Ultimate Resource Covering US Oil, Gas And Shale Industry (#GotBitcoin)

Smaller drillers, which account for sizable part of U.S. oil production, are struggling to pay off hefty debt burdens. Ultimate Resource Covering US Oil, Gas And Shale Industry (#GotBitcoin)

Bankruptcies are rising in the U.S. oil patch as Wall Street’s disaffection with shale companies reverberates through the industry.

Twenty-six U.S. oil-and-gas producers including Sanchez Energy Corp. and Halcón Resources Corp. have filed for bankruptcy this year, according to an August report by the law firm Haynes & Boone LLP. That nearly matches the 28 producer bankruptcies in all of 2018, and the number is expected to rise as companies face mounting debt maturities.

Energy companies with junk-rated bonds were defaulting at a rate of 5.7% as of August, according to Fitch Ratings, the highest level since 2017. The metric is considered a key indicator of the industry’s financial stress.

The pressures are due to companies struggling to service debt and secure new funding, as investors question the shale business model.

Many drillers financed production growth by becoming deeply indebted, betting that higher oil prices would sustain them. But investor interest has faded after years of meager returns, and some companies are struggling to meet their obligations as oil prices hover below $60 a barrel.

Private companies and smaller public drillers have been hit hardest so far. Those producers collectively generate a large portion of U.S. oil, according to consulting firm RS Energy Group, and their distress reflects issues affecting all U.S. shale.

“They were able to hang in there for a while, but now their debt levels are just too high and they’re going to have to take their medicine,” said Patrick Hughes, a partner at Haynes & Boone.

Halcón Resources filed for bankruptcy protection in August, three years after its last trip through bankruptcy court, as it contended with a production slowdown in West Texas and higher-than-expected gas-processing costs.

Halcón’s chief restructuring officer, Albert Conly of FTI Consulting Inc., said in a court filing that those challenges led the company to become more highly leveraged, which violated the loan covenant on its reserve-backed loan. That prompted lenders to cut Halcón’s credit line by $50 million earlier this year, Mr. Conly said.

Sanchez Energy filed for bankruptcy protection Aug. 11, citing falling energy prices and a dispute with Blackstone Group Inc. over assets they had jointly acquired from Anadarko Petroleum Corp. in Texas’ Eagle Ford drilling region in 2017. Blackstone claimed Sanchez defaulted on a joint deal to develop the assets, and that it was entitled to take them over, which Sanchez disputed.

Other shale drillers have recently missed key debt payments, and could be forced into bankruptcy.

EP Energy Corp. missed a $40 million interest payment due Aug. 15 as it struggled under the weight of debt it took on to help private-equity investors including Apollo Global Management LLC buy the company in 2012.

As of the second quarter, the Houston-based driller’s total debt was six times its earnings, excluding interest, taxes and other accounting items, according to S&P Global Market Intelligence, well above the level at which lenders generally consider loans to be troubled.

The company has said in securities filings that it has until mid-September to make its interest payment, and it is considering a range of options that include filing for bankruptcy protection.

Unlike several years ago, the current round of bankruptcies isn’t driven by a collapse in crude prices. The U.S. benchmark oil price has roughly doubled since 2016, when crude bottomed out below $30 a barrel. That year, 70 U.S. and Canadian oil-and-gas companies filed for bankruptcy, according to Haynes & Boone.

The current financial strain on shale producers is likely to intensify as many companies that took on debt after the 2016 oil slump face large debt maturities in the next four years. As of July, about $9 billion was set to mature throughout the remainder of 2019, but about $137 billion will be due between 2020 and 2022, according to S&P.

The debt of Houston-based Alta Mesa Resources Inc. is among the riskiest U.S. bonds, according to Fitch. Initially handed a $1 billion blank check by investors to invest in shale, the company said earlier this year its future is in question.

“A lot of companies are highly levered and facing maturities on their debt that I like to call a murderer’s row, maturities are coming year after year,” said Paul Harvey, credit analyst at S&P.

That could spur a race to refinance, but many energy bonds are pricing higher. A metric that measures the lowest possible yield an investor can earn on a bond without the issuer defaulting was more than 7% in July for oil and gas bonds, compared to about 4% for the overall corporate market, according to S&P. For oil and gas bonds considered junk, such yields were nearly 13%.

Energy is the largest sector of the high-yield market, but companies have backed away as the cost of capital has increased. As of July, this year’s energy high-yield issuances had fallen 40% from the same period a year earlier, while overall corporate high-yield issuances rose 32%, according to Fitch Ratings.

“Any available capital structure is going to be more expensive than it was a year ago,” said Tim Polvado, the head of U.S. energy for the Paris-based bank Natixis SA.

As is often the case in corporate bankruptcies, many equity holders might be all but wiped out while bondholders emerge as the owners of reorganized shale companies.

Senior bondholders in Houston-based Vanguard Natural Resources LLC traded about $433 million in debt for nearly all of the equity of the reorganized company, now named Grizzly Energy LLC, after the firm filed for bankruptcy earlier this year. The company’s Class C shares trade for a penny each.

Updated: 12-2-2019

Brent Oil Set To Disappear As Crude-Price Benchmark Lives On

Royal Dutch Shell is set to plug its last remaining Brent oil wells in the North Sea next year.

The world’s most famous oil and gas field—and the backbone of global crude pricing—has dried up. Soon the Brent benchmark will have no Brent oil.

Royal Dutch Shell PLC is expected next year to plug the last remaining Brent oil wells, located in the North Sea’s East Shetland Basin, about 115 miles northeast of Scotland’s Shetland Islands. The closures mark the end of an era, as the industry shifts its focus to smaller oil finds near existing infrastructure.

Many companies are shutting down platforms above massive fields discovered in the 1970s, but Brent stands apart as one of the first and most significant of these finds. The field has generated billions of dollars for Shell, its partner in the field, Exxon Mobil Corp. and the U.K. government.

In the late 1980s, Brent crude became the benchmark on which most of the world’s oil is priced and is still used to set the price of the multi-trillion dollar Intercontinental Exchange Brent futures market.

“The role it has played is a cornerstone for this industry now for 40 plus years,” said Steve Phimister, vice president of upstream and director of U.K. operations at Shell.

The Brent benchmark will keep its name and increasingly represents a blend of North Sea crudes, with the potential to include oil from other locations in the future.

Shell discovered the field in 1971 and named it after the brent goose, keeping with the seabird theme the company used for naming its discoveries at the time. Developing it was a huge and expensive undertaking. Standing as tall as the Eiffel tower, Brent Charlie, the last active platform of Brent’s original four, was built to withstand some of the most hostile conditions on earth.

The North Sea’s wave heights of up to 12 meters and gale-force winds of up to 100 miles an hour make it a place for “hardy individuals,” said Aberdeen-based Alan Lawrie, who joined Shell in 1984 when he was 16 years old. Now 51 and manager of Shell’s Charlie platform, he said Brent was the field everyone vied to work on.

