Chinese Scientist Claims World’s First Genetically Modified Babies

A Chinese scientist claims to have produced the world’s first genetically modified babies, stirring alarm among doctors who warn such experiments using nascent DNA-editing technology pose too many health and ethical risks. Chinese Scientist Claims World’s First Genetically Modified Babies

Scientific community expresses alarm, warning that experiments using nascent DNA-editing technology pose too many risks.

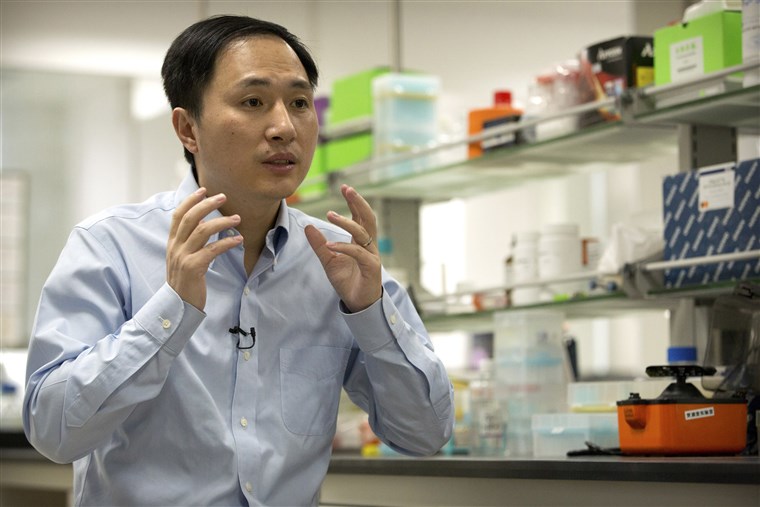

He Jiankui, an associate professor at Shenzhen-based Southern University of Science and Technology, said that he oversaw the pregnancy and the birth this month of twin girls designed to resist the HIV infection. They were the offspring of a healthy mother and a father infected with the deadly virus. Dr. He said he deactivated a gene that researchers believe enables the virus to invade the body’s cells.

The research hasn’t been published or vetted by other scientific experts, nor could Dr. He’s claims be independently verified. The experiment wouldn’t be permitted in the U.S.

Scientists and doctors in China and abroad swiftly rebuked Dr. He after the Associated Press first reported the news of the births on Monday. The global scientific community has previously voiced concern that China is racing ahead with gene-editing experiments without adequate regulation or oversight.

Gene-editing tools such as Crispr-Cas9, which Dr. He said he used, are cheap, easy-to-use and powerful. They hold great promise to treat intractable diseases by rewriting the building blocks of life. But experts say they are not foolproof and that editing one gene may unintentionally set off changes in another. China is the only country known to have tested Crispr on humans, mostly to treat adult patients in advanced stages of cancer. Crispr was pioneered in the West in 2012.

Editing so-called germ cells—the genes of sperm, eggs and embryos—is even more controversial because any changes would pass on to future generations, giving a tiny blip potentially far-reaching consequences. American and Chinese scientists have used Crispr to alter embryos in a laboratory for research. But until Monday no one has been known to have implanted them into a woman’s womb.

“We need to be incredibly careful as it affects not just a certain group of cells, but whole generations,” said Lap-Chee Tsui, the president of the Academy of Sciences of Hong Kong.

As word of the births spread online in China, more than 100 doctors signed a letter circulating on social media saying they deemed the research unethical and dangerous.

The U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine said such trials should be allowed “only for compelling medical reasons in the absence of reasonable alternatives, and with maximum transparency and strict oversight.” It said it was unclear Dr. He’s experiments met those criteria.

Dr. He’s employer, the Southern University of Science and Technology, condemned the research. Dr. He took a leave of absence in February, according to a university statement, and conducted the experiment in his personal capacity at HarMoniCare Women & Children’s Hospital in Shenzhen, with which Southern University isn’t affiliated. The experiment “is in serious violation of academic ethics and academic standards,” the statement said.

