Smart Wall Street Money Builds Homes Only To Rent Them Out (#GotBitcoin)

Companies that once gobbled up foreclosed suburban homes are now acquiring new ones for the rental market. Smart Wall Street Money Builds Homes Only To Rent Them Out (#GotBitcoin)

Millennials aren’t the only ones having a hard time finding houses to buy. So is Wall Street.

A home under construction last month in Herndon, Va. Home prices in Fairfax County, Virginia’s most populous jurisdiction, have more than doubled since 2000, according to the Northern Virginia Association of Realtors.

A shortage of houses in the entry-level price range where first-time buyers and big rental-home companies both shop is prompting some institutional landlords to start building new ones themselves.

Related:

Emergency Rental Assistance Program

Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads Throughout World (#GotBitcoin)

Home Flippers Pulled Out of U.S. Housing Market As Prices Surged

Housing Insecurity Is Now A Concern In Addition To Food Insecurity

No Grave Dancing For Sam Zell Now. He’s Paying Up For Hot Properties

Investors Are Buying More of The U.S. Housing Market Than Ever Before (#GotBitcoin)

Cracks In The Housing Market Are Starting To Show

Biden Lays Out His Blueprint For Fair Housing

Housing Boom Brings A Shortage Of Land To Build New Homes

Wave of Hispanic Buyers Boosts U.S. Housing Market (#GotBitcoin?)

Phoenix Provides Us A Glimpse Into Future Of Housing (#GotBitcoin?)

OK, Computer: How Much Is My House Worth? (#GotBitcoin?)

Sell Your Home With A Realtor Or An Algorithm? (#GotBitcoin?)

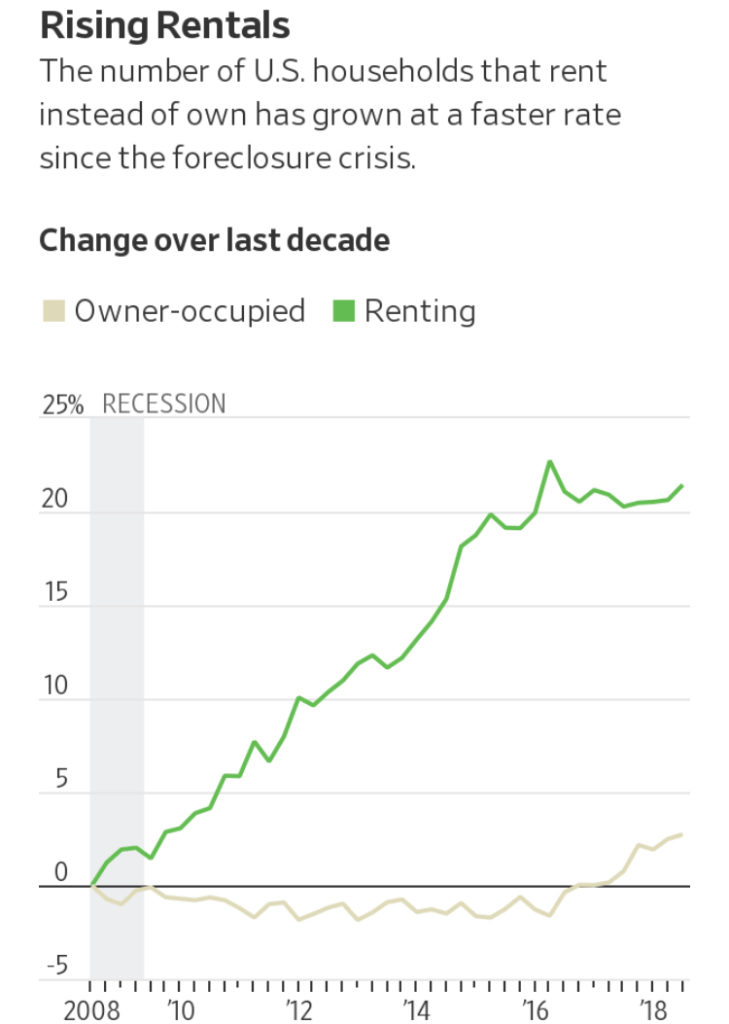

These companies are racing to meet demand for rental homes from a wave of young families too saddled with student debt to buy, as well as from investors wagering that the suburban renter class that swelled after last decade’s housing crash is here to stay.

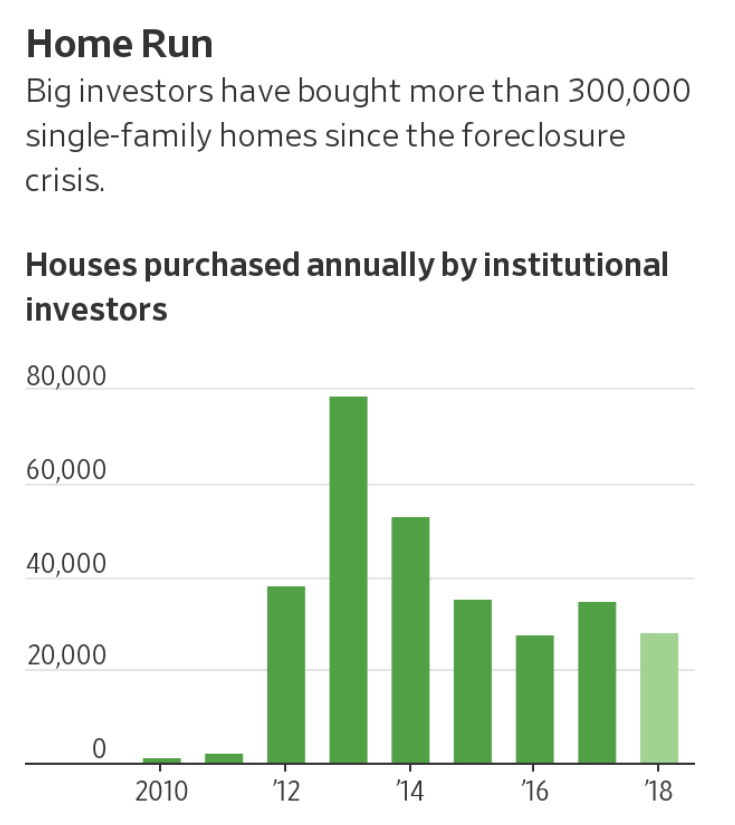

Acquiring newly constructed homes represents a sharp turn for institutional landlords such as American Homes 4 Rent and Tricon American Homes. Those companies and others like them emerged as bargain hunters at the depths of the housing crisis, when they gobbled up foreclosed homes by the thousands for far less than it would cost to build new ones.

The idea then was to accumulate enough homes in specific cities to make maintenance efficient and rent them to families who wanted to maintain suburban lifestyles and keep their children in good schools, but who couldn’t buy because of beaten-down credit and meager savings.

Surging property values since the recession have made bargains on houses harder to find. Yet those higher home prices have also improved the outlook for the rental business by making homeownership more difficult for millions of millennials.

Agoura Hills, Calif.-based American Homes 4 Rent has been building houses throughout the Southeast to add to its pool of more than 52,000 rental homes across the country. Chief Executive David Singelyn told a recent gathering of rental investors that in some places the company can build houses for about the same price that it costs to buy existing ones.

By building houses, American Homes avoids sales commissions and renovation costs. It can outfit homes with its preferred fixtures and finishes at the onset, and charge higher rents than it can fetch for its older homes, Mr. Singelyn said.

“You’re also going to have a brand new asset that has much lower maintenance costs over probably the first 10 years,” he said.

Tricon American Homes, a unit of Toronto-based Tricon Capital Group Inc., started adding new homes to its stable last year and has hundreds more in the works. The company, which has about 17,000 U.S. rental homes, made a deal in the summer with a Texas pension fund and a Singaporean sovereign-wealth fund to go on a three-year, $2 billion homebuying binge. The group says it intends to acquire as many as 12,000 single-family properties.

Tricon has purchased new houses and lots from builders and agreed to take big chunks of subdivisions up front to help developers get projects off the ground. Kevin Baldridge, Tricon’s president, said the company recently agreed to buy an entire 135-home phase of a subdivision outside of Houston he likened to a “horizontal apartment community,” and is weighing whether to start building homes itself.

The build-to-rent strategy is more about adding rental income than finding homes that will rise in value, said Terry Chen, Tricon’s acquisitions chief. “What we’re really after is the durable cash flow,” he said.

Not all big rental investors like the idea of building rental homes.

At the same industry gathering last month in Scottsdale, Ariz., where Messrs. Singelyn and Baldridge touted their build-to-rent strategies, Invitation Homes Inc. co-founder Dallas Tanner said he would listen to pitches from builders but didn’t want the Dallas-based company—the country’s largest single-family landlord with more than 82,000 houses—to take on development risk or push too far from city centers to try to make the numbers work on new construction. “It’s just not what we’re focused on,” Mr. Tanner said.