Like all of the approximately 180 workers on the platform, Mr. Lawrie is on a fly-in fly-out rotation, spending two weeks offshore at a time and working 12-hour shifts while there. The Charlie platform can house up to 192 people in what is like a miniature village on an island in the middle of nowhere. It has restaurants, games rooms and a gym—where Mr. Lawrie has spent much of his downtime on a rowing machine.

One of his fondest memories is celebrating his 21st birthday on Charlie with his colleagues, who teased him with a gift of an 18-inch model wooden oar that one of them had whittled between shifts on the platform.

The North Sea oil rush was helped by higher oil prices after the Arab Oil Embargo in the early 1970s, when crude prices quadrupled. Oil got another jolt from shortages caused by the Iranian Revolution in 1979.

“We were importing all our oil and the main emphasis from the U.K. government, and oil companies was to get to first oil as quickly as possible, to help our balance of payments, which was suffering badly because of a huge bill for paying for oil imports,” says Alex Kemp, professor of petroleum economics at the University of Aberdeen Business School.

The project was risky and had massive cost overruns, as the North Sea was a frontier region, and the effort used new technologies to go deeper underwater than ever before and drill more than 4 miles beneath the seabed.

North Sea oil production has been in decline since the turn of the century, partly because it was too expensive to compete with other regions. At its peak in 1982 Brent produced more than 500,000 barrels a day, enough to meet the annual energy needs of around half of all U.K. homes at the time. The U.K. region of the North Sea produced around 1.8 million barrels a day of oil and gas last year, less than half the peak hit in 1999.

As Brent production declined, several other oil grades were added to what is now a basket of North Sea crudes used to set the Brent price. Still, production of the grades used to price Brent is expected to drop by half—to 500,000 barrels a day—by 2025 because of a lack of investment and fields winding down.

The Brent benchmark’s main competitor, U.S. West Texas Intermediate, is backed by much higher volumes of crude. Around 4 million barrels a day of U.S. crude, which represents around 4% of global production, meets the quality requirements needed for delivery against WTI futures.

Some researchers, including the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, believe that the Brent benchmark could eventually include U.S. crude to set the price.

Meanwhile, Shell is set to decommission the Charlie platform sometime next year. “There’s a tear in your eye when we’re removing the big ones,” says Shell’s Mr. Lawrie, referring to the platforms. “But it’s a natural part of the life-cycle of the industry we work in.”

Updated: 3-16-2020

After A Long Fall In Oil Prices, A Crash

Oil’s plunge has eroded hundreds of billions of dollars in market value from producers globally, fueled speculation about bankruptcies and mergers.

For Rebecca Babin, the oil crash arrived slowly, then all at once.

The senior energy trader at CIBC Private Wealth Management watched crude prices fall 10% March 6 after Saudi Arabia couldn’t convince Russia to join a plan for deeper supply cuts. The next day’s escalation in the feud sent the 42-year-old scrambling to alert her team, adjust their models and prepare for the opening of trading Sunday evening.

When trading began, U.S. crude oil tumbled from $41 a barrel to around $30 in a matter of minutes, going on to post its biggest one-day drop since the first Gulf War in 1991. Ms. Babin said she woke up every two hours Sunday night to stay abreast of the turmoil, which now has investors who rode out oil’s spike to $145 in 2008 preparing for one of the world’s key commodities to trade at a fraction of that price moving forward.

“There were elements of it that were unlike anything I’ve experienced,” she said. “This is clearly a change to how the commodity is going to trade for the foreseeable future.”

Oil went on to swing wildly in the low $30s in another turbulent week in global markets, ending the week at $31.73. Its plunge has eroded hundreds of billions of dollars in market value from producers around the world and fueled speculation about bankruptcies and mergers. Skepticism about energy companies’ ability to pay a heavy debt burden is also driving concerns that oil’s fall will hurt lenders and exacerbate the economic slowdown resulting from the coronavirus.

While consumers are enjoying the lowest fuel prices in years, analysts say it is too early to count on a demand boost from the energy crash. Companies are already reducing spending, and the transportation restrictions resulting from the coronavirus will likely dull the typical increase in travel one would expect with fuel costs dropping. Research firm Capital Economics projects the drop in drilling investment to more than offset the boost in gasoline consumption in calculating second-quarter U.S. economic growth.

For Americans who lived through the oil-price spikes of 1973 following the Arab oil embargo, 1979 after the Iranian revolution and the 1990 Gulf crisis, the concept of slumping crude being a negative economic signal seems perplexing. Many remember gasoline shortages snarling transportation and the oil-price spike above a record $145 in July 2008 that preceded the financial crisis.

Since then, horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing techniques spurred a historic production boom that made the energy industry an integral part of the U.S. economy and supported states from Texas to North Dakota. Soaring shale output powered the U.S. ahead of Russia and Saudi Arabia to become the world’s largest producer of oil and gas.

Banks lent heavily to energy producers, helping many survive the sector’s last major downturn after Saudi Arabia cut prices in 2014 to challenge the shale boom. Oil companies are a key chunk of the high-yield bond market, meaning many investors fear a wave of defaults and bankruptcies that could contribute to further market stress.

“It’s an oil crisis upside down,” said Regina Mayor, who leads KPMG LLP’s energy practice. “My clients are trying not to panic…. It’s a drive to the bottom, and it’s not good for anyone.”

Saudi Aramco slashed most of its prices recently by $6 to $8 a barrel, and Saudi officials have said the kingdom plans to increase output. The move came after Russia refused to accept deeper supply curbs at a meeting earlier this month in Vienna. The Wall Street Journal reported that Saudi pleas for deeper cuts alienated both Russian President Vladimir Putin and his energy minister Alexander Novak.

The clash is an unprecedented shift because supply is expected to increase significantly during a sizable demand drop. After the two nations coordinated oil supply as part of a price-stabilizing alliance between the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and other nations starting in 2016, their shift to a price war focused on market share threatens to amplify pressure on global growth.

“We’re at a different way of looking at things,” said Darwei Kung, head of commodities and portfolio manager at DWS Group. “We’re cautious in terms of our positioning.”

Companies including Occidental Petroleum Corp., Marathon Oil Corp., Diamondback Energy Inc. and Apache Corp. have pledged to curb spending in response to the splintering of the Saudi-Russia alliance. Billionaire shareholder activist Carl Icahn has bought more Occidental shares as they plummet, doubling down on his fight to take control of the embattled company, The Wall Street Journal reported.

Shares of S&P 500 energy companies recently hit their lowest level in more than 15 years, while Exxon Mobil Corp. and Chevron Corp. have together lost about $200 billion in market value already this year.

The industry’s latest challenge also reflects sudden investor skepticism that institutions from OPEC to governments and central banks can keep the economy balanced in response to the coronavirus. Entering the year, most Wall Street analysts expected oil to stay in its longstanding trading range, projecting U.S. crude between about $50 and $60.

As hedge funds and other speculative investors increased wagers on rising prices, they hit a peak above $63 on Jan. 6 after a U.S. airstrike killed a high-ranking Iranian military leader.