Dr. He said he had proceeded with the blessing of HarMoniCare’s ethics review board, the only requirement necessary in China. In the U.S., federal clearance is also needed for such experiments and experts say it wouldn’t be permitted. HarMoniCare said it was investigating the authenticity of the approval document, posted on a Chinese registry of clinical trials and dated March 2017.

Shenzhen’s health authority said HarMoniCare had failed to register its ethics committee with the authority, disqualifying it from approving any medical research.

Dr. He didn’t immediately respond to the university and health authority claims but the scientist said in a brief email exchange: “I understand it is easier to not be the first, but I can take any criticism because my pain will not equal the pain of families struggling with genetic disease.”

A spokesman for Dr. He declined to identify the twins’ parents or make them available for an interview.

Dr. He is scheduled this week to speak at an international summit organized by the national science academies of Hong Kong, the U.S. and the U.K. The summit, which begins Tuesday, aims to help build an international consensus around the use of gene-editing tools.

In five videos posted Monday on YouTube, Dr. He details the experiment and outlines his reasons for engineering the twins. “If we can help these families protect their children, it is inhuman of us not to,” he says in one video.

Eight couples qualified for Dr. He’s research, according to the spokesman, of which five women were implanted with 13 edited embryos. Of them, only one pregnancy—with the twin girls—carried to term. The girls were born at a different hospital to the one that signed-off on Dr. He’s research, the spokesman said.

One of the babies was born without both copies of the gene, known as CCR5, while the other still had one copy of the gene. It is unclear if either baby is resistant to HIV. Dr. He plans on monitoring them at least until they turn 18, and perhaps longer with their consent.

Knocking out the CCR5 gene “is not entirely benign because it increases the risks associated with West Nile virus infection and influenza,” said Bruce Walker, director of the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard, who is involved in a long-running effort studying people who have HIV and are able to control the virus without antiretroviral treatment. “It is not without consequences.”

Dr. He is a staff member of Southern University of Science and Technology’s biology department. The scientist received a Ph.D. from Rice University in 2010 and performed postdoctoral research at Stanford University. Dr. He is a member of China’s “Thousand Talents Program,” a Beijing-led initiative to reward skilled Chinese researchers who returned from overseas, according to the website.

Updated 1-21-2019

China Takes Steps Against Scientist Who Engineered Gene-Edited Babies

He Jiankui will be transferred to authorities; officials say those involved in the experiment will be ‘severely dealt with.’.

Chinese authorities investigating a scientist who claimed to have engineered the world’s first gene-edited babies accused him of violating national laws and forging documents needed to proceed with the experiment, state media reported Monday.

Officials told the Xinhua News Agency that the scientist, Shenzhen-based He Jiankui, “will be transferred to public security authorities,” and the people involved in the experiment “severely dealt with according to the law.” Xinhua didn’t elaborate.

A spokesman for Dr. He didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

The comments marked the first time Chinese authorities alluded to the possible fate of the scientist. It was also the first time China acknowledged the controversial births.

Dr. He stunned the world in November with the announcement he had engineered twin girls—offspring of a healthy mother and an HIV-positive father—to be resistant to HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, using a nascent gene-editing technology called Crispr-Cas9.

The revelation drew rebukes from the global scientific community, including the inventors of the gene-editing technology. Crispr—while powerful—isn’t foolproof. Editing the genes of embryos is more contentious than editing those of terminally ill patients because any changes would pass on to future generations. Unintended consequences might not surface for several years, meaning a tiny blip could have far-reaching consequences.

Dr. He has publicly defended his actions, saying his intention is to protect the children of HIV-positive individuals from the disease. Many scientists have argued HIV-positive couples can produce healthy children. The U.S. National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine has said editing embryos’ genes should be allowed “only for compelling medical reasons in the absence of reasonable alternatives, and with maximum transparency and strict oversight.”