Some smaller investors said they have recently been getting their hands on brand-new homes at significant discounts without having to lift a hammer. They said they do it by approaching home builders during the waning days of fiscal periods, when executives are eager to jettison inventory to hit quarterly sales targets.

Bruce McNeilage, whose Nashville, Tenn.-based Kinloch Partners LLC flips packages of occupied rental homes in the Southeast to larger investors, has augmented his own construction projects with homes he acquires from builders on the cheap. By paying cash, he said, he is able to close deals in a day or so, as opposed to the months it might take someone who has to secure a mortgage. That approach has enabled him to squeeze discounts of up to 15% from builders in recent weeks, he added.

He said he pays full price so public records don’t show a decline in neighborhood sales prices and reaps the discount after closing through rebates from the builder. He also agrees not to use yards signs to advertise rentals, to avoid raising hackles among the neighbors.

Mike Kalis, who used to work for a big home builder but now runs Marketplace Homes, a Livonia, Mich.-based seller and manager of rental houses, said investors have to approach developers delicately. When home prices crashed a decade ago speculators walked away from deals in droves, leaving builders holding unsold homes—many of which were scooped up on the cheap during the recession by early rental investors.

“You kind of have to do it very quietly where they don’t know that you’ve picked off 30 homes that you’re going to convert into rental,” Mr. Kalis said.

Updated 5-29-2019

Blackstone Starts Selling Out of Home-Rental Empire

Private-equity firm late Tuesday sold more than $1 billion of shares of Invitation Homes.

Blackstone Group LP is cashing in on its bet on the suburban rental class.

The private-equity firm late Tuesday sold more than $1 billion of shares of Invitation Homes Inc., the giant single-family home landlord it launched following the financial crisis in a wager that many Americans would be willing to rent the suburban lifestyle they could no longer afford to own.

The share offering is Blackstone’s second since March and comes as Invitation’s shares are trading at a record, reflecting rising rents and strong demand for the 80,000-odd homes it owns in 17 markets around the country. Blackstone, which invested in Invitation from private-equity funds that are approaching deadlines to return cash to investors, now owns about 27% of Invitation’s shares, down from about 34% before the latest sale.

Invitation shares traded down slightly on Wednesday to $25.27, just below the $25.30 that Blackstone received in the offering. The stock is up more than 26% since debuting in a February 2017 initial public offering.

Those gains have come this year as Invitation and its main rival, American Homes 4 Rent , up 21% in 2019, have reported rising rents and occupancy rates along with reduced expenses. Concerns about whether the companies would be able to profitably manage tens of thousands of far-flung properties resulted in tepid responses to their shares until recently.

Investors have come around on the nascent rental-home sector as the companies have become more efficient operators and the national homeownership rate weakened amid an otherwise strong economy. Both companies target homes with at least three bedrooms in good school districts in hopes of attracting families who will stay in homes longer and pay more than apartment renters.

Invitation’s first-quarter results, which showed an uptick in tenants renewing leases, showed that its “renters may prove far stickier than once assumed,” Raymond James analyst Buck Horne said in a note to clients this month.

Blackstone joined several other financiers in gobbling up deeply discounted homes during the foreclosure crisis. The firm teamed with a group of real-estate investors in Phoenix and bought its first houses around the Arizona capital in April 2012. From there it spent roughly $10 billion, much of it borrowed, buying houses in hot job markets around the country. In 2017, Invitation merged with a rival rental-home operator formed by real-estate tycoons Barry Sternlicht and Tom Barrack.

So far Blackstone has reaped roughly $2 billion from its two share sales this year. It also has received a $682.5 million payout from Invitation before the company was public and about $197 million in dividends paid out on the firm’s shares since the IPO.

Updated: 11-21-2019

Blackstone Moves Out Of Rental-Home Wager With A Big Gain

Firm sells the last of its stake in invitation homes, the company it created after the housing crisis to scoop up foreclosed properties and rent them out.

Blackstone group inc. has closed the door on its giant rental-home gambit.

The investment firm late wednesday sold the last of its stake in invitation homes inc., invh -1.51% the company it created after the housing crisis to scoop up tens of thousands of foreclosed single-family properties from the courthouse steps, spruce them up and rent them out.

Blackstone began whittling its position in march through a series of bulky stock offerings. the last of which, on wednesday, was for nearly 11% of invitation’s shares and brought back about $1.7 billion. including dividends paid before and since invitation’s 2017 initial public offering, blackstone reaped about $7 billion in all, according to securities filings. that’s better than twice what the firm invested.

blackstone’s wager was that last decade’s historic collapse in home prices and advances in cloud computing and mobile technology would enable it to buy enough suburban houses to achieve economies of scale and then to efficiently manage tens of thousands of far-flung rental properties thereafter. to do so would be to tame the final frontier in real estate for institutional investors and gain a toehold in the largest asset class in the world: the u.s. single-family home.

“The hardest part wasn’t buying the homes, it was building the business,” blackstone president jonathan gray, who headed the firm’s real-estate business when it launched invitation, said in an interview. “we created a company from scratch. it was created on a yellow pad. it was an idea. now it’s a real business.”

As the number of foreclosed homes swelled and home prices hit bottom eight years ago, blackstone and other big real-estate investors pounced. blackstone, hotelier barry sternlicht and donald trump confidante tom barrack sent buyers to auctions with duffel bags of cashiers checks and instructions to buy anything that was cheaper than it cost to build new, not too old, big enough for a family and in a good school district.

Blackstone formed invitation with a group of phoenix investors who were buying trailer parks before the crash. they were led by dallas tanner, invitation’s 39-year-old chief executive, who at the time was fresh out of graduate school.

Starting with a three-bedroom stucco house on the outskirts of phoenix that it bought at auction for $100,700, invitation went on a $10-billion homebuying spree. its buyers streamed into foreclosure auctions across the sunbelt spending at a clip of more than $100 million a week. in about 18 months, it had bought 30,000 homes one by one and spent another $2 billion or so fixing them up.

When the flood of foreclosures subsided, the companies hit the open market looking for houses. they employ sophisticated house-hunting algorithms and increasingly build homes expressly to rent. invitation eventually absorbed the rental empires of messrs. sternlicht and barrack.

Invitation’s shares received a tepid response at the onset. lately, though, they have soared as the company has reported record occupancy and rents. its shares are up 50% this year despite blackstone liquidating its majority stake. rival american homes 4 rent, which owns about 53,000 homes to invitation’s 82,000, is up 34% this year.

The two companies compete at the high end of the rental market. their typical tenants aren’t quite 40, have a child or two and a household income of about $100,000. the landlords have capitalized on both the willingness of relatively high earners to rent the suburban lifestyle they can no longer afford, and disinterest in homeownership from younger americans who lack confidence in their employment and the housing market.

Though homeownership has bounced back from the 50-year lows reached in 2016, it remains well below last decade’s rates.

Mr. tanner said that blackstone’s “belief in the validity of our business model and their investments set us on a path to meet an underserved need in the housing market…we look ahead knowing we are well positioned to continue to help families live in great neighborhoods without the cost of homeownership.”

Updated: 5-11-2020

Wall Street Bets Virus Meltdown Gives Landlords A Chance To Grow

Largest home-leasing companies have strong occupancy, rent collection and expect demand for suburban houses to rise.

Wall Street’s wager on high-earning suburban renters is paying off, and it is raising its stakes.

Investors are flocking to America’s mega landlords, drawn by signs the companies that emerged from last decade’s foreclosure crisis owning huge pools of rental houses are weathering the economic shutdown far better than feared. Many also expect that the coronavirus pandemic will make suburban single-family homes both more desirable and more difficult to buy for even the relatively well-heeled.

Share prices of the largest home-rental companies, such as Invitation Homes Inc. and American Homes 4 Rent, have outpaced the broader stock market since they and the S&P 500 bottomed in late March. Invitation is up 57% since then and American Homes has gained 36%, compared with the S&P 500’s 31% climb.

Invitation, the country’s biggest single-family rental company, last week reported record occupancy of its roughly 80,000 houses and better-than-normal on-time rent payments in May—despite the pandemic leaving millions of Americans unemployed.

American Homes 4 Rent, the second largest with about 53,000 houses, said it isn’t much below its own pre-pandemic levels of rent collection or occupancy. The company said a $225 million venture to build rental houses that it struck with J.P. Morgan Asset Management in February was enlarged in recent weeks to $650 million.

Redwood Trust Inc. executives said that the bundler of real-estate debt was preparing to offer investors a fresh pool of loans to single-family landlords, even after the value of its mortgage-related assets collapsed.