In the two months since then, they have been sliced nearly in half, leading cascading declines across global markets. The S&P 500 is in bear-market territory, defined as a drop of 20% from a recent peak, and on Thursday ended an 11-year bull-market run that drove the index up about 300%.

Meanwhile, the yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note, which affects everything from auto loans to mortgage debt, tumbled to a record low of 0.5% last Monday from 1.91% at the end of last year. It ended the week at 0.95%. Those moves in tandem with tumbling raw-materials prices are sending a worrying economic signal to many investors.

“Oil declining dramatically is a telltale sign that the industrial economy is in trouble,” said Gary Ross, chief executive of Black Gold Investors LLC and founder of consulting firm PIRA Energy Group.

This week’s latest market malaise began last Sunday evening when oil-futures trading began at 6 p.m. ET. Prices fell around $30 a barrel before trimming some of that slide, but the damage quickly began rippling across asset classes. U.S. stocks fell hard enough at the open Monday morning to trigger a circuit breaker for the first time in 23 years that kept trading frozen for 15 minutes.

“Nobody was saying it was going to open at $30,” said Robert Yawger, director of the futures division at Mizuho Securities U.S.A. in New York. “It’s a nasty situation.”

Now, investors are weighing how much further oil prices can fall. U.S. crude fell to $26 in February 2016 before recovering as the Chinese economic outlook improved and OPEC cut supply. Four years later, analysts say they are struggling to find a similar solution.

“I couldn’t think of anybody who warned of this,” said Gene McGillian, vice president of research at Tradition Energy in Stamford, Conn. “The world, if it wasn’t for the production agreement, is awash in oil.”

Rob Thummel, a senior portfolio manager at Leawood, Kan.-based investment firm Tortoise, said he still thinks prices will recover in the long term because large producers need them to support their economies. But the OPEC surprise has him bracing for more big swings for now.

“It’s a complete shock to everyone,” he said. “This is all fear and anxiety.”

Updated: 3-16-2020

Oil Crash Is Bad News for Regional Banks That Went Big on Energy

Problems of energy companies could be passed on to their lenders.

Lenders are bracing for loan losses and depressed earnings from an oil crash that is bruising the North American energy industry.

U.S. and Canadian banks have more than $100 billion in loans outstanding to energy companies. An oil-price crash set in motion by Saudi Arabia earlier this month could cause many of those energy companies to struggle to make good on those loans.

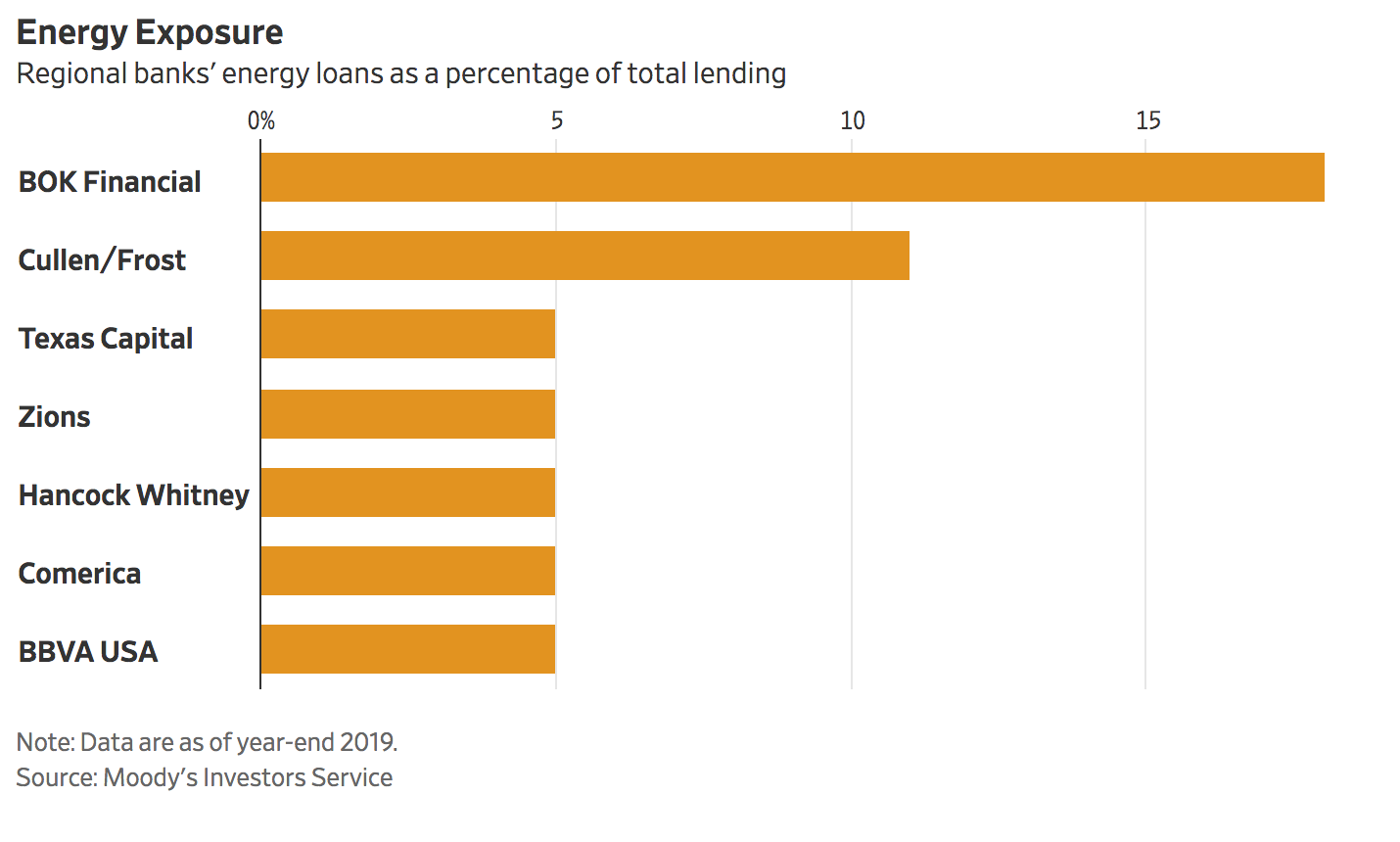

Especially vulnerable are regional banks with big energy-lending portfolios. Larger banks also are on the hook for billions of dollars in loans to the energy industry, but they are relatively less exposed because their balance sheets are much bigger and their lending businesses more diversified. Energy accounts for 3.2% of Citigroup Inc.’s loan portfolio and 2.1% of JPMorgan Chase & Co.’s loan book, according to Goldman Sachs analysts.

But a shakeout among regional banks’ borrowers could dent their earnings this year between an average of 15% to 60%, depending on the extent of loan losses, said Keefe, Bruyette & Woods analyst Brady Gailey.

“It is a big deal for these oil-exposed banks,” he said.

U.S. benchmark prices ended the week at $31.73. a barrel, 23% below their level on March 6.