An initial probe revealed Dr. He’s experiment didn’t meet those criteria, according to Xinhua. Eight couples were involved in the research, of which one woman implanted with gene-edited embryos carried to term, bearing twins, and a second pregnancy occurred. One couple dropped out, while the five others didn’t get pregnant, Xinhua reported Monday.

Officials said implanting such embryos is illegal in China, and alleged Dr. He forged an ethics review to proceed with the experiment. Such reviews are the only paperwork Chinese doctors need to open experimental trials. Doctors in the U.S. would also need federal permission.

In a statement Monday, China’s science ministry said it “resolutely opposed” the experiment. It said it would work to “improve relevant laws and regulations and improve the scientific research ethics review system.”

Dr. He’s employer, Shenzhen-based Southern University of Science and Technology, said Monday it was firing him. The school previously denied knowledge of the experiment, saying Dr. He conducted it in his individual capacity. Dr. He—a staff member of the university’s biology department—has acknowledged the school was unaware.

Authorities in Guangdong Province, where Shenzhen is located, told Xinhua they were monitoring the gene-edited infants as well as the second woman who is yet to give birth. Authorities couldn’t immediately be reached for comment. Xinhua said Dr. He acted in “the pursuit of personal fame” adding his “behavior is a serious breach of ethics and scientific integrity, a serious violation of state regulations.”

Updated: 5-12-2019

How a Chinese Scientist Broke the Rules to Create the First Gene-Edited Babies

Dr. He Jiankui, seeking glory for his nation and justice for HIV-positive parents, kept his experiment secret, ignored peers’ warnings and faked a test.

Two sisters entered the world prematurely one October night last year by emergency caesarean section. Staff at the Chinese hospital swaddled them in white, laying them in incubators.

The twins had a secret almost no one at the hospital knew. One man who did know was there, waiting—a U.S.-educated researcher, Dr. He Jiankui, who had flown into town to see them.

The twins were his creations, the world’s first known gene-edited human babies. He had worked toward this for two years, altering their genes as embryos to try making them resistant to their father’s HIV infection. Dr. He (pronounced “huh”) gave them pseudonyms, Lulu and Nana.

“I’m 70% happy and 30% uncertainty,” he said in an English voice message to a colleague that night.

His unease proved prescient. When the news broke, peers in China and abroad condemned him for manipulating life’s building blocks using a relatively untested gene-editing tool.

Gene-editing trials involving terminally-ill adult humans are ongoing. But tinkering with embryos is more controversial because changes in them will pass to future generations, meaning a tiny blip could have far-reaching consequences.

At a Nov. 28 Hong Kong summit of leading geneticists, participants bombarded Dr. He with questions about his methods and ethics.

A day later, Chinese officials declared his experiment illegal. Authorities in January detained him after an initial probe alleged he forged an approval document and acted in “pursuit of personal fame.”

He hasn’t been publicly heard from since November. Attempts to reach Dr. He, who appears to remain in custody, weren’t successful. His wife declined to comment through a person close to him. It isn’t clear if Dr. He has legal representation.

Dr. He, now 35, left behind the mystery of what motivated him to defy his field’s widely held ethical principles, how he carried out his trial in stealth, why nobody stopped him—and why he was so stunned by the backlash.

A picture of just how far the scientist went to fulfill his dream emerges from a Wall Street Journal examination of his notes, emails, voice memos, clinical-trial documents and from interviews with people who knew him, some of whom were familiar with his trial, and the birth of the babies.

His drive and interests were hardly secret: A small group of highly regarded Western peers watched from the sidelines, offering advice and urging caution. Dr. He held the scientist’s ambition to make history, people who know him said. He also wanted to address what he saw as an injustice in China against families with HIV-positive parents, who are barred from fertility treatments.

The scientist, who hadn’t run a human trial before, didn’t tell the doctor who implanted the twins’ mother that their genes were edited, and he kept the nature of his experiment secret from the hospital where it took place, said people familiar with the details of the trial. He faked the father’s blood test to avoid detection of his HIV, according to these people. He succumbed to the hopes of his patients, against his own medical judgement, and impregnated women eager to conceive.