Amherst Residential, which manages about 20,000 houses for big investors such as hedge funds and pensions, called off its planned acquisition of 15,000-home rival Front Yard Residential Corp. over the difficulties of integrating the two companies during the pandemic, including back-office functions in locked-down India. Amherst paid Front Yard a $25 million breakup fee, loaned it $20 million and bought $55 million of its shares at the above-market acquisition price.

Amherst still wants to add houses. President Drew Flahive said in an interview that the firm is negotiating separate house-hunting pacts with two large insurance companies.

“The amount of interest we’ve gotten in the last two or three weeks in terms of setting up private-market investments has really accelerated,” Mr. Flahive said. “We’re likely to see a really pronounced capital flow into single-family real estate.”

Investors weren’t so sure about rental houses at the onset of the pandemic. Bonds backed by rent payments traded down from face value. Shares of Invitation and American Homes plunged on worries about how many people would pay their rent. But the stocks have bounced back. Rent collections and tenant retention have proven far better than commercial property, such as office towers and shopping centers, and even apartments, which tend to have smaller household sizes and incomes than rental houses.

“Investors will be able to breathe a deep sigh of relief,” Raymond James analysts wrote in a note to clients. “Residential rent collection results…have been far more resilient than initially feared, proving to be a steady ship in a sea of turmoil.”

Invitation executives attributed the company’s record occupancy and strong rent collection to two main factors: the dual-income households earning about $110,000 that are its typical tenants and a shift to promoting occupancy of its houses with discounts instead of pushing up rents.

The company bought $28 million of houses in April but said it would pause purchasing once it completes another $19 million worth that it has under way. Meanwhile, it is hoarding cash, including $152 million of security deposits, in case tenants run into problems paying rent in the coming months.

“We will be able to pivot quickly to resume buying when the time is right,” said Ernie Freedman, Invitation’s finance chief.

Both Invitation and American Homes said there has been an uptick in leasing activity in recent weeks. That is partly thanks to their earlier investment in self-showing technology, such as electronic deadbolt locks, that was intended to eliminate the cost of staffing showings for so many scattered properties.

After a slow second half of March, April showings for American Homes rose 5% over the previous year and the company recorded some 9,500 showings during the last weekend of April and the first weekend of May. That is about six per available property, said operating chief Bryan Smith.

Rental executives say some recent move-ins chose to rent instead of buy given the economic uncertainty. Others have leased houses to get out of apartment buildings, given the contamination risks associated with close living.

“You have this squeeze from both sides,” said Amherst’s Mr. Flahive.

The executives say it is unclear whether historically low borrowing costs will prompt a surge of homebuying, or aspiring homeowners will be stymied by more restrictive mortgage lending. Either way, there may not be enough new suburban homes to meet demand, given the slowdown in construction.

“We’re still going to have the fundamental lack of supply to meet normal household formation,” said Invitation’s 39-year-old Chief Executive Dallas Tanner, who is the same age as the company’s typical tenant. “There are 65 million people between the ages of 20 to 35 coming our way.”

Updated: 11-10-2020

Race For Space Pushing Up Suburban Rents

America’s mega landlords have thrived since Covid-19 set off a scramble for suburban homes.

Big companies that own single-family homes are raising rents at the fastest rate since they emerged from last decade’s foreclosure crisis, capitalizing on a rush for suburban housing.

Though millions of Americans are still struggling to pay rent and at risk of eviction, the bet on six-figure-earning suburbanites by companies such as Invitation Homes Inc. and American Homes 4 Rent has so far been pandemic proof.

Occupancy of the hundreds of thousands of houses collectively owned by these companies is at record highs. Timely payments are in line with historical rates. Tenants are accepting rent increases instead of moving out. New renters hunting for home offices and outdoor space are paying up to move in.

A Covid-19 vaccine might make moving to the suburbs less urgent for some, but rental executives and investors expect favorable demographic and housing-market dynamics to outlast the pandemic.

“The demand we see today is totally insatiable, and it’s growing,” said David Singelyn, chief executive of American Homes 4 Rent, which owns more than 53,000 houses in 22 states and collects an average monthly rent of $1,686.

Asking rents for available properties owned by big home-rental firms jumped 7.5% in October, according to real-estate analytics firm Green Street. It was the fifth straight month of year-over-year increases and the biggest since the firm began tracking in 2014, when financiers were still gobbling up foreclosures.

Mom-and-pop operators and individual investors who own most of the country’s 16 million rental houses are also raising rents. But not as aggressively as America’s mega landlords, who use computer programs to match rents with demand and have their own investors to please.

September single-family rents climbed an average of 3.8% from a year earlier across 63 markets regardless of the owner, according to John Burns Real Estate Consulting. No market declined.

Increases in excess of 5% came in corporate-landlord strongholds Atlanta and Phoenix, but also in Middle America, around Memphis, Minneapolis and Kansas City, as well as in the West Coast’s less-expensive inland markets, like Sacramento, Calif. and Portland, Ore.

“Landlords are able to raise rents right now at a rate that is high in normal times,” said Rick Palacios Jr., John Burns’s head of research. “It’s ridiculously high when you put it in a backdrop of a recession”

The situation speaks to the uneven economic recovery. Multitudes of Americans remain unemployed and without the means to make up for missed rent payments once eviction moratoriums are lifted. Meanwhile, work-from-home professionals have kept earning and are looking for more living space.

American Homes 4 Rent and larger rival Invitation Homes are up 60% and 71%, respectively, since shares bottomed on March 23. The S&P 500 has climbed 59% since the market nadir. Shares of Toronto’s Tricon Residential Inc., which owns about 22,000 U.S. houses, have nearly doubled.

Progress by Pfizer Inc. and partner BioNTech SE toward a Covid-19 vaccine on Monday lifted shares of beleaguered apartment owners, whose tenants tend to be lower earners and most affected by the stalled service economy. Shares of single-family landlords and home builders declined on hopes that the pandemic will be brought under control with shots instead of lockdowns, weakening the suburbs’ pull.

Wall Street is betting on rental homes long term, though. Wealth managers, private-equity firms and other big investors have pumped billions of dollars into home-rental operations this year so that they can add houses.

These investors anticipate a wave of high-earning but debt-saddled millennials forming families and alighting to the suburbs in search of good schools and granite countertops.

Many are millennials drawing good salaries but carrying so much student debt that buying a home is difficult even with historically low mortgage rates.

The inventory of for-sale homes relative to the number of U.S. households is at its lowest level in decades, which has pushed prices to records in many markets. Builders have ramped up construction, but they aren’t adding much at the low-end. Just 10% of new homes sell for less than $200,000, down from nearly 45% a decade ago, according to John Burns.

American Homes 4 Rent executives say many new tenants are arriving from expensive coastal cities. The number of Californians applying to lease the company’s houses in Arizona, Nevada and Texas have been roughly twice what they were in 2019, operations chief Bryan Smith told investors last week on a call to discuss the company’s third-quarter earnings. Migration to Florida from New York and New Jersey has been similarly strong.

The Agoura Hills, Calif. company said that new lease rates for the summer quarter rose 5.9% and that October was up 7% from a year earlier. For a few months the company renewed expiring leases without increases, but by August it had resumed asking tenants to pay more at renewal. American Homes 4 Rent expects fourth-quarter renewals will rise 4%.

Invitation Homes, which owns more than 79,000 houses and collects an average monthly rent of $1,881, raised new lease rates 5.5% during the third quarter. Renewals rose 3.3%. Executives say they have been more aggressive since September, when the quarter ended, but are mindful of risking move outs.

“We’re not going to push too hard into the winter here when we don’t have a vaccine and we know that there may be some moments where there’s going to be some uncertainty,” said Charles Young, the Dallas company’s operation chief. “We’re just trying to find that right balance.”

Updated: 1-8-2021

Rental Home Construction Climbs As Purchase Prices Surge

Investors are betting Americans will keep flocking to spacious suburban living even if they can’t afford to buy.

There haven’t been so many single-family homes under construction in the U.S. since 2007, yet many of these new houses won’t be for sale.

Investors are building tens of thousands of houses expressly to rent in a bet that Americans will keep flocking to spacious suburban living even if they can’t afford to buy homes.

The Covid-19 pandemic sparked a race for space among Americans, and home prices have surged to records. The gains have outpaced wage growth, straining affordability despite historically low borrowing costs.

Homeownership is unaffordable for average wage earners in 55% of U.S. counties, up from 43% a year earlier, according to Attom Data Solutions, a real-estate analytics firm. Meanwhile, single-family landlords have reported record occupancy and fast-rising rents since the pandemic began.

Individuals, family offices, pension funds and Wall Street’s boldfaced names are shoveling billions of dollars into build-to-rent projects.

Home builders are embracing the business of selling houses wholesale to landlords, and even teaming up with them to build neighborhoods that blur the line between houses and apartment complexes.