Prices still have a long way to fall to match the extended decline between 2014 and 2016, when prices for the benchmark West Texas Intermediate grade fell to $26 a barrel from $106. That decline battered the stocks of energy lenders and forced them to increase their credit reserves to guard against defaults.

A spate of energy companies filed for bankruptcy during the last crash to pare their debt; in the years since, they have piled it back on. In addition to their bank loans, North American oil and gas exploration and production companies have “a staggering” $86 billion of rated debt coming due between 2020 and 2024, Moody’s Investors Service said in a February report.

Those lofty debt levels could become a big problem if prices stay low for a while, leading to a new round of defaults and bankruptcy filings that could result in loan losses.

Bank investors are expecting fallout. The KBW Nasdaq Regional Banking Index has fallen almost 14% since March 6, just before Saudi Arabia launched the oil-price war. While much of that decline can be traced to the broader market rout, banks with the biggest relative exposures to the energy industry have fallen even more. Some have lost a quarter of their market value since the March 6 close.

Bank of Oklahoma parent BOK Financial Corp. is among them. Loans to energy companies such as deeply indebted Whiting Petroleum Corp. account for some 18% of its lending book. The bank’s shares have fallen 22% from March 6 through Friday’s close.

The bank should be able to weather the rout in the short term, BOK chief financial officer Steven Nell said Tuesday in a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. The outlook is cloudier if oil prices stay low for a year or longer.

“At that point, we would be more likely to see loss content in the portfolio and a greater impact on the overall economy, and in turn lower loan demand,” Mr. Nell said in the filing.

Cullen/Frost Bankers Inc. has reduced its exposure to energy borrowers since 2015, during the last big plunge in energy prices. Still, 11% of the San Antonio-based bank’s loan portfolio was dedicated to energy companies at the end of 2019.

The bank reported a more than 50% increase in problem energy loans in the fourth quarter from the third. In January, before prices crashed, CEO Phillip Green said the bank expected higher charge-offs in the sector later this year. The bank’s stock fell almost 10% through Friday. A bank spokesman said the bank was confident in its lending standards. “We’ve been through worse things than this before,” he said.

The energy industry will face a reckoning in the spring, when banks embark on their twice-yearly reassessment of the value of the oil and gas reserves that serve as collateral for their loans.

These loans were last evaluated in the fall, when crude prices were above $50 a barrel. If prices remain in the $30s or keep falling, much of the oil won’t be economical to extract, meaning companies can no longer borrow against it and must repay banks.

For energy companies already struggling with big debt burdens and shrinking cash flows, a bank’s sudden demand for repayment or a reduction in their borrowing capacity can set off a spiral into default.

The borrowing-base redeterminations, as they are known, could pose a problem for banks like Dallas-based Comerica Inc. The bank has reduced the size of its energy portfolio by $1.3 billion since 2015; energy loans now account for 4.5% of its loan book, said CEO Curtis Farmer at a banking conference on Tuesday. Still, should prices stay low, its borrowers could lose access to credit.

“The ultimate outcome will depend on the duration of the cycle,” Mr. Farmer said.

Losses of 5% in its energy portfolio could depress Comerica’s 2020 earnings per share by 9%, according to KBW. A spokesman said the bank lost an average 1.5% per year in its energy loan book between 2015 and 2017.

Updated: 4-1-2020

Trump To Meet With Oil CEOs About Helping Industry

Steep oil-price drop has U.S. industry reeling.

President Trump is set to meet Friday with the heads of some of the largest U.S. oil companies to discuss government measures to help the industry weather an unprecedented oil crash, people familiar with the matter said.

The meeting is to take place at the White House and will include Exxon Mobil Corp. Chief Executive Darren Woods, Chevron Corp. Chief Executive Mike Wirth, Occidental Petroleum Corp. Chief Executive Vicki Hollub and Harold Hamm, executive chairman of Continental Resources Inc., the people said.

The U.S. oil and gas industry has been pummeled recently by the dual shock of plummeting oil demand because of the coronavirus pandemic and surging supply as Russia and Saudi Arabia are locked in a price war and flood the market with crude.

Oil prices plunged this week to just above $20 a barrel, the lowest level in nearly two decades.

Mr. Trump and the executives are set to discuss potential aid to the industry, including tariffs on oil imports into the U.S. from Saudi Arabia, and a waiver of a law that requires American vessels be used to transport goods, including oil, between U.S. ports, according to two of the people.

But the oil industry isn’t unified in its support for some of the measures, the people familiar with the matter said. Only Mr. Hamm supports oil tariffs, according to the people. A temporary waiver of the Jones Act, which would allow U.S. ships to transport oil around the country, could represent a compromise and earn the backing of the other companies, one of the people said.

Such a waiver would allow U.S. oil to be shipped from the petrochemical hub on the Gulf Coast to markets on the East Coast and Washington state, which are currently being flooded with imports from Saudi Arabia. The U.S. has previously granted such waivers, typically for about 10 days, during other emergencies.

Updated: 4-1-2020

Whiting Petroleum Becomes First Major Shale Bankruptcy As Oil Prices Drop

The filing comes as many U.S. oil drillers face pressure to meet hefty debt obligations.

U.S. shale driller Whiting Petroleum Corp. filed for bankruptcy protection on Wednesday, becoming the first sizable fracking company to succumb to the crash in oil prices.

Whiting’s bankruptcy filing comes as many U.S. oil drillers face pressure to meet hefty debt obligations they took out from banks and bondholders to make America into the world’s largest oil and gas producer, as U.S. benchmark crude prices drop to their lowest levels in nearly two decades.

Oil prices are coming off their largest monthly drop ever as the coronavirus pandemic saps oil demand at the same time Saudi Arabia presses a price war against Russia by flooding global markets with crude. The price deterioration has pushed many U.S. shale companies to the brink of bankruptcy and upended efforts by those already in chapter 11 to restructure their operations.

If the downturn persists, a number of U.S. drillers could default on more than $32 billion of high-yield debt over this year, with a projected default rate of 17%, according to credit-ratings firm Fitch Ratings. Before crude tanked, Fitch had forecast a 7% default rate for 2020.

Last year, 41 U.S. oil companies filed for bankruptcy protection in cases involving $11.7 billion in debt, according to Dallas law firm Haynes & Boone.

With U.S. crude trading at around $20 a barrel—down from above $60 a barrel in January—dozens of U.S. shale producers are at risk of breaching debt covenants as their ratios of debt to pretax earnings balloon to untenable levels. To make matters worse, equity and debt markets that recapitalized producers in the last downturn a few years ago have largely closed to U.S. oil companies after years of poor returns, said Shawn Reynolds, portfolio manager at investment manager VanEck.

“There’s hardly anything you can do,” outside of restructuring debt, Mr. Reynolds said.

Whiting sought chapter 11 protection in U.S. Bankruptcy Court in Houston, after some bondholders agreed to swap $2.2 billion in debt for a 97% equity stake in the reorganized company.