A deeply patriotic man, Dr. He had expected plaudits from Beijing for helping in its goal of making China a force in genetic science, people who know him said. “He always spoke in a way as though he wanted to do good for the sake of his nation,” said Stanford University physician and neurobiologist William Hurlbut, who knows Dr. He but says the researcher didn’t tell him of implanting edited genes. “What’s so ironic is that he will be punished badly.”

Dr. He ignored Western scientists’ warnings that implanting edited embryos risked flouting his field’s ethical norms. None appear to have gone beyond giving warnings.

Rice University biochemical and genetic-engineering professor Michael Deem appears in a video of a meeting with parents who volunteered for the trial, in videos the Journal viewed. Dr. Deem, the Chinese scientist’s former doctoral adviser at Rice, was listed as a co-author of a research paper on the twins’ birth.

A lawyer for Dr. Deem said his client commented on Dr. He’s research but didn’t conduct it and that Dr. Deem had asked that his name be retracted from the paper.

Rice is investigating Dr. Deem’s role and declined to comment. Stanford, where Dr. He also studied, said it concluded its professors weren’t involved in his research.

“Everybody who knew anything should quit pointing fingers and come forward and say what are we going to do now—why we felt there was good and bad in this and how no one seemed to know how to proceed,” said Dr. Hurlbut, who said he began suspecting the Chinese researcher was planning such an experiment as their conversations deepened over many months.

Authorities have kept the location of Dr. He’s experiment secret. China’s Ministry of Science and Technology and a local agency investigating Dr. He didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Gene ethics

It is illegal to implant a genetically-modified human embryo in much of the Western world. The U.S. forbids the Food and Drug Administration, whose sign-off is needed for such an experiment, from considering it. China doesn’t have a law, but a 2003 guideline says “genetic manipulation of human gametes, zygotes and embryos for reproductive purposes is prohibited,” without outlining penalties.

A new gene-editing tool named Crispr-Cas9, which holds the promise of new disease treatments, has made ethics questions more urgent. The tool acts like molecular scissors that can target specific genes, cutting and splicing them to prevent or cure diseases.

One broadly held view is that it is too early to use Crispr on the human “germ line”—genes of sperm, eggs and embryos—because changes will pass on for generations and present the specter of unintended consequences to the human race. Lab research has shown Crispr-Cas9 can edit genes other than the ones intended. This means it could disrupt other genes, impairing functions or predisposing people to infections.

The latest international guideline came in a 2017 report from the U.S. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine, and stood at odds with existing legislation in the West. It didn’t call for a ban on implanting edited embryos, saying it should be done “only for compelling medical reasons in the absence of reasonable alternatives, and with maximum transparency and strict oversight.”

Some scientists objected to Dr. He’s trial saying HIV protection wasn’t an unmet need—a fertility treatment can wash the virus off sperm to reduce transmission risk. Dr. He held that it was an unmet need among China’s HIV-positive parents who, banned from fertility clinics, didn’t have that option. He also held that gene editing could make offspring resistant for life to HIV, not just a parent’s infection.

“You could see that people in the West were totally outraged because you never need that here,” said Stanford biophysicist Stephen Quake, in whose lab Dr. He once worked. “But I can see why there may be a different view in China of what he did and a justification for it.”

The son of rice farmers, Dr. He graduated with a physics undergraduate degree in China and a Ph.D. from Rice, then switched to biology. He forged ties with Dr. Deem, a physicist who moved into biochemical engineering, and they published papers together. In 2010, he took a postdoctoral position in Dr. Quake’s Stanford lab.

He returned to China as a biology professor at the Southern University of Science and Technology. In 2012, he founded a gene-sequencing company, Direct Genomics, enlisting to its advisory board influential scientists including University of Massachusetts molecular biologist Craig Mello, a 2006 Nobel laureate.

Dr. He turned his attention to Crispr-Cas9, invented in 2012. In 2015, a group of Chinese researchers provoked a firestorm after using it to edit “nonviable” human embryos that can’t result in pregnancies. American scientists called it irresponsible to use the still-unproven tool on human embryos.