“Every institutional investor is considering this space,” said Trevor Koskovich, who heads investment sales at the property-deal adviser NorthMarq and recently represented the seller of five gated rental communities around Phoenix. They fetched $235.5 million from a Chicago investment firm.

The 943 one- and two-bedroom houses have their own street addresses, include slivers of outside space and share swimming pools. Their developer, Christopher Todd Communities, has teamed up with the builder Taylor Morrison Home Corp. to replicate these rental villages across the Sunbelt.

“Our confidence in this opportunity has only increased over the last year,” said Sheryl Palmer, Taylor Morrison’s chief executive. Darin Rowe, who runs the home builder’s rental business, expects the portion of new U.S. homes that are sold straight to investors to exceed 5% over the next few years, up from the historical average of 1% or so.

From clustered cottages to cul-de-sac McMansions, more than 50,000 houses were built specifically to serve as rentals during the 12 months ended Sept. 30, according to John Burns Real Estate Consulting.

That tally—well above the 31,000 average over the past four decades—is likely low since it misses one-offs in which end use isn’t specified by building permits as well as houses in typical subdivisions that are sold to investors, said Rick Palacios Jr., the consulting firm’s head of research.

Executives at LGI Homes Inc., for instance, have said that bulk sales to landlords would account for as much as 10% of the builder’s 2020 home sales, or as many as 900 houses.

The build-to-rent boom was sparked a couple of years ago, when the megalandlords that emerged from the housing crisis were looking for ways to grow after they soaked up the flood of cheap foreclosures.

Big companies including American Homes 4 Rent and Tricon Residential Inc. took to buying houses on the open market. But there is competition from regular house hunters for a limited number of desirable properties at the lower end of the market.

“The banks and lenders stopped providing financing to the lower middle class and so home builders stopped building entry-level homes,” said Thibault Adrien, whose Lafayette Real Estate began buying foreclosed homes a decade ago. “The last way to increase our exposure was to build our own.”

It was counterintuitive for businesses built on deeply discounted properties to start paying more than replacement cost to add houses, said Mr. Adrien. But after testing the strategy outside Tampa, Fla., Lafayette went all in.

Building made it possible for investors to outfit houses with their preferred fixtures and finishes at the onset. Plus, landlords found that renters were willing to pay premiums to move into brand-new houses.

“Imagine if consumers could only lease old cars, not new cars,” said Mr. Palacios. “That’s how single-family rentals have been.”

Lafayette teamed up with the private-equity firm Carlyle Group Inc. and has about 1,200 houses recently completed or under way.

American Homes 4 Rent, which owns about 53,000 houses, formed a $625 million venture with J.P. Morgan Asset Management to add to what was already the most prolific output of new rentals. American Homes 4 Rent has built 2,500 houses in more than 60 neighborhoods and has dozens more subdivisions in development.

Its Celery Cove subdivision outside Orlando, Fla. is representative, with 37 three- and four-bedroom houses that lease monthly from the $1,700s.

Tricon has a similar, $450 million partnership to build rentals with the Arizona State Retirement System.

The Toronto firm said it is considering raising another fund, which could have $1 billion of spending power, to buy homes from builders.

Those homes are generally indistinguishable from owner-occupied properties and can be bought and sold one by one. Many investors are opting for projects that are closer to apartment complexes.

Investors and lenders said hybrid projects, such as Christopher Todd’s, can be financed more favorably than the same number of scattered homes while having advantages over apartments, such as being able to lease units as they are ready rather than waiting for an entire building’s completion. Developers can also adjust plans if demand falls short.

“That really mitigates some of the risk,” said Ivan Kaufman, chief executive of Arbor Realty Trust Inc., which has originated about $1 billion of loans to build-to-rent projects over the past two years.

Updated: 5-9-2021

Rent Surges On Single-Family Homes With Landlords Testing Market

Record occupancy rates are emboldening single-family landlords to hike rents aggressively, testing the limits of booming demand for suburban rentals.

American Homes 4 Rent, which owns 54,000 houses, increased rents 11% on vacant properties in April, according to a statement Thursday. Invitation Homes Inc., the largest landlord in the industry, boosted rents by similar amount, an executive said on a recent conference call.

Housing costs are jumping across the U.S. as vaccines fuel optimism about a rebound from the pandemic.

With homeownership out of reach for many Americans, rents are also climbing. The increases may add to concerns about inflation pressures as the economy recovers.

“Companies are trying to figure out how hard they can push before they start losing people,” said Jeffrey Langbaum, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. “And they seem to be of the opinion they can push as far as they want.”

In the early months of the pandemic, the big single-family rental companies slowed rent hikes, preferring to maximize occupancy during an uncertain time for the economy. Now, low vacancies are giving them pricing power.

Invitation Homes reported an occupancy rate of more than 98% during the first quarter, freeing the company to raise prices by more than 10% on vacant houses in April. Invitation Homes is targeting increases of as much as 8% for tenants seeking to renew leases in coming months, an executive said on a recent conference call.

Single-family landlords have had the upper hand over apartment owners in the age of remote work, but those advantages might dissipate as employers summon workers back to the office.

“How much of the demand is temporary?” said Langbaum. “I do believe some component of it will revert back to urban markets.”

Updated: 6-18-2021

America Should Become A Nation of Renters

The very features that made houses an affordable and stable investment are coming to an end.

Rising real-estate prices are stoking fears that homeownership, long considered a core component of the American dream, is slipping out of reach for low- and moderate-income Americans. That may be so — but a nation of renters is not something to fear. In fact, it’s the opposite.

The numbers paint a stark picture. After peaking at 69% in 2004, the homeownership rate fell every year until 2016, when it was 64.3% — its lowest level since the Census Bureau started keeping track in 1984.

The rate rebounded in Donald Trump’s presidency, hitting 66% in 2020, but that trend is likely to be arrested by a housing market that is desperately short on supply and seeing month-over-month price increases greater than they were in the frenzied market of 2006.

This process is painful, but it’s not all bad. Slowly but surely, most Americans’ single biggest asset — their home — is becoming more liquid. Call it the liquefaction of the U.S. housing market.

Even in the best markets, single-family homes have historically been an extremely illiquid asset.

Appraisals have to be made on an individual basis, and mispriced homes can sit on the market for months waiting for a potential buyer — only for that buyer’s financing to fall through.

Liquid assets, like publicly traded stocks and corporate bonds, earn what’s known as a liquidity premium: Their market price is many times the dividend or coupon that investors get from holding them. The more liquid an asset, the higher that premium goes. On the flip side, those same high-flying stocks and bonds can see their prices collapse when investors get spooked and withdraw their cash from the market.

Houses have typically traded with very little liquidity premium. That meant a relatively low purchase price compared to what it would cost to rent — the equivalent of the dividend from housing investment — and stable prices over time.

These two factors made houses a good investment for moderate-income families who often lacked the cash and the risk tolerance for market investments. As investments went, single-family homes were cheap and slowly grew in value in both good times and bad.

In the early 21st century, automated appraisals and mortgage underwriting began to change that.

Combined with the repackaging of subprime loans into presumably safer CDOs, they created a far more liquid market for housing. In response, housing prices soared — and became more sensitive to the vagaries of the markets. When investors pulled out of CDOs, buyer financing dried up and the whole housing market crashed.

It may have seemed at the time like a failed experiment. But financialization had changed the housing market forever. Houses are now more prone to be priced high relative to rents, and to see their prices fluctuate with the market. The very features that made home buying an affordable and stable investment are coming to an end.

But the illiquidity that made houses a safe investment also made America less dynamic and mobile.

In coastal markets with strong demand for housing, market forces would normally have led to the replacement of single-family homes with duplexes and apartments. But existing homeowners are reluctant to agree to development with unknowable effects on the value of their most precious investments.

The result is less development — and sky-high rents for any residents not lucky enough to own their own home.

As institutional investors increasingly enter the housing market, however, the incentives begin to shift. Large investors can expand or redevelop their properties themselves, because they benefit from a greater number of overall tenants, even if rents themselves dip.

Meanwhile, the increased availability of rental properties could benefit homeowners in declining areas of the country. They frequently cannot move to more prosperous areas because they can’t sell their homes for nearly enough to buy a new place somewhere else. In an economy with more rentals, however, they could afford to try a new place for a few years without the commitment of a mortgage or down payment.

A nation of renters could lead to a world where location decisions are driven far more by personal preferences and life-cycle demands. Younger workers might prefer the excitement of the city. A couple just starting a family could reunite with their parents or siblings in a small town.

The U.S. is not quite there yet, and not just because too many people are chasing too few apartments. To see the U.S. as a nation of renters requires a revision of the American dream of homeownership. This country was always more about new frontiers than comfortable settlements, anyway.

Updated: 6-22-2021

Blackstone Moves Out Of Rental-Home Wager With A Big Gain

Firm sells the last of its stake in Invitation Homes, the company it created after the housing crisis to scoop up foreclosed properties and rent them out.