Whiting said it needed to file for bankruptcy in part over worries that the company’s borrowing capacity on a $1 billion loan would be cut.

In court on Wednesday, Whiting lawyer Brian Schartz said the company thought the borrowing base wouldn’t go “anywhere but down.” He said the company was still rounding up the required support from creditors for the debt-for-equity swap.

Bankruptcies in the U.S. oil patch are expected to gain momentum in the second quarter, accelerating as some drillers are forced to shut in production amid reduced oil demand and low available storage capacity, said Buddy Clark, a partner and co-chair of energy practice group at Haynes & Boone.

“It’s a dire situation for everyone,” Mr. Clark said, noting that even bankruptcy courts are struggling to operate amid the pandemic and are under pressure from an influx of new cases. “It’s a weird dynamic, but people will want to get into bankruptcy quickly in order to beat the rush.”

A number of oil-and-gas companies, including Chesapeake Energy Corp., Ultra Petroleum Corp. and California Resources Corp., have either warned they may not stay current on their debts or hired restructuring advisers to negotiate with creditors.

Denver-based Whiting, one of the largest drillers in North Dakota’s Bakken Shale, had come under financial pressure even before U.S. crude prices collapsed.

Chief Executive Brad Holly said the company’s proposed restructuring was its “best path forward” given uncertainty about how long the Saudi-Russia price war and the coronavirus pandemic would go on.

Whiting foreshadowed its bankruptcy by taking steps on Friday to protect $3.4 billion in net operating losses, which are potentially valuable tax assets that could be used to reduce future federal taxes.

The company also drew down $650 million from its loan facility last week to generate cash and won’t make a $262 million debt payment that comes due Wednesday. The maturing bond has lost more than 90% of its value since mid-February, according to MarketAxess, and closed at 6 cents on the dollar on Wednesday.

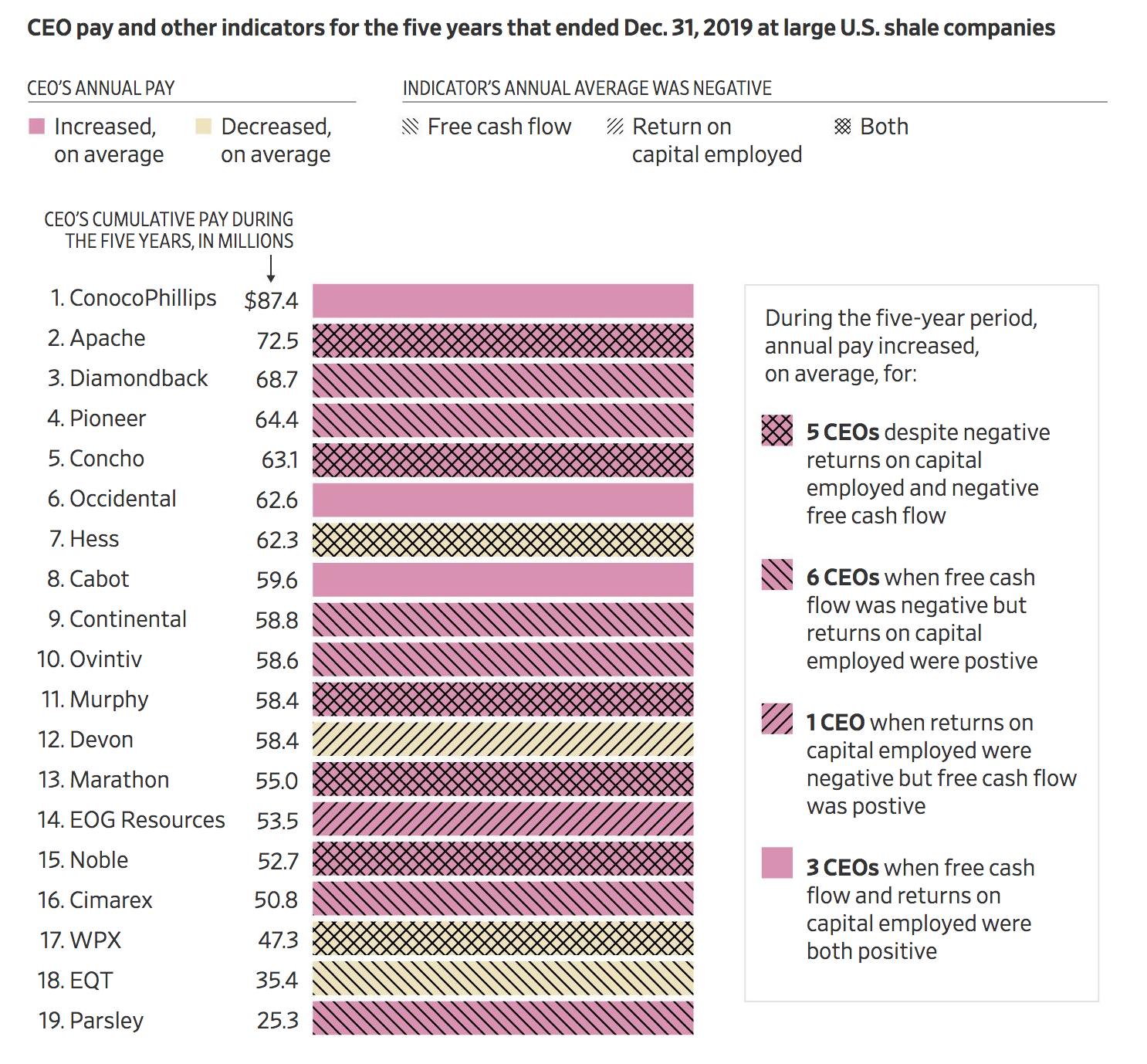

Before the bankruptcy, Whiting’s top five executives got board approval for $14.5 million in cash payments last week, including $6.4 million for Mr. Holly, according to a regulatory filing. The executives would be required to waive their participation in a previous bonus program and forfeit equity awards granted earlier this year.

Under Whiting’s restructuring proposal, top executives are in line to receive up to 8% of the stock in the reorganized company when it emerges from bankruptcy. Mr. Holly and other insiders together own less than 1% of the company, according to data from FactSet.

Updated: 4-13-2020

Baker Hughes Pursues $1.8 Billion Restructuring Plan Amid Oil-Price Declines

Oilfield-services company expects to book $15 billion in noncash goodwill impairment.

Baker Hughes Co. BKR 3.50% said it is pursuing a restructuring plan that will result in about $1.8 billion in charges and expects to book a roughly $15 billion goodwill impairment charge for the first quarter as the company faces the coronavirus pandemic and declines in oil and gas prices.

The oil-field services company said Monday it will book $1.5 billion of those charges for the first quarter. Future cash expenditures related to those charges are projected to be about $500 million with an expected payback within a year, it said.

Baker Hughes said it conducted an interim quantitative-impairment test as of March 31 due to uncertainty in oil demand and its effect on investment and operating plans of the company’s customers. The test concluded that the oilfield-services and oilfield-equipment reporting units’ carrying value exceeded their estimated fair value, resulting in a noncash goodwill impairment charge.