But it was a heady time for scientists in China, with President Xi Jinping urging them to “innovate, innovate, innovate!” and the Communist Party laying out goals to be a technological world player.

Dr. He began using Crispr in 2016 to edit the genes of mice, monkeys and nonviable human embryos. That fall, visiting Dr. Quake, he said: “I want to create the first gene-edited humans,” Dr. Quake recalled.

“You must do it carefully,” Dr. Quake said he warned him. “Otherwise, it will ruin your scientific career.”

In a 2017 meeting with Dr. He, Stanford’s Dr. Hurlbut said, “one of the first things he said to me when he sat down was, ‘The people against embryo research in the U.S., that’s just a fringe, just a fraction, right?’ ”

The American responded: “Not really, JK,” addressing Dr. He by the initials he uses in emails. “America’s pretty evenly divided on that issue.”

The U.S. government is barred from funding work that involves endangering, destroying, or creating embryos for research, Dr. Hurlbut told Dr. He. Such concern about something that hadn’t yet been born was hard to fathom for Dr. He, who has two young daughters.

Dr. Hurlbut said the Chinese scientist expressed incredulity, asking: “You mean something as small as this is as valuable as my 2-year-old daughter?” and pressing his forefinger against his thumb. Dr. Hurlbut responded: “That’s the way your little daughter’s life began.”

Dr. He was investigating editing a gene that can offer protection from familial hypercholesterolemia, a rare cholesterol-related disease that can cause broken bones in children. He changed his mind after visiting a village where he saw HIV-positive families facing discrimination, people close to him say. Children born to infected individuals weren’t able to attend regular schools. He saw a gene-editing trial as a way to use science against that injustice.

His team found 22 couples eager to conceive, some with fertility issues. The men were HIV-positive; the women weren’t. Visiting their homes, Dr. He’s team used PowerPoint slides to show how they would develop the couples’ embryos and edit genes to cause a mutation that research showed made it possible to resist HIV. The embryos would be implanted in the mothers.

Some slides noted potential risks, such as unintended consequences. Others showed a woman saying: “I want a child.”

In the slides’ background was etched the logo of the Southern University of Science and Technology, which later denied knowing about the experiment. The presentation said the project was funded by a grant from the country’s Ministry of Science and Technology, which later denied knowledge of the trial.

Eight selected couples met Dr. He, two at a time, starting in June 2017. A postdoctoral student did most of the talking, videos of the meetings show. Rice’s Dr. Deem is present in one of the videos, a silent observer. Dr. Deem’s lawyer declined to comment on his presence, saying his client didn’t conduct the informed-consent process.

By September 2017, all eight couples had enrolled, and Dr. He felt he had no time to waste, people close to the scientist say. Scientists at Oregon Health & Science University had just announced they used Crispr to correct a heart condition in viable embryos that they then destroyed.

The Americans weren’t condemned as the Chinese researchers were in 2015, Dr. He observed at the time. “If it’s not me,” he later recalled in a promotional video, “it’s someone else.”

Subterfuge

Dr. He’s team started implanting embryos in early 2018, according to a person familiar with the trial. He had planned to treat participants at a Shenzhen hospital whose ethics committee he said had approved his trial—the permission he needed under Chinese regulations. The hospital’s parent company later said the approval document was forged.

The couples selected didn’t live there, so Dr. He hired an embryologist at a different hospital to edit their embryos. The embryologist kept the true nature of Dr. He’s trial secret from his own hospital and the fertility doctor who would implant the embryos, according to the person familiar with the trial.

Only one of the embryos that became Lulu and Nana was successfully edited, but the couple wanted both implanted anyway, although they knew one twin probably wouldn’t have HIV resistance. When the hospital needed the father’s blood sample, Dr. He’s team produced an HIV-negative man to give blood, the person familiar with the trial said.

In April 2018, in an email exchange viewed by the Journal, Dr. He wrote Dr. Mello: “Good News! The women is pregnant, the genome editing success!”