Blackstone Group Inc. has closed the door on its giant rental-home gambit.

The investment firm late Wednesday sold the last of its stake in Invitation Homes Inc., the company it created after the housing crisis to scoop up tens of thousands of foreclosed single-family properties from the courthouse steps, spruce them up and rent them out.

Blackstone began whittling its position in March through a series of bulky stock offerings. The last, on Wednesday, was for nearly 11% of Invitation’s shares and brought back about $1.7 billion. Including dividends paid before and since Invitation’s 2017 initial public offering, Blackstone reaped about $7 billion in all, according to securities filings. That’s better than twice what the firm invested.

Blackstone’s wager was that last decade’s historic collapse in home prices and advances in cloud computing and mobile technology would enable it to buy enough suburban houses to achieve economies of scale and then to efficiently manage tens of thousands of far-flung rental properties thereafter. To do so would be to tame the final frontier in real estate for institutional investors and gain a toehold in the largest asset class in the world: the U.S. single-family home.

“The hardest part wasn’t buying the homes, it was building the business,” Blackstone President Jonathan Gray, who headed the firm’s real-estate business when it launched Invitation, said in an interview. “We created a company from scratch. It was created on a yellow pad. It was an idea. Now it’s a real business.”

As the number of foreclosed homes swelled and home prices hit bottom eight years ago, Blackstone and other big real-estate investors pounced. Blackstone, hotelier Barry Sternlicht and Donald Trump confidante Tom Barrack sent buyers to auctions with duffel bags of cashier’s checks and instructions to buy anything that was cheaper than it cost to build new, not too old, big enough for a family and in a good school district.

Blackstone formed Invitation with a group of Phoenix investors who were buying trailer parks before the crash. They were led by Dallas Tanner, Invitation’s 39-year-old chief executive, who at the time was fresh out of graduate school. Starting with a three-bedroom stucco house on the outskirts of Phoenix that it bought at auction for $100,700, Invitation went on a $10-billion homebuying spree.

Its buyers streamed into foreclosure auctions across the Sunbelt spending at a clip of more than $100 million a week. In about 18 months, it had bought 30,000 homes one by one and spent another $2 billion or so fixing them up.

When the flood of foreclosures subsided, the investors hit the open market looking for houses. They employ sophisticated house-hunting algorithms and increasingly build homes expressly to rent. Invitation eventually absorbed the rental empires of Messrs. Sternlicht and Barrack.

Invitation’s shares received a tepid response at the onset. Lately, though, they have soared as the company has reported record occupancy and rents. Its shares are up 46% this year despite Blackstone liquidating its majority stake. Rival American Homes 4 Rent, which owns about 53,000 homes to Invitation’s 82,000, is up 31% this year.

The two companies compete at the high end of the rental market. Their typical tenants aren’t quite 40 and have a child or two and a household income of about $100,000.

The landlords have capitalized on both the willingness of relatively high earners to rent the suburban lifestyle they can no longer afford, and disinterest in homeownership from younger Americans who lack confidence in their employment and the housing market.

Though homeownership has bounced back from the 50-year lows reached in 2016, it remains well below last decade’s rates.

Mr. Tanner said that Blackstone’s “belief in the validity of our business model and their investments set us on a path to meet an underserved need in the housing market…we look ahead knowing we are well positioned to continue to help families live in great neighborhoods without the cost of homeownership.”

Updated: 6-22-2021

Blackstone Bets $6 Billion On Buying And Renting Homes

Deal for Home Partners of America, owner of over 17,000 houses in U.S., is latest sign Wall Street believes housing market will stay hot.

Blackstone Group Inc. has agreed to buy a company that buys and rents single-family homes in a $6 billion deal, a sign Wall Street believes the U.S. housing market is going to stay hot.

The investment firm confirmed Tuesday that it has reached a deal to acquire Home Partners of America Inc., which owns more than 17,000 houses throughout the U.S. Home Partners buys homes, rents them out and offers its tenants the chance to eventually buy. The deal had been reported earlier by The Wall Street Journal.

U.S. home sales soared last year at their fastest pace in 14 years, when low mortgage rates and the rise of remote work during the pandemic sent buyers scrambling to find larger living spaces.

The lack of homes for sale relative to demand and record housing prices have slowed the pace of home sales in recent months. But on a historic basis, the market remains red hot, and analysts say demand from millennials entering their prime homebuying years is expected to fuel demand for years to come.

The median price for existing homes topped $350,000 for the first time in May, the National Association of Realtors said Tuesday. “That supply-demand imbalance will not be fixed overnight,” said Kathleen McCarthy, global co-head of Blackstone Real Estate.

Blackstone was among the big investment firms to buy houses in bulk in the aftermath of the subprime crisis, when lenders sold off foreclosed homes at marked-down prices. The New York firm built a portfolio of tens of thousands of single-family homes, then rented them out through a company called Invitation Homes Inc.

In 2019, Blackstone exited from the single-family rental business when it sold its last shares in Invitation Homes, which had become the largest U.S. firm in this industry with 80,000 homes for lease. The firm put its toe back in the market in 2020 by investing $240 million to buy a preferred equity stake in Toronto’s Tricon Residential Inc., which buys single-family rentals in North America.

Blackstone’s deal for Chicago-based Home Partners shows that the investment firm is turning even more bullish on U.S. housing.

The firm is rejoining an expanding roster of Wall Street powerhouses that have acquired single-family rental companies.

Canadian property giant Brookfield Asset Management Inc. recently acquired a stake in a landlord that owns more than 10,000 U.S. homes. J.P. Morgan Asset Management and Rockpoint Group LLC also have made big investments in single-family rental operators.

The business is attractive to investors because growth can come from both rising home prices and rent increases. The S&P CoreLogic Case-Shiller National Home Price Index, which measures average home prices in major metropolitan areas across the nation, rose 13.2% in the year that ended in March, up from a 12% annual rate the prior month.

The rental market showed signs of softness during the pandemic, especially in downtowns that saw an exodus of residents. But lately rents, too, have begun to rise.

Median asking rents rose 1.1% annually in March to $1,463 a month across the country’s 50 largest markets, according to a report from Realtor.com.

Many analysts say that with home-price gains showing little sign of easing, rents can continue growing throughout the U.S. as would-be home buyers are priced out of the sales market and are compelled to keep renting.

For all their recent activity, big institutional investors own about 300,000 U.S. homes, or only 2% of single-family rental homes, according to a report by New York-based financial firm Amherst Pierpont Securities LLC. About 85% of the single-family rental market is owned by investors with 10 or fewer properties, the firm said.

Home Partners, founded in 2012, has a different business model from Invitation Homes and some of the other big firms in the single-family rental business. It gives renters the option to buy at a predetermined price at any time with 30 days’ notice.

To that end, Home Partners limits its acquisition of new houses to those homes identified by people as ones they would possibly like to buy after renting.

Ms. McCarthy said about 20% of Home Partners’ renters have ended up exercising their options to buy their homes. She said she expects that rate to increase because, given recent home-price appreciation, many Home Partners renters buying today would likely be paying a price below current market value.

Blackstone is buying Home Partners through an investment fund named Blackstone Real Estate Income Trust, which primarily raises money from small investors and tends to hold assets longer than the firm’s opportunistic funds. That strategy is a sign that Blackstone thinks the housing market rally could last many years.

Home Partners chose Blackstone’s all-cash offer after a competitive bidding process, according to Blackstone. The deal is expected to close later this year.

Updated: 6-26-2021

Investors Chasing Housing Target Massive Pools of Airbnb Rentals

Investors hunting for returns in the frenzied U.S. real estate market are tapping a new strategy: building massive portfolios of houses to rent out on Airbnb.

A recent filing reveals that Dublin, Ohio-based ReAlpha is seeking to spend as much as $1.5 billion, including debt, to buy short-term rentals at an unprecedented scale. The money would be enough to purchase roughly 5,000 homes, Chief Executive Officer Giri Devanur said in an interview.

Emboldened by a post-pandemic travel boom and searching for better returns than they can get in hotels or apartment buildings, other firms are building on the strategies employed by the scrappy entrepreneurs who built small portfolios of short-term rentals and helped drive Airbnb Inc.’s decade-long rise.

Plans to buy giant pools of rentals would mark a shift toward a consumer experience with Airbnb that more closely resembles a hotel stay. But it comes as record-low home inventory pushes prices higher for average buyers and Wall Street investors alike.

“The business model has been proven, and now the opportunity is to do this at scale,” said Scott Shatford, CEO of AirDNA, which provides data and analytics to the industry. “People can’t figure out how to deploy capital quickly enough.”

Fast Decisions

Devanur, who took enterprise-software company Ameri100 public in 2017, said he wants to open up access to real estate investing by letting regular people buy fractional ownership of short-term rentals on his company’s app.

