly’s newer amyloid-lowering drug, donanemab, which is under review at the FDA for accelerated approval as a treatment. The company is betting that just nine monthly doses may be needed to remove amyloid in healthy people, keeping cognitive impairment at bay for years.

In 1906 the German psychiatrist Alois Alzheimer first noticed what turned out to be deposits of amyloid and tau in the brain of a 51-year-old woman who’d died with severe memory loss.

Although the causes of Alzheimer’s remain hotly debated, the correlation between high levels of amyloid and cognitive decline has become increasingly clear in recent years as researchers developed brain-scan technologies that make it possible to measure amyloid levels in the brains of living people.

Astrida Schaeffer, a 59-year-old costume historian in southern Maine, joined the lecanemab prevention trial because she “is absolutely terrified” of getting Alzheimer’s given her family’s extensive history with the disease.

Her grandmother, grandmother’s sister, mother and an aunt all died from Alzheimer’s. Her mother was a high school language teacher who was fluent in five languages before dementia struck, largely taking her ability to speak.

A year ago, after hearing about the lecanemab prevention trial, Schaeffer got an amyloid scan as part of the trial screening and learned she had high levels. Every two weeks she drives several hours round trip to Harvard’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston for trial-related infusions.

Being in the trial “makes me feel less helpless,” Schaeffer says, even though she doesn’t know whether she’s getting the active drug. Despite the hassle of traveling for all the treatments, “if it prevents me from losing my brain, it would be totally worth it,” she says.

Brain-scan studies suggest amyloid builds up slowly for years before symptoms develop, promoting brain inflammation as well as tau, which ultimately leads to cognitive decline. By the time symptoms are obvious, removing massive amounts of the protein does only so much.

In its Phase III trial on 1,800 patients with early Alzheimer’s, Eisai’s lecanemab removed more than 70% of the brain amyloid but slowed the rate of cognitive decline by 27% over 18 months.

Nonetheless, as the best amyloid-lowering treatment trial to date, it’s expected to lead to US approvals for the drug next year—and eventually billions of dollars in sales for Eisai. How noticeable the difference will be for most individual patients is unclear.

With prevention trials, scientists are hoping for a more dramatic impact, says University of Southern California’s Paul Aisen, a neurologist involved in the lecanemab and solanezumab prevention trials. A drug that removes amyloid in healthy people on the verge of cognitive decline might alter their trajectory enough to delay the onset of Alzheimer’s by as much as six years, he estimates.

The lecanemab and solanezumab trials will examine whether the drugs stave off subtle preclinical cognitive changes in people with high amyloid. But Eli Lilly’s donanemab trial aims to prove the drug can prevent disease. The company will wait until more than 400 of a planned 3,300 people progress to mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Then it will count the cases to see if fewer people who took its drug developed cognitive impairment.

While the company doesn’t expect to be able to prevent symptoms in all cases, “we would hope people in [the] donanemab arm would have less progression to symptomatic stages,” says Eli Lilly neurologist Roy Yaari.

For Big Pharma, Alzheimer’s drug development amounts to a massive—but potentially extremely lucrative—bet. But it also raises thorny questions about what the US is able to afford and whether the benefit would be worth the risk. Some 25% of cognitively healthy older adults have amyloid lurking in their brains.

But unlike cheap anti-cholesterol pills, the current amyloid-lowering agents must be injected or infused and are expected to cost $25,000 or more a year. Nobody really knows whether they’ll prevent disease. And the more potent drugs risk triggering brain swelling and brain bleeding.

In a Phase II treatment trial, patients on Eli Lilly’s donanemab saw cognitive decline at a 32% slower rate, but they had a 39% rate of brain swelling or brain bleeding, compared with 8% of those on a placebo. And while lecanemab showed a lower rate of brain swelling, in the “extension” portion of its Phase III treatment trial, two people who took blood thinners while on lecanemab died; Eisai says its drug didn’t cause the deaths.

Given all the uncertainties, critics say the trials are too short and may detect subtle cognitive differences that aren’t clearly meaningful. But the public’s widespread fear of Alzheimer’s devastating memory and cognition losses makes an abandonment of amyloid reduction research unlikely.

“You have potentially millions of people who could be converting into Alzheimer’s” in the coming years, says Eliezer Masliah, director of the neuroscience division at the National Institute on Aging. So something that could delay that by several years “could have a tremendous impact.”

Updated: 1-6-2023

New Alzheimer’s Drug Approved by FDA, Promises To Slow Disease

Eisai and Biogen’s Leqembi is the first drug to show that reducing a protein linked to Alzheimer’s helped patients

U.S. health regulators gave early approval to a new Alzheimer’s drug from Eisai Co. and Biogen Inc., the most promising to date in a new class of medicines that may help slow cognitive decline caused by the disease.

The Food and Drug Administration granted conditional approval to the drug, called lecanemab, based on an early study finding it reduced levels of a sticky protein called amyloid from the brains of people with early-stage Alzheimer’s. The companies will sell it under the brand name Leqembi.