Dr. Mello wrote back: “I’m glad for you, but I’d rather not be kept in the loop on this…I just don’t see why you are doing this,” saying he couldn’t understand using Crispr for HIV when existing methods reduced transmission.

Dr. Mello referred inquiries to a UMass spokeswoman, who said that he believed Dr. He in the email was referring to an experiment in China and that Dr. Mello didn’t know Dr. He was doing it himself.

Among other mentors Dr. He consulted was Stanford’s Dr. Quake, who said his former student told him he had the requisite approval from a Chinese hospital’s ethics committee, known in the U.S. as an institutional review board, or IRB. “If someone’s doing IRB-approved research, you’re saying, OK, they’ve looked at it,” Dr. Quake said. “You’re not in a position to judge whether it’s right or wrong…What are you going to do? Who are you going to call up?”

At times, Dr. He questioned whether he had been too emotional in choosing to target HIV, and should have stuck with familial hypercholesterolemia or picked a different disease, people he consulted say.

Before implanting embryos in more women, Dr. He had wanted to wait for the twins’ birth and data on them. But other participants pressured him to let them conceive. He warned one couple that data from the twins could show editing genes wasn’t as safe as he had hoped and that waiting might shield them and their unborn baby from potential harm. He made them sign a document, reviewed by the Journal, acknowledging his advice. His team implanted the couple, bringing the total to 13 embryos in five women, according to the person familiar with the trial.

One October evening, the twins’ expectant father called a member of Dr. He’s lab to say his wife was going into labor. Dr. He raced to Shenzhen airport, postdoctoral students in tow, and flew north.

A photo taken the next day shows a smiling Dr. He. An umbilical-cord tissue analysis found one twin’s DNA was successfully edited. The other was partially edited, making it unclear it would resist HIV.

The hospital remained unaware the twins were special until after the births, said the person familiar with the trial. Its ethics committee for stem-cell research subsequently issued a document saying it had agreed to participate in the trial, according to a text exchange between Dr. He and the person, who added that another person on the scientist’s team said the hospital backdated its approval to appear as though it had known all along.

In November, Dr. He submitted preliminary data on the twins to the scientific journal Nature, the paper on which Rice’s Dr. Deem was listed as a co-author. Nature declined to publish it after news of the births broke. A Nature spokeswoman said it doesn’t comment on its review process.

After a Direct Genomics board meeting in November, Dr. He approached Dr. Mello, who remained an adviser, according to a voice message the Chinese scientist sent a colleague. Dr. He said Dr. Mello told him that if he could find data showing healthy children born to HIV-infected parents were at great risk of contracting the virus later, it might help scientists embrace the idea of viral resistance, Dr. He noted in his voice note, heard by the Journal, adding that his team “must immediately find those data.”

On Nov. 22, he emailed Dr. Mello thanking him for his advice, saying: “Again, I won’t tell people that you know what is happening here.”

Dr. Mello says the in-person conversation didn’t take place, said the UMass spokeswoman, quoting him as saying: “I cannot explain why he acknowledges me for this” over email.

Dr. He initially planned his announcement for January after the twins were due. The premature births changed that. He was due to speak at the Hong Kong gene-editing conference about nonviable embryos. He decided to announce the births, according to people close to him.

Four days before the conference, he emailed Jennifer Doudna, a University of California, Berkeley, biochemist who co-invented Crispr-Cas9 and was on the organizing committee. “He was hellbent at announcing his work at the conference,” said Dr. Doudna, who said she hadn’t known about his work on human babies and was “very upset.”

He decided against announcing, but, as he headed for the summit, a news report broke about the births. At a dinner that evening, Dr. Doudna said, scientists asked Dr. He: “Do you understand that people are going to be very upset?”

“He seemed surprised,” she said, “to hear that people were concerned.”

In a 20-minute summit presentation, Dr. He detailed his Crispr research. Scientists, bioethicists and regulatory experts demanded: What were his methods? How did he recruit patients? Did he tell them of the risks?