ReAlpha plans to use artificial intelligence software to evaluate home listings and make fast decisions on how much it’s willing to pay. The company will target markets including Austin, Dallas and Miami, where it can acquire 100 to 500 homes. And it’s exploring ways to buy discounted homes when a federal foreclosure moratorium ends.

“We have spoken to a bunch of banks where we can buy hundreds of properties at a time,” Devanur said. “We can analyze thousands of properties in a minute. For us, everything is through technology.”

Rental Rise

Airbnb’s rise over the last decade inspired a generation of entrepreneurs who buy, furnish and manage vacation rentals on a small scale. Larger companies also sprung up, often focusing on managing properties as opposed to owning them. In some cases, they branded their offerings, creating lodging businesses akin to Courtyard by Marriott or Hampton Inn.

Venture capitalists, meanwhile, backed companies that leased apartments from building owners and converted them into a new category of hotel. One such firm, Sonder, is slated to go public through a merger with a blank-check company later this year.

Lodging Firm Sonder Agrees to $2.2 Billion Gores SPAC Merger

Still, owning short-term rental homes in far-flung locations is challenging. It requires owners to route house cleaners and maintenance people across large areas. While long-term leases protect owners of offices, apartments and warehouses from economic shocks, the hospitality industry enjoys no such buffer.

Blackstone Bets $6 Billion on Shifting Path to Suburban Homes

Acquiring homes won’t be easy at a time when low inventory is pushing prices higher, and investors like Blackstone Group Inc., KKR & Co., and others commit billions of dollars to buying single-family rental homes.

Higher Prices

Short-term rental investors can focus on different types of homes than regular buyers or Wall Street landlords, but the capital pouring into residential real estate from all corners will make houses more expensive to come by.

For Airbnb, the arrival of larger, more sophisticated investors could be a blessing, even if it contradicts the company’s efforts to market itself as a way for travelers to experience new places like local residents. Large investors represent a potential source of new listings, and may offer a product that appeals to people who like the comfortable uniformity of hotels.

A representative for Airbnb declined to comment.

Growing appetite for short-term rentals will attract tens of billions of dollars in the years to come, said Sean Breuner, whose company, AvantStay, manages branded properties that offer concierge services. It also operates a brokerage to help investors find real estate.

“It is the last remaining asset class with any yield remaining,” said Breuner. “We believe there is a huge opportunity to institutionalize.”

Updated: 6-26-2021

KKR Makes New Single-Family Rentals Bet As Wall Street Piles In

KKR & Co. is making a fresh play for the suburbs, forming a new single-family landlord, My Community Homes, that plans to buy and manage rental houses across the U.S.

KKR is investing in the platform through its real estate and private credit funds, according to people with knowledge of the matter, who asked not to be identified because the matter is private. The number of homes and geographies targeted by the venture couldn’t immediately be learned.

A representative for New York-based KKR declined to comment.

The firm’s latest wager comes as Wall Street plows money into rental homes, betting that aging millennials will want larger living spaces to raise kids, and low inventories lift prices out of the reach of many families.

KKR’s credit arm previously backed Home Partners of America, a single-family rental company that Blackstone Group Inc. agreed this week acquire for $6 billion. The firm is set to generate a roughly 20% internal rate of return, or IRR, from its 2014 and 2018 investments in the company, a person with knowledge of the matter said.

Elsewhere in the sector, Centerbridge and Allianz Real Estate said in March they led a $1.25 billion equity commitment to Upward America Venture, a partnership with Lennar Corp. that intends to buy homes. And Invesco Real Estate recently backed Mynd Management to spend as much as $5 billion on buying single-family rentals.

Miami-based My Community Homes is led by Chief Executive Officer Marcos Egipciaco, whose prior company, Sovereign Real Estate Group, helped institutional investors buy single-family rentals. His latest effort has hired staff in Florida, Georgia and Indiana, and has open positions in North Carolina, according to LinkedIn.

Updated: 7-25-2021

Property Investors Bed Down In The Family Home

Big investing firms aren’t crowding out normal house buyers yet, but they are likely to become more controversial players in the residential market.

Wall Street firms are more eager than ever to buy family homes. If they snap up existing supply rather than help build new dwellings, they risk killing their latest golden goose.

Last week, Blackstone’s real-estate investment trust bought a portfolio of apartments for $5.1 billion from insurer American International Group. In June, the investment firm spent $6 billion on Home Partners of America, a company that owns more than 17,000 houses across the U.S. and offers renters an option to buy. Private-equity giant KKR launched a new division that will buy homes to rent them out, Bloomberg reported.

Meanwhile in Europe, property investors are increasing the share of their portfolios invested in residential real estate, and German landlord Vonovia recently launched an €18 billion takeover of competitor Deutsche Wohnen, equivalent to $21.2 billion.

Although rented homes are becoming a hot trade among big investors, the trend isn’t new. Blackstone made lucrative bets on foreclosed houses in the aftermath of the 2008-09 downturn. And there isn’t evidence yet that institutional investors are crowding out average home buyers. They bought just one in 500 U.S. homes sold in the 12 months after the Covid-19 crisis began, according to Amherst Capital.

However, big investors’ activity will increase now that the pandemic has made owning family homes more attractive. While the rents collected from commercial real-estate assets such as malls and offices took a hit during the Covid-19 crisis, most private residential tenants continued to pay up. Family homes could be an even better long-term bet than owning e-commerce warehouses. Real-estate research firm Green Street estimates that renting out U.S. single-family homes will deliver annual returns of 6.6%—versus a forecast of 6.3% for industrial property.

Buying up homes solves several headaches for powerful investors. Housing is a large asset class so can mop up a lot of excess cash. The submarket for rented single-family homes alone is worth approximately $3.1 trillion, according to Amherst—40% larger than the value of all U.S. offices and more than triple the value of all the country’s hotels. Renting out homes is also a good hedge against inflation. Over the past four years, rents have increased by 15% on average across Europe, Colliers data shows.

It’s unclear how many family homes the financial giants can snap up before there is a public backlash. Institutional investors already own 55% of the U.S. supply of multifamily homes, typically condos. However, they are minnows in the most appealing part of the housing market: Currently, just 2% of all the single-family properties available for rent in the U.S. are in the hands of institutional investors, according to Amherst.

Throughout the pandemic, publicly traded real-estate investment trusts that specialize in these kinds of family dwellings such as Invitation Homes and American Homes 4 Rent have outperformed those like AvalonBay that own apartment blocks.

But housing is politically sensitive, especially as skyrocketing prices over the past 18 months have put homeownership out of reach for more voters. As a multiple of household income, the median U.S. home is now pricier than in the run up to the 2008 housing crash, UBS analysis shows. Any sign that big investors are making it harder for ordinary buyers to get on the property ladder will be controversial.

Some governments are already tightening the screws. Since real-estate investor Round Hill Capital bought newly built homes in Ireland that would normally be marketed to first-time buyers, the country’s politicians have raised property taxes to stop institutional investors from snapping up family dwellings. Rent regulations are being considered in large Spanish cities like Madrid and Barcelona to cap spiraling housing costs.

The best way for big investment firms to get exposure to residential property without provoking a crackdown is to help build new supply. Some got the message: British bank Lloyds recently said it would invest in rented property to diversify its income, but added that it plans to build most of its portfolio from scratch. Blackstone’s purchase of AIG’s portfolio of apartments for low-income tenants looks more contentious.

The rub is that easing the housing shortage isn’t actually in investors’ financial interest. A lack of supply, coupled with the fact that more young families are priced out of homeownership, is precisely what will drive the fat returns expected in rented real estate over the next few years. Adding new supply could make these bets less lucrative and would also mean taking on development risk just as construction costs are rising sharply.

But to venture into such touchy real estate, investors must weigh this trade-off to avoid being ejected from the family home.

Updated: 9-14-2021

Soaring Rents Make It A Very Good Time To Own An Apartment Building

The 10% rise in national asking rents in August is highest on record, helped by more young workers returning to cities.

Despite a yearlong national eviction ban and continuing pandemic, it has rarely been a better time to be a big apartment-building landlord.

National asking rents rose 10.3% in August, measured on an annual basis, according to Real Page, a rental-management software company, which analyzed more than 13 million professionally managed apartments. That marked the first double-digit increase in the more than 20 years this data has been collected, and in several hot cities the rent increases were much greater than the national figure.

“The rent growth that we’re seeing in places like Phoenix and Las Vegas and Tampa, it’s obviously unprecedented,” said Jay Parsons, deputy chief economist for Real Page. August rents rose more than 20% year over year in each of these cities. Monthly rents were up more than 20% in smaller markets like Boise, Idaho, and Naples, Fla., too.