The company also said it plans to cut 2020 capital expenditures by more than 20%. It had $3 billion in cash and cash equivalents for the year ended Dec. 31, 2019.

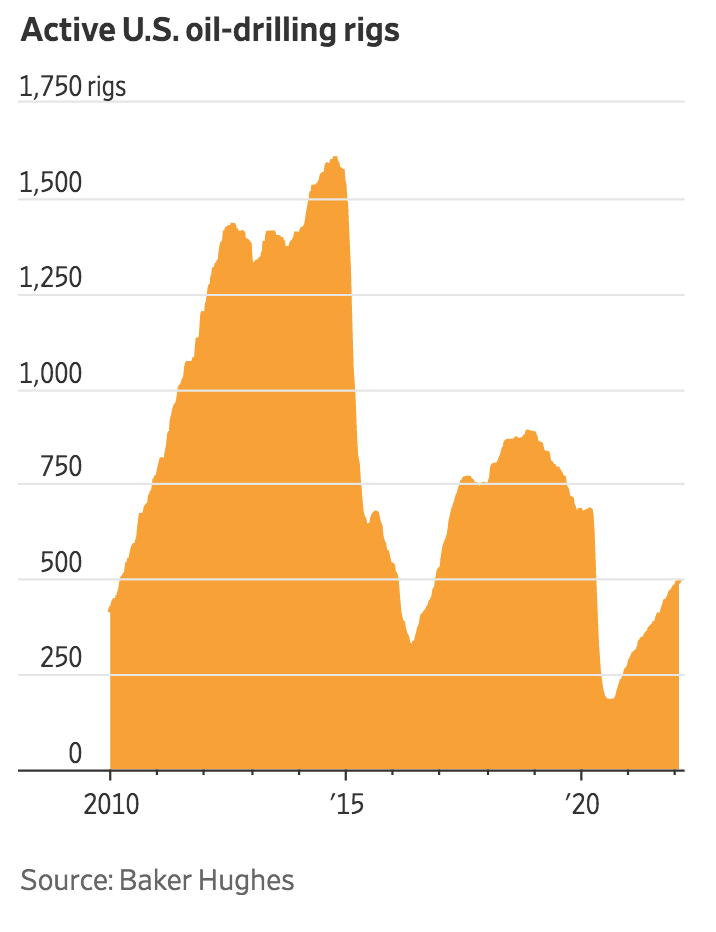

A standoff between Saudi Arabia and Russia over production cuts and a sharp drop in demand caused by the pandemic have led to a big decline in oil prices. The number of rigs drilling in the U.S. has fallen to about 600, down from nearly 800 a month ago, according to Baker Hughes.

After reducing its stake in 2019, General Electric Co. no longer controls Baker Hughes or counts its financial results or staff as its own.

Updated: 4-13-2020

North America’s Oil Industry Is Shutting Off the Spigot

Energy producers are resorting to the desperate measure of shutting in productive oil wells.

Canceled orders were mounting when Texland Petroleum LP recently decided to shut in each of its 1,211 oil wells to cease production by May.

“We’ve never done this before,” said Jim Wilkes, president of the 7,000-barrel-a-day Fort Worth, Texas, firm, which has weathered oil busts since 1973. “We’ve always been able to sell the oil, even at a crappy price.”

Now there are no buyers for the crude coming from its wells and no choice but to shut them in. Texland told state regulators its plans and applied for a loan through the Small Business Administration’s Paycheck Protection Program to keep its 73 employees on payroll.

From the West Texas desert, where oil is blasted from deep shale formations, to the wilds of western Canada, where multibillion-dollar steam plants bubble thick crude from the earth’s crust, energy producers are resorting to the desperate measure of shutting in productive wells.

Though President Trump promised the U.S. would curtail oil output in a pact with major producers, including Saudi Arabia and Russia, there is really no mechanism for the federal government to do so without legislation or major regulatory changes, such as tougher environmental enforcement. Instead, U.S. producers are choking back on their own due to the dismal economics and strained physics of the oil market.

The sharp drop in fuel consumption caused by the coronavirus pandemic and exacerbated by the feud between the world’s largest producers has limited options for North American oil companies. Pipelines, refiners and storage facilities are filling up. Even when there is somewhere to send oil, low prices mean that many barrels lose money.

West Texas Intermediate, the main U.S. price benchmark, closed Monday at $22.41 a barrel, down 63% since the start of the year. It has been even worse in Midland, Texas, where a lot of oil extracted from the Permian Basin is priced, and in western Canada, from which most of the country’s output comes. Oil has traded below $10 a barrel in both markets.

Since mid-March, producers ranging from Exxon Mobil Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell PLC to Oklahoma City’s Devon Energy Corp. and Cenovus Energy Inc. of Calgary, Alberta, collectively have announced spending cuts totaling some $50 billion.

The number of rigs drilling in the U.S. has fallen to about 600, down from nearly 800 a month ago, according to Baker Hughes Co. Drilling is always down in Canada this time of year, when the spring thaw hinders accessibility, but the 35 rigs operating there are the fewest Baker Hughes has ever counted.

It can take months for the flow from new wells to taper off, so production has only begun to reflect the austerity. U.S. production has declined about 5% from March’s record levels, according to the Energy Information Administration.

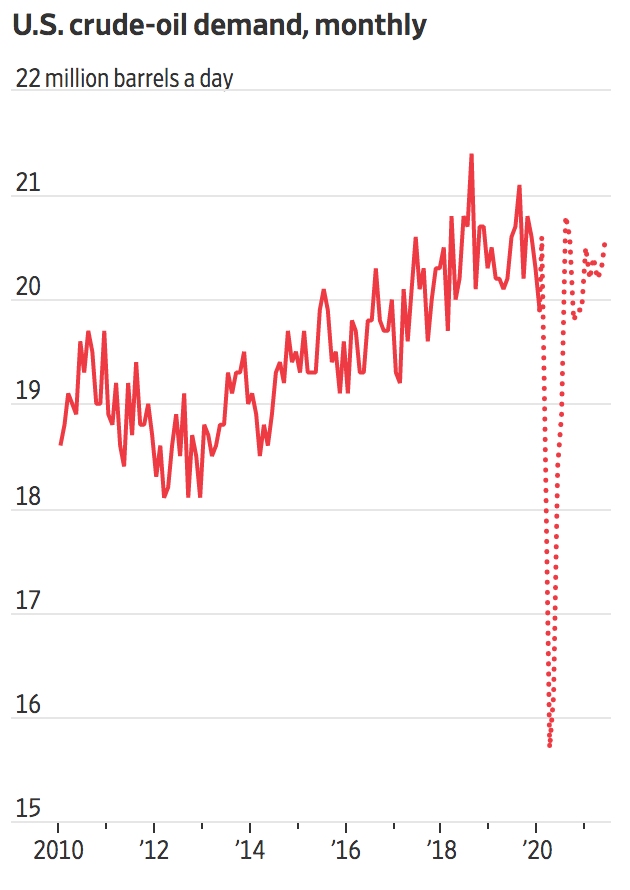

The drop in demand has been steeper, with factories idled, flights grounded and billions of people around the world under stay-at-home orders to fight the spread of the deadly virus. Analysts forecast oil consumption declining by at least 20 million barrels a day, representing roughly 20% of global demand.