“I don’t know how to answer these questions,” Dr. He said at one point, voice quivering.

Back in Shenzhen, he was on the phone with confidants including Benjamin Hurlbut, an Arizona State University bioethicist and son of Stanford’s Dr. Hurlbut. “He was trying to make sense of what went wrong in what he saw as a virtuous, important contribution to scientific progress,” Dr. Hurlbut said, adding that Dr. He told him: “I could’ve done it better.”

He told Dr. Hurlbut he remained hopeful his nation would stand by him.

In January, Chinese investigators released their initial findings, promising stiff penalties. Dr. He’s university fired him.

In letters addressed to the judiciary and reviewed by the Journal, three of his volunteers said they enrolled aware of the risks. “We wanted to contribute to science and society,” one wrote, “and, at the same time, wanted a healthy baby.”

In March, Chinese officials drafted stricter rules for human-gene editing. The World Health Organization is drafting global guidelines.

“Of course, he made his own choices. But he was a product of his environment,” Arizona University’s Dr. Hurlbut said of Dr. He. “The narrative of a rogue scientist excuses the rest of science from having played a role. That’s just not true,” he added.

Chinese authorities have given no information about Lulu and Nana. A second couple from Dr. He’s trial is awaiting birth of their gene-edited child—the couple he had warned against implanting.

Updated: 12-30-2019

Chinese Scientist Who Gene-Edited Babies Is Sent To Prison

A Chinese court convicted He Jiankui on charges of illegally practicing medicine, sentencing him to three years in prison.

The scientist who created the world’s first known genetically modified babies, stunning the global scientific community, has been sentenced by a Chinese court to three years in prison, state media reported.

He Jiankui said in November last year he had engineered twin girls—offspring of a healthy mother and an HIV-positive father—to be resistant to HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, using a nascent gene-editing technology called Crispr-Cas9.

China was able to race ahead of the U.S. on testing gene-editing technology because it had few regulatory hurdles to human trials, while the U.S. has stringent rules.

But Dr. He’s revelation drew immediate condemnation from bioethicists and fellow scientists in China and beyond, including the inventors of the gene-editing technology. Chinese authorities said last January they were investigating Dr. He, and he was fired from his post as an associate professor at Southern University of Science and Technology, based in the southern city of Shenzhen.

On Monday, a Shenzhen court convicted Dr. He and two accomplices on charges of illegally practicing medicine related to carrying out human-embryo gene-editing intended for reproduction, the official Xinhua News Agency reported.

The court said Dr. He hoped to profit by commercializing the technology and that he forged documents and concealed the true nature of the procedures from both the patients he recruited and doctors who performed them, according to Xinhua. The report said all three defendants pleaded guilty.

“In order to pursue fame and profit, they deliberately violated the relevant national regulations, and crossed the bottom lines of scientific and medical ethics,” the court said, according to the report.

Dr. He also received a lifetime ban from working in the field of reproductive life sciences and from applying for related research grants, Xinhua said, citing local health and science authorities.

Dr. He couldn’t be reached for comment, and the identity of his lawyer isn’t known. A former spokesman for Dr. He didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

Gene editing of embryos is taking place for research purposes in countries including the U.S. and the U.K., in lab settings. Scientists have said they are unaware of any current efforts involving gene editing of embryos for implantation and birth. But policy experts and scientists expect it will happen.

“Some scientists have announced their wish to edit the genome of embryos and bring them to term,” Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, World Health Organization’s Director-General, told the WHO expert advisory committee examining governance and oversight of human genome editing, earlier this year. WHO has announced plans for a global registry to list clinical trials involving human genome editing as a way to track research.

“WHO recommends that regulatory authorities in all countries should not allow any further work in this area until its implications have been properly considered,” said a spokesperson for WHO.

Editing the genes of embryos is considered more contentious than editing those of terminally ill patients because any changes would pass on to future generations. Unintended consequences might not surface for several years, meaning a tiny blip could have far-reaching effects.