Fast-rising rents reflect several factors, analysts say. Younger adults who lived with family last year are now renting their own apartments, in many cases as they prepare to head back to the office. Middle-income workers who have been priced out of the scorching housing market have little choice but to pay higher rents. Limited growth in new apartment supply, meanwhile, can’t keep up with demand.

Apartment occupancy rates, a key metric for helping landlords determine how much they can increase rent, hit a record high of 97.1% in August. Household incomes for new renters at professionally managed properties also reached a new high of more than $70,000 a year, according to Real Page. An end to the federal eviction ban last month is likely to further strengthen landlords’ hands.

Multifamily-property values have increased 13% since before the pandemic, according to real-estate securities advisory Green Street. More money is being invested now in apartment buildings than in any other type of commercial real estate, according to data company Real Capital Analytics.

Few analysts predicted this scenario 18 months ago. When Covid-19 hit, the U.S. unemployment rate rose to nearly 15%. Surveys showed an increasing number of renters falling behind on their payments, and federal and local eviction bans often meant these tenants couldn’t be replaced.

Uncertainty about rent collections sent chills through the debt markets, raising concerns about a liquidity crunch in multifamily real estate.

Now, most segments of the multifamily market look strong. Even as more renters migrate back to cities, suburban markets continue to sizzle as record-high home-sale prices keep more people in rental housing. Others are relocating and working from home.

“Multifamily is able to capitalize on both of those trends,” said Karlin Conklin, principal of Investors Management Group, which has buildings in the suburban areas of cities like Raleigh, N.C., and San Antonio.

The rent increases mean that tenants who enjoyed big discounts last year are in for a rude awakening. In Nashville, Tenn., 27-year-old business analyst Zachary Wendland rented a one-bedroom apartment in a luxury rental high-rise for $1,420 a month in October. In June, the building was sold to Camden Property Trust, a publicly traded landlord, in one of the priciest-ever multifamily sales in the city.

Mr. Wendland wasn’t given the option to renew his lease with the new owner, but a similar unit in the building is now on the market for $2,199. “I couldn’t imagine a year ago paying $2,000 to live here,” he said. Now, he is apartment hunting again.

At the Nashville building, only six out of 430 units are available to rent, said Ric Campo, chief executive of the building’s new owner, Camden Property Trust. The mounting demand from high-paid professionals and transplants means rent increases between leases are getting bigger. “It’s not just Nashville. It’s pretty much every market,” Mr. Campo said.

Some individual investors have felt excluded from the rent rally. These landlords own about 41% of all rental properties nationwide, including the majority of single-family rentals, according to U.S. Census Bureau surveys.

Unemployment for lower-income workers caused many renters to miss payments, and eviction bans usually meant landlords had limited recourse. These building owners don’t have the scale to absorb unpaid-rent problems as easily as a corporate owner with thousands of apartment units.

A recent survey of about 1,000 small rental owners from the National Rental Home Council, a landlord trade group for single-family rental-home owners, found that one-third had sold or planned to sell a rental home because of the effects of the eviction moratorium on their business, with most selling to owner-occupiers.

Still, if unpaid rent is pushing more rental-home landlords to exit the business, it couldn’t come at a better time. National home-sale prices are up 18% over the past year.

Mortgage lending to multifamily owners has returned to pre-pandemic levels. Many landlords have tapped ultralow interest rates to refinance their mortgages, increasing their cash on hand and lowering their mortgage payments, said Jamie Woodwell, vice president of research and economics at Mortgage Bankers Association, a real-estate-lending industry group.

Much of the pandemic lending was driven by the government-backed mortgage programs, he said. But other lenders have since ramped up their multifamily business.

“You don’t have a single private source of capital that isn’t interested in lending on multifamily,” said Willy Walker, chairman and chief executive of commercial real-estate firm Walker & Dunlop Inc.

Where landlords have problems with their loans, the federal government has stepped in to help. The Department of Housing and Urban Development, and the government-backed mortgage giants Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, crafted forbearance programs for covered building owners who saw drops in their rent collections.

The Federal Reserve Bank also stepped in to purchase more than $10.5 billion in multifamily mortgage-backed securities since last spring, which helped encourage more lending.

The $46 billion in emergency rental assistance provided by Congress—and in most cases paid directly to landlords—is also slowly starting to help more building owners with unpaid rent. “That assistance has been extraordinary,” said Ms. Conklin. Her company has earned back 25% of its unpaid rent and expects more in the coming months, she said.

For most real-estate companies, going under because of unpaid rent is “unlikely,” Mr. Walker said. “There are not many operators who have such a high level of nonpayment that it is going to cause them to default on their loan,” he said.

Updated: 9-15-2021

New York Renters Face 70% Increases As Pandemic Discounts Expire

The era of widespread Covid concessions for apartment hunters is over.

The pandemic-era rental market in Manhattan gave people the chance of a lifetime to move into the apartment of their dreams. Ten months is all they got.

Landlords are jacking up rents — often by 50, 60 or 70% — on tenants who locked in deals last year when prices were in freefall. Some renters are being forced to move at a time when the market is roaring back to nearly pre-pandemic levels. And concessions are slipping away.

Andy Kalmowitz didn’t think twice in November before signing a 10-month lease on a two-bedroom, two-bathroom apartment in the desirable East Village neighborhood for $2,100 a month. When it was time to renew, his landlord asked for $3,500, a 67% increase.

“When I asked why, they said, ‘It’s a different world,’” said Kalmowitz, 24, who works in TV and had moved from New Jersey.

Across New York, landlords last year were forced to cut rents and offer freebies when the Covid-19 pandemic all but shut down the city, scattering residents who were looking for additional space or more-affordable housing.

Now the market has rebounded, and people appear to be flooding back: Large employers are demanding people return to the office, universities are ramping up in-person teaching and New York City’s public-school system — the largest in the country — has reopened without a remote-learning option.

“More are moving back from out of town, after being away quarantining for the past 18 months,” said Bill Kowalczuk, a broker at Warburg Realty. “There are more inquiries, more apartments renting within a week or less of the list date, and more prices going over the asking price than I have ever seen.”

The median asking rent in Manhattan rose to $3,000 in July, the highest it’s been since July 2020 and up from the pandemic low of $2,750 in January 2021, according to StreetEasy.

Across the borough, rents are still below pre-Covid levels. But in some particularly popular neighborhoods — including the Flatiron district, the East Village, the Financial District and Nolita — they’ve surged higher than before the pandemic, according to StreetEasy. Landlords are still offering incentives, but they’re not as common and typically only apply to new leases, not renewals, realtors say.

Kalmowitz tried to negotiate. He offered $3,000, but his landlord wouldn’t budge. Eventually, he and his roommate moved 10 blocks south to an apartment on the Lower East Side, where they’re paying $3,000 a month. He saw his old apartment listed online for $4,500. It was off the market within two weeks, he said.

The legality of rent increases depends on the lease, whether the apartment has some rent controls and the market rate, said Erin Evers, a staff attorney in the housing unit of Legal Services NYC. In market-rate apartments, New York landlords can raise the rent as much as they want, she said.

“There’s not a lot that the tenant can do,” Evers said. She urged tenants to look into whether their apartment is rent-stabilized, even if they signed a market-rate lease, by requesting the rent history of the building through New York state’s Homes and Community Renewal agency.

It’s especially tough for new tenants. Landlords have to give 90 days’ warning before raising the rent by more than 5% to tenants who have lived in an apartment for two years or more, said Andrea Shapiro, director of program and advocacy at the Metropolitan Council on Housing. It’s only 30 days for tenants renewing after a year.

Brandon Himes, a 25-year-old flight attendant, moved back to New York City last year after living at home in Phoenix while furloughed. He found a two-bedroom, one-bathroom apartment in the East Village and signed a lease last November for $1,700 — a steal for the location. His upcoming renewal price for this November is $2,900 — about a 70% increase. His landlord didn’t explain why.

He negotiated that down to $2,600, still a more than 50% increase. He can technically afford the rent, but he’ll be trimming in other areas. “Since I’m a flight attendant, I’m going to have to cut back on eating out in other cities,” he said. “Normally when I’m at a hotel, I order food or go out, but I’m probably going to have to pack my own meals.”

Alex Tracy, 32, and his boyfriend found a two-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn last year for $2,000 a month, but the landlord only offered a nine-month lease. Then in late June, he got an automated email informing him of a 50% rent increase to $3,000.

“We looked at the history of the apartment and I don’t think it ever approached this much,” Tracy said. “There is no justification for this at all.”

Tracy negotiated and got two months for free — effectively paying $2,500 a month over a 12-month lease.

Finding another apartment on such short notice would have been difficult and stressful, he said.

Brooklyn was the only borough where median asking rent prices have recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Rental discounts were also the rarest in Brooklyn, where only 8.7% of rentals were discounted in July, the lowest share of all boroughs analyzed by StreetEasy. Greenpoint was the Brooklyn neighborhood with the highest year-over-year increase in asking rents.