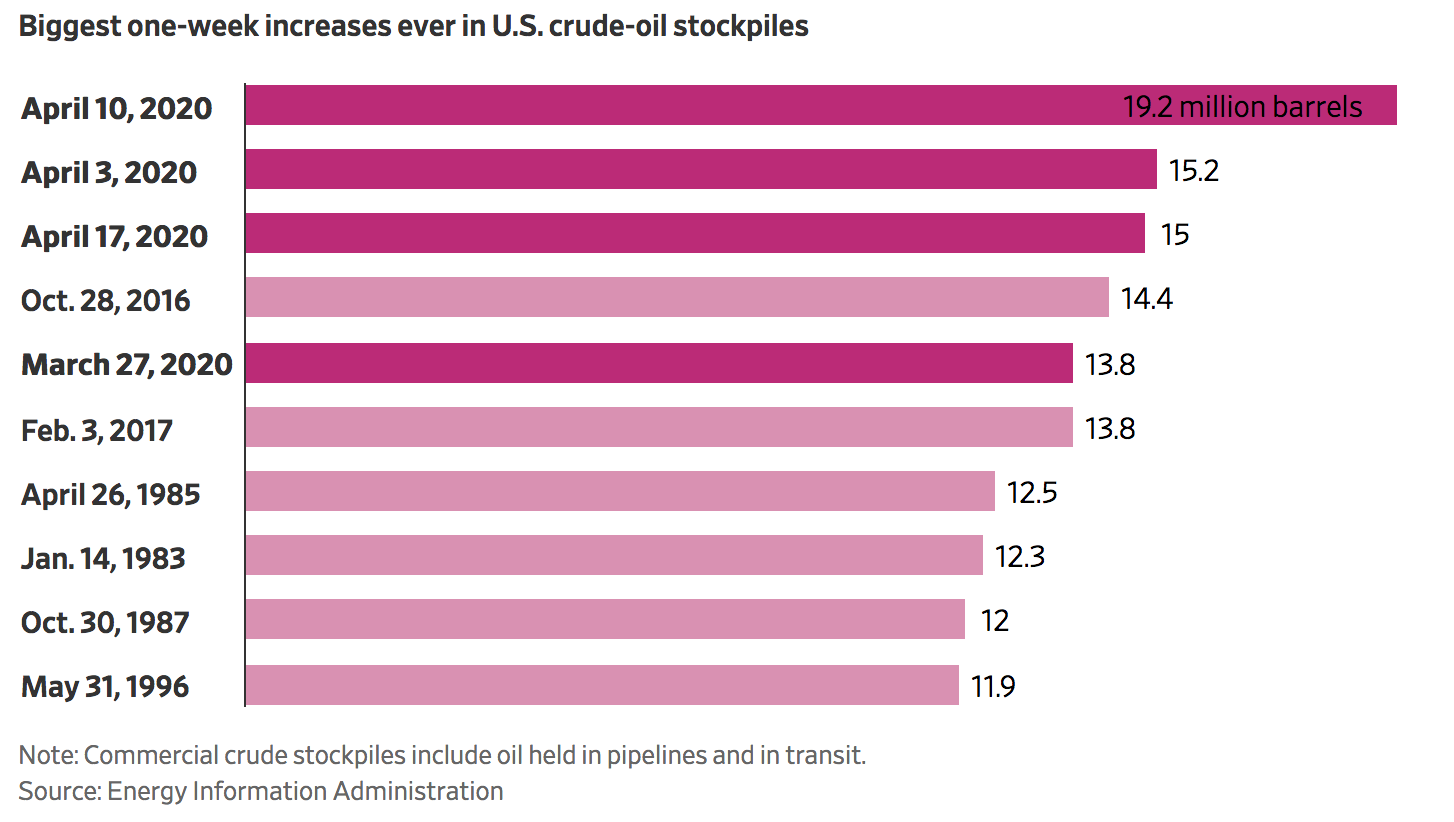

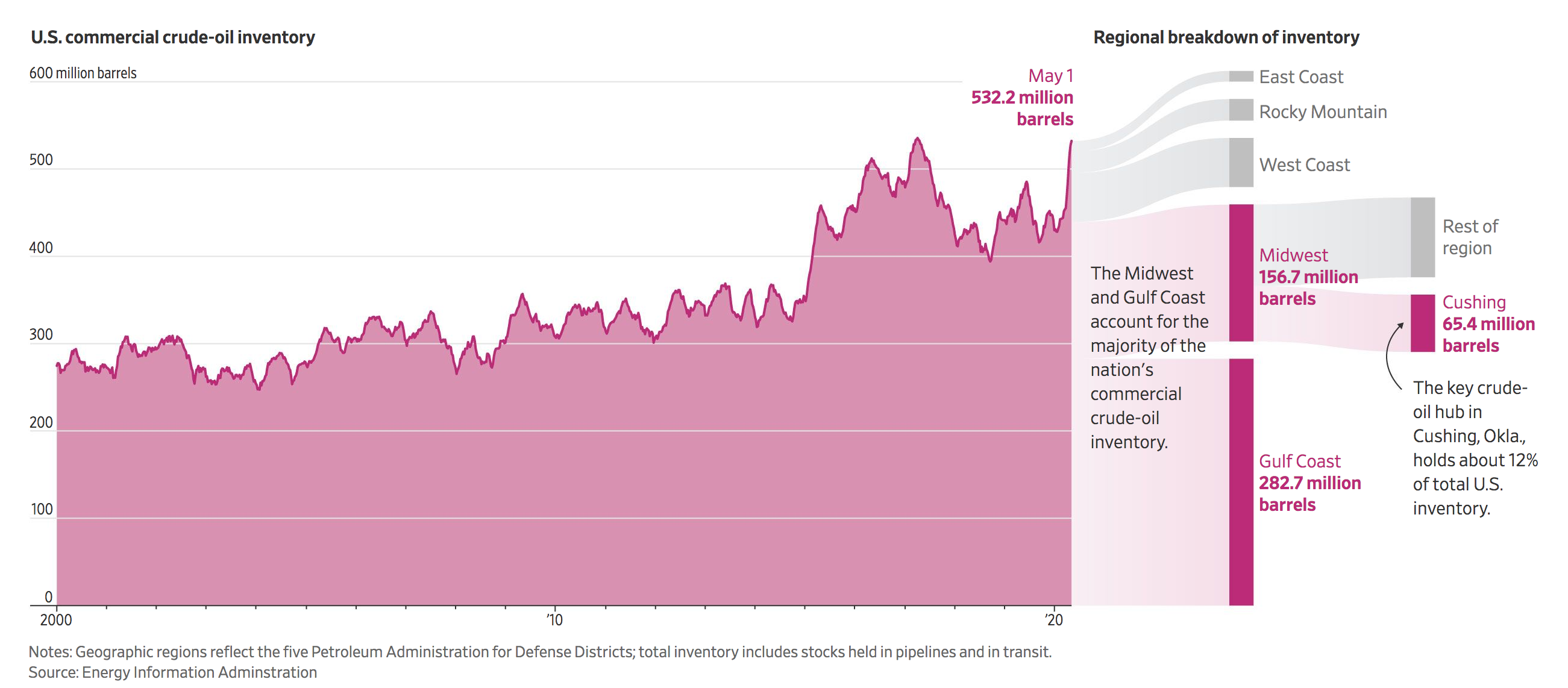

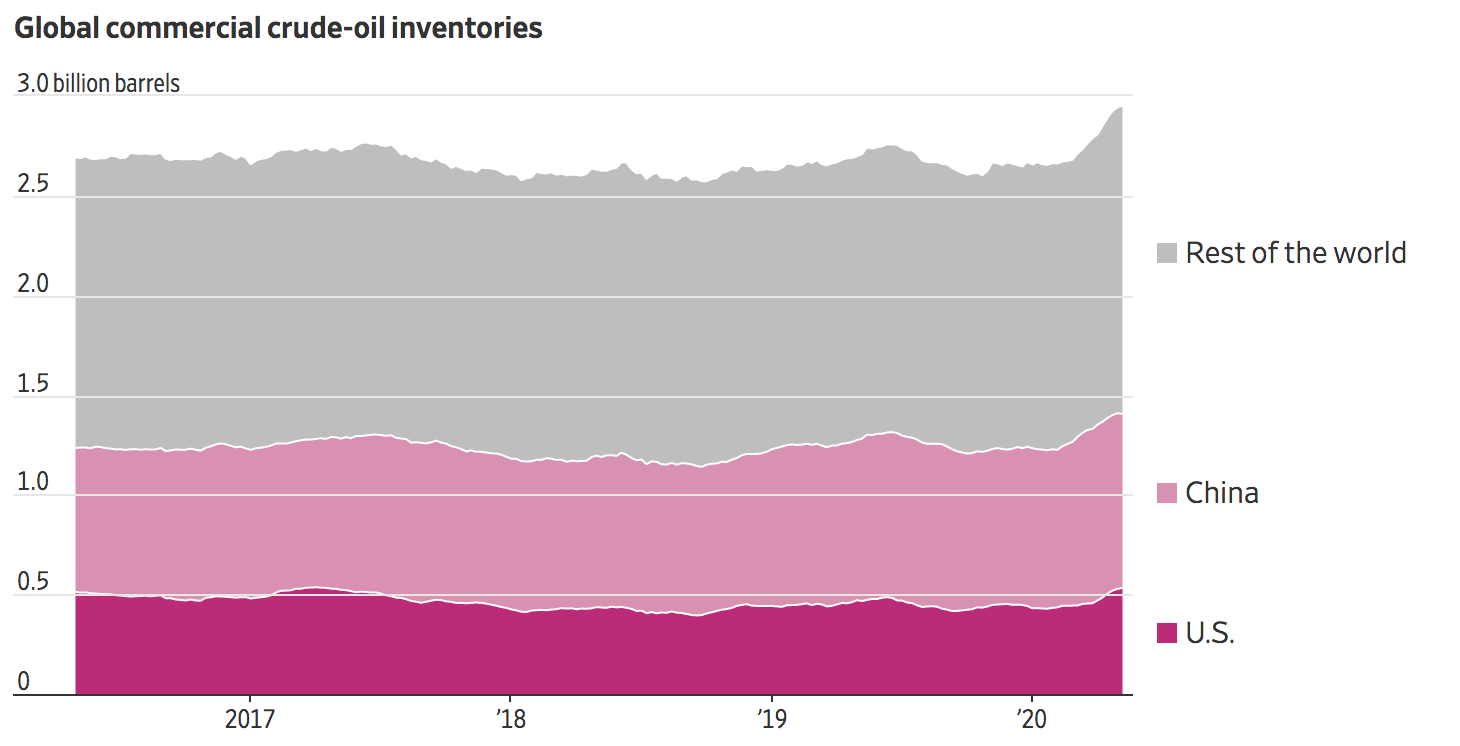

Daily consumption of petroleum products in the U.S. fell 19% during the week ended April 3 to what is at least a 30-year low, the EIA said. Domestic crude inventories swelled by the biggest weekly increase on record.

At that rate, the world would run out of places to put oil within about 60 days, analysts with Houston’s Simmons Energy estimate. Some analysts think the world’s storage caverns, tank farms, pipelines, refineries and ships will fill even faster.

Alberta’s energy minister, Sonya Savage, said Sunday’s pact by major producers could slow the march to an eventual topping out of storage tanks, which are close to full in Canada. “It’s getting close,” she said, adding that the status quo that existed before these talks was “unsustainable.”

Canada has room for fewer than four days’ worth of production, energy data provider Genscape Inc. estimates. In the U.S., there is much more storage capacity, but it isn’t evenly available to producers.

A refiner teeming with, say, jet fuel, may not be able to take in more crude from its suppliers even if there is demand for other products, like diesel. Backed-up pipelines could strand barrels.

“We‘ve been told by two of my markets they won’t take my production in May because there’s nowhere to put it,” said Russell Gordy, a Texas oilman with wells in his home state, Colorado, Wyoming and the Gulf of Mexico. “We won’t have to shut in everything, but we’ll have to shut in most of our production.”