The drug is the first to clearly show in a study that reducing amyloid results in clinical benefits to patients, though doctors say its effects are relatively modest and far from a cure. Use of the drug also raises the risk of side effects, including brain bleeding and swelling.

Still, doctors say its approval is a milestone in the decadeslong search for new Alzheimer’s treatments, and could mark the start of a transformation in treatment in the U.S. of the most common form of dementia and a leading cause of death.

“We’ve been trying for years, decades, and we need the win,” said Marwan Sabbagh, an Alzheimer’s specialist at the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix and a paid consultant to Biogen and other companies. “Now, we have a small win, a modest win, but it’s a win still.”

Roughly six million people in the U.S. are thought to have the disease, and those in the early stages, especially, could start taking an anti-amyloid drug in the years ahead. Eli Lilly & Co.’s donanemab, a similar anti-amyloid drug, is up for early approval sometime early this year.

Japan’s Eisai, which has led the drug’s development, has said it plans to seek full approval based on a recently completed study showing Leqembi slowed disease progression by 27% compared with a placebo.

Eisai estimates that the drug delayed patients’ disease getting worse by about five months over 1.5 years of treatment.

At least in the near-term, however, Leqembi and other anti-amyloid drugs will be out of reach for most patients because of a Medicare decision in April 2022 to deny routine coverage of such drugs.

Under current Medicare rules, patients must be enrolled in approved clinical trials to get the drug paid for. No such studies are ongoing or planned, according to an Eisai spokeswoman.

Medicare officials can reconsider their coverage decision, but the process could take as long as six to nine months.

Researchers have struggled for decades to find medicines that slow Alzheimer’s, which slowly robs people of their memories and ability to carry out everyday tasks. Current treatments can alleviate symptoms of the disease, but don’t attack its underlying causes.

The FDA granted early approval to the anti-amyloid drug Aduhelm in June 2021, a controversial decision because of the drug’s mixed results in two large studies that were mistakenly ended early by Biogen, which also co-developed that drug with Eisai.

Eisai’s study of Leqembi, by contrast, was a well-run study that showed benefits across nearly all measures that were analyzed, said David Knopman, a Mayo Clinic neurologist who was critical of the FDA’s approval of Aduhelm.

Whereas the Aduhelm studies weren’t reported in a peer-reviewed scientific journal until well after its approval, Eisai’s Leqembi study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine weeks after the initial results were announced in a news release.

“These are clean, albeit small benefits,” Dr. Knopman said.

Last week, an investigation by House Democrats found that the FDA inappropriately collaborated with Biogen officials before approving Aduhelm by holding an atypical number of meetings with the company and working closely together on a briefing document prepared for outside advisers.

The investigation also found that Biogen priced the drug at $56,000 annually to maximize revenue despite internal analyses predicting pushback from patients and payers. Biogen later cut the price in half.

In addition to uncertain insurance coverage, anti-amyloid drugs carry the risk of side effects and can be burdensome to take.