In what turned out to be one of his last public appearances in November last year, the Chinese scientist sprang another surprise at a scientific conference in Hong Kong, announcing a second woman was pregnant with a gene-edited baby.

Monday’s Xinhua report confirmed the birth of a third gene-edited baby from a second pregnancy but provided no other details. Previous state-media reports had said the newborn twins and people involved in the second pregnancy would be monitored by government health departments.

Dr. He, the son of rice farmers, graduated with a physics undergraduate degree in China and got a doctorate from Rice University, before switching to studying biology.

As earlier reported by The Wall Street Journal, people who know Dr. He have said he wanted to make history and address what he saw as an injustice in China against HIV-positive people, who are barred from getting fertility treatments. They said Dr. He had expected plaudits from Beijing for helping in its goal of making China a force in genetic science.

In much of the Western world, it is illegal to implant a genetically modified human embryo. The U.S. forbids the Food and Drug Administration, whose signoff is needed for such an experiment, from considering it. China doesn’t have a law, and although a 2003 guideline prohibited the genetic manipulation of human embryos, it didn’t outline penalties. In February, China’s National Health Commission drafted new rules governing “high-risk” biotechnology, including gene-editing, that would introduce criminal charges and lifetime research bans if breached, but they have yet to come into effect.

Victor Dzau, president of the U.S. National Academy of Medicine, one of the conveners earlier this year of the International Commission on the Clinical Use of Human Germline Genome Editing, said the jail sentence for Dr. He and his colleagues will “have a big effect globally on all scientists.” Not all governments have policies regarding the editing and implantation of human embryos, he said. “The scientists don’t know how their government will respond,” said Dr. Dzau.

The commission is attempting to create suggested guidelines and advice for scientists, clinicians and governments regarding human embryo gene editing.

“In the United States, everybody realizes this is something we should not do at this time. It is irresponsible until we have good guidance,” he said.

Some countries, Dr. Dzau added, may eventually conclude that human genome editing in embryos is acceptable under certain circumstances such as preventing lethal disease, and move forward. “Then it is up to each country,” he said. “Some decisions may be culture-dependent.”

Kiran Musunuru, an associate professor of cardiovascular medicine and genetics at the University of Pennsylvania and the author of a recent book about Crispr and the gene-edited babies, said the jail sentence is likely to have a deterrent effect on scientists in China. “This is a signal that China is serious about restricting this sort of research and clamping down on rogue actors like He,” he said. “What happens behind closed doors is hard to know, but outwardly at least, they have taken a serious stance.”

Dr. Musunuru said that he believes gene editing involving patients with life-threatening diseases will continue, and so will clinical trials in such cases, which have a clear regulatory framework in the U.S.

Jennifer Doudna, a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, and one of the Crispr inventors, said in addition to the ethical problems involved in Dr. He’s experiment, there are also scientific ones.

“We don’t have the ability to control the editing outcomes in a way that would be safe in embryos right now,” said Dr. Doudna.

Regarding the specific gene-editing changes made in the embryos, “We don’t really know what was done,” she said. “From the data presented, it looks as though the edits made were not the ones that were intended. It is very difficult to know how those edits will in fact affect the health outcomes of these kids.”

Scientists are uncertain about how the children will be monitored, their health-care needs, if the experiment harmed them, or what will happen to them in the future.

Dr. Doudna said she supports efforts by the international scientific community to discuss not only the technology but the social, ethical and technical challenges.

“To me, the big question is not will this ever be done again. I think the answer is yes. The question is when, and the question is how.”

Related Articles:

I Downloaded My DNA This Week (#GotBitcoin?)

Deformities Alarm Scientists Racing to Rewrite Animal DNA (#GotBitcoin?)

Crispr, Eugenics And “Three Generations Of Imbeciles Is Enough.” (#GotBitcoin?)

Deformities Alarm Scientists Racing to Rewrite Animal DNA (#GotBitcoin?)

Meet The Scientists Bringing Extinct Species Back From The Dead (#GotBitcoin?)

Our Facebook Page

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.