When the Dime, a luxury development in Williamsburg, opened for leasing in May, it offered as many as three free months for 15-month leases, as well as complimentary parking, which normally cost $200 a month, according to Tanner McAuley, who managed it until recently.

Now, new tenants are offered one month free on a 12-month lease — but those who are renewing get nothing. Current tenants are hesitant to leave, given the state of the market, said McAuley, a leasing director with Douglas Elliman.

People who try to move are having a hard time finding a new place, as inventory across all boroughs dwindles. In July, inventory had fallen 43% from a year earlier, according to StreetEasy.

On the plus side, landlords by and large are still paying brokers’ fees — an incentive to attract tenants — which often equal a month’s rent or more, taking away a significant potential cost to moving and making it more likely that a landlord would want to keep a tenant. In July, 74% of rentals on StreetEasy were advertised as “no-fee,” a number that’s remained the same since last year.

Apartment hunting feels much different this year. In July, 9.1% of rental listings citywide had been discounted, compared with 29.1% a year earlier and 15.6% in July 2019, according to data from StreetEasy.

Those who are able to snatch apartments are hoping to keep them for longer. Nearly 60% of Manhattan apartments rented in May went to tenants who signed two-year leases, according to a June report by appraiser Miller Samuel Inc. and brokerage Douglas Elliman Real Estate.

Sarah Minton, an agent at Warburg Realty, said she expects the market to cool off going into the fall. The mad rush from newly vaccinated tenants trying to settle back into the city will have steadied and the return to the office may have slowed down by the Delta variant.

That’s what Claire Smith, a 24-year-old blogger and freelance social media manager, is banking on as she looks for a new apartment.

Smith moved to New York from Los Angeles in November, partially because she could afford rent. At the time she found a newly renovated two-bedroom in the West Village, one of Manhattan’s most expensive neighborhoods, for $3,500.

With one month free, that meant her out-of-pocket costs were more like $3,200 a month. In the lease renewal, her landlord offered a new price of $4,000.

“I’m hoping that things start looking a little bit better mid-October,” Smith said. “I have nothing set in stone — except for the fact that I’m moving out.”

Updated: 9-24-2021

How Los Angeles Became The City of Dingbats

The colorful carport-equipped apartment buildings offered affordable — and sometimes stylish — digs for generations of L.A. dreamers.

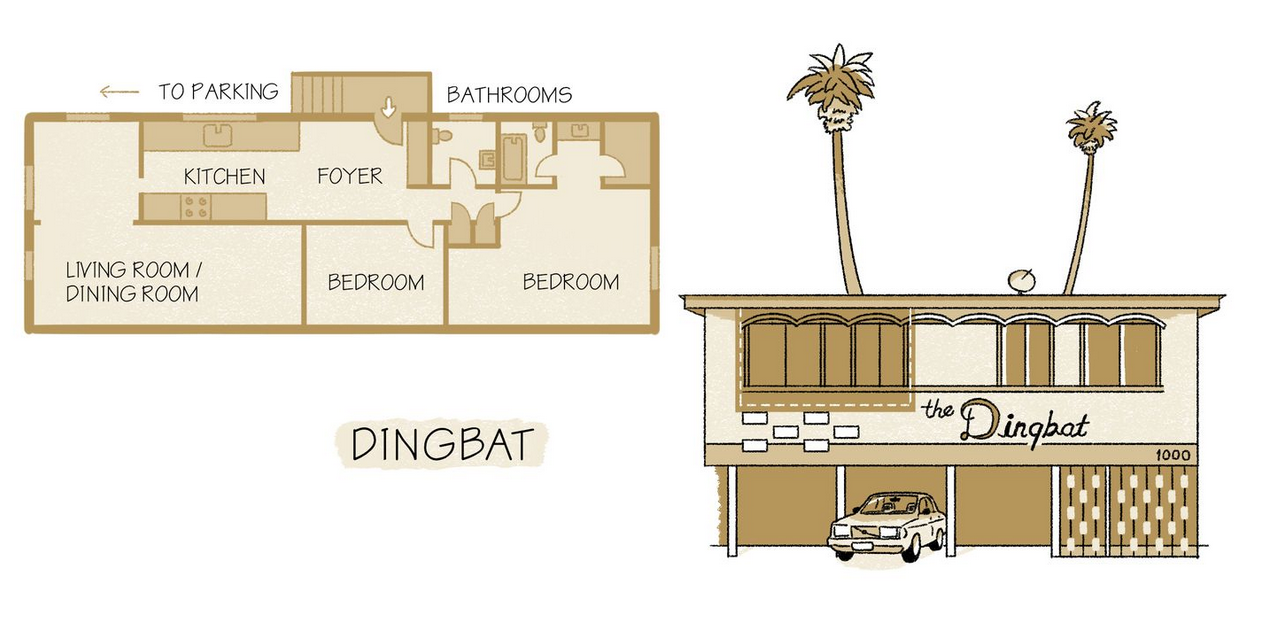

Faced with a housing shortage, Los Angeles once had a solution. From the San Fernando Valley to Culver City to La Cienega Heights, developers in the 1950s and ’60s tore down thousands of older buildings and filled in virtually every square foot with aggressively economical two- or three-story apartment complexes — known locally as dingbats.

Subdivided into as many units as the lots could accommodate — usually between 6 and 12 — most of these stucco boxes left little room outdoors, except for an exposed carport slung beneath the second floor. This new format for affordable multifamily living became nearly as ubiquitous as the single-family tract housing that iconified the much-mythologized Southern California suburban lifestyle.

British architecture critic Reyner Banham popularized the term, which both captures the buildings’ somewhat addled appearance and riffs on the ornamental glyphs used by typesetters. But dingbats did provide an essential resource for a growing city: Los Angeles County added more than three million residents between 1940 and 1960, thanks to job booms in manufacturing and aerospace, educational opportunities for returning GIs, and the lure of year-round sunshine.

Construction raced to keep up, with more than 700,000 housing units built countywide in the 1950s. New highways allowed much of this growth to sprawl into the suburbs: Vast numbers of cookie-cutter homes replaced citrus groves and ranchlands, sold as one’s own little slice of Elysian movieland, complete with driveway and pool.

Dingbats were a multifamily answer to that single-family template: Often built by small developers and mom-and-pop property owners who lived in the back, they were designed to house single people, young couples, and other upwardly mobile new residents, of which there were many. They also uniquely captured the mix of sun-drenched fantasy and hard-edged reality that remains integral to the city’s essence — after all, no place can stay a paradise forever when you actually live there.

In his path-breaking 1971 appraisal of Southland urbanism, Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, Banham called them “the true symptom of Los Angeles’ urban Id, trying to cope with the unprecedented appearance of residential densities too high to be subsumed within the illusions of homestead living.” Now, as 21st-century problems call for revising that suburban dream, the dingbat holds timely lessons within its stucco walls.

The first of those lessons might be that aesthetics aren’t everything. Invariably rectangular, flat-edged, and built of the cheapest materials, dingbats are unapologetically utilitarian. Yet they are anything but blank-faced. Many prominently display a single ornament, such as a starburst or boomerang, or feature decorative trimmings with a Tiki, French Chateau, or Space Age aesthetic.

Pastel paint jobs are common, as are aspirational building names splayed on giant signage legible from passing cars. Such affectations could be seen as mirroring the city’s reputation — fair or not — as a land of artifice.

“They’re stylistically diverse with exotic names, but they present as what they aren’t,” said Thurman Grant, co-editor of Dingbat 2.0: The Iconic Los Angeles Apartment as Projection of a Metropolis. “Which is literally a dumb box with as many units packed in as possible, with a slapped-on facade.”

The emphasis on efficiency does not stop once inside. Little space is wasted on interior walkways or common areas, though some have small courtyards or in rare cases, swimming pools. Units usually are one or two bedrooms, with truncated hallways and kitchen areas that open up to living-dining rooms. Apartment layouts vary depending on where space was available.

“You get a lot of weird, L-shaped configurations to squeeze in stuff around the carport,” said Joshua Stein, co-editor of Dingbat 2.0. “Or sometimes the carports themselves couldn’t be full-width.” That often meant poor airflow and thin walls and ceilings.

Many Angelenos considered these new constructions a visual blight, and still do. Before Banham, the dingbat moniker was already in use as a pejorative, including in reference to low-quality, ugly construction. California historian Leonard Pitt once wrote that “the dingbat typifies Los Angeles apartment building architecture at its worst.”

Yet like a species that adapts to its environment, dingbats were a response to the demands of their moment. City zoning codes required only one vehicle space per housing unit of more than three habitable rooms, which allowed for the dingbat’s relatively modest parking footprint at grade level (this would change after increased parking minimums and other development restrictions made dingbats less economical to build, as the architectural historian Steven Treffers has noted).