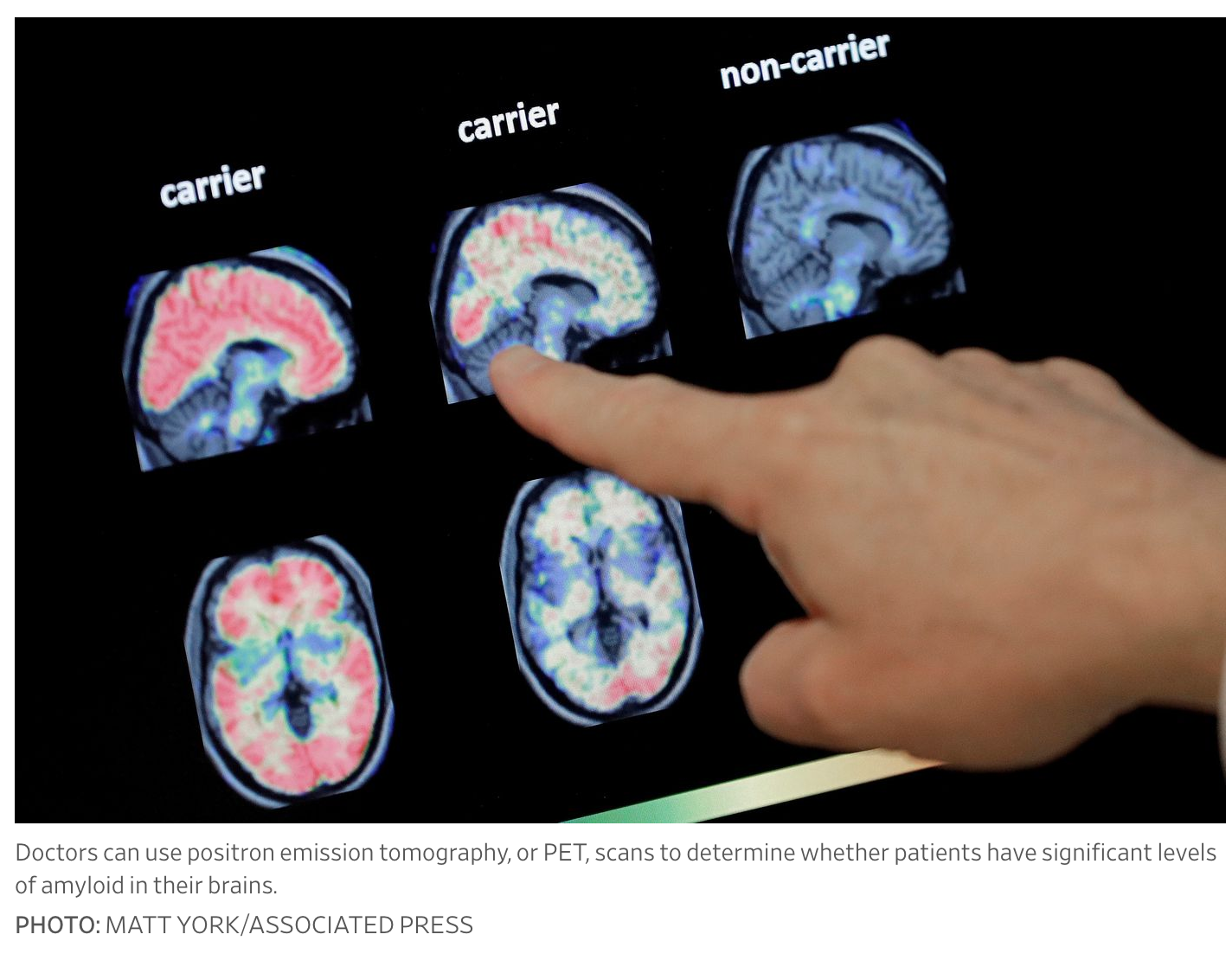

Leqembi requires twice-monthly drug infusions, typically given at an outpatient clinic or hospital. Doctors will have to confirm that patients have significant levels of amyloid in their brains before treatment, which is most commonly measured using positron emission tomography, or PET, scans.

Leqembi and other anti-amyloid drugs can cause brain swelling and bleeding, particularly in the first several months of treatment. The side effect is sometimes known by the acronym ARIA, short for “amyloid-related imaging abnormalities.”

In the largest study of Leqembi, 17.3% of patients taking the drug had brain bleeds, compared with 9% of those who received placebos. Brain swelling occurred in 12.6% of Leqembi patients, versus 1.7% of placebo patients.

Doctors say that with proper monitoring, the side effects are manageable and that most patients don’t experience any negative symptoms such as headaches or dizziness. If the bleeding or swelling is detected using magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI, scans, treatment can be paused until the patient recovers.

However, the risk of bleeding can be especially dangerous for people taking blood thinners, a common treatment for heart disease. Two patients in the Leqembi study died after taking the drug with blood thinners, Eisai reported at a medical conference in November.

In December, Science reported that a third patient in the study died after suffering from severe brain swelling and bleeding. “The information provided to Eisai to date does not indicate that ARIA occurred or that it was suspected to be linked to the death,” an Eisai spokeswoman said.

“The long term consequences, fortunately, are extremely rare,” said Dr. Knopman. Still, some doctors, including Dr. Knopman, say that patients shouldn’t take blood thinners while on anti-amyloid treatment.

Analysts expect anti-amyloid drugs to eventually generate billions of dollars in annual sales. Medicare reimbursement will probably not be in place until the end of 2023, said Michael Yee, a Jefferies biotech analyst.

“This is going to take a year to get ramped up and build the market,” said Mr. Yee.

Leqembi is projected to reach $351 million in 2024 and to grow to $2.2 billion in 2027, according to analysts polled by FactSet.

Lilly’s donanemab is forecast to have $1.05 billion in 2024 sales, and to reach $2.1 billion in 2027, according to FactSet.

Related Articles:

Carolyn’s Natural Organic Handmade Soap

Men’s Health Checklist For Every Age

A Bedside Lamp Designed To Help You Sleep Better (#GotBitcoin?)

Wellness Shots Deliver A Real Kick (#GotBitcoin?)

Most Doctors Don’t Know About This Breakthrough AFIB Technique (#GotBitcoin?)

We Now Live In A World With Customized Bar Soaps, Lotions And Shampoos (#GotBitcoin?)

Good Company: Purearth’s High-Altitude, Himalayan-Born Skincare (#GotBitcoin?)

At-Home Light Therapy Beauty Mask Treatments (#GotBitcoin?)

Hate Buying Household Cleaning Supplies? There’s A Pill For That

The Iodine Deficiency Epidemic — How To Reverse It For Your Health

Dollar Stores Feed More Americans Than Whole Foods (#GotBitcoin?)

Consumer’s Appetite For Organic, Antibiotic / Hormone-Free Food Outstrips Supply (#GotBitcoin?)

Food Companies Get Until 2022 To Label GMOs (#GotBitcoin?)

Food, The Gut’s Microbiome And The FDA’s Regulatory Framework

Food Regulators To Share Oversight of Cell-Based Meat (#GotBitcoin)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.