Larger companies are shutting in wells too. Continental Resources Inc., which drills in Oklahoma and North Dakota, said it would reduce output in April and May by about 30%.

In West Texas, Parsley Energy Inc. has shut in about 150 older wells that together produced about 400 barrels a day, and were no longer worth the expense of powering the equipment inside, daily maintenance and paying out royalties, said Chief Executive Matt Gallagher.

Output from newer shale wells can be reduced without shutting them in entirely. But those big wells, with horizontal bores that stretch for miles, usually produce oil at the lowest costs, which makes choking them back unappetizing to producers scratching for every penny.

Canadian producers have eliminated roughly 325,000 barrels of daily output, according to consulting firm Rystad Energy, which predicts ultimate declines of about 1 million barrels, or nearly 25%. Suncor Energy Inc. has shut down one of two production lines at its 200,000-barrel-a-day Fort Hills oil sands mine in northern Alberta. Others have capped smaller wells.

“We have small companies that have shut every drop in,” said Kent McDougall, chief commercial officer at Alberta oil trucker Torq Energy Logistics.

Producers are doing so without knowing what will happen when they try to resume production.

Canadian crude is often called bitumen, which is as thick as peanut butter unless it is heated. Producers shovel up reserves close to the surface, but deeper deposits are coaxed out by injecting steam underground. Shutting down such operations is risky and expensive. Restarting them is touchy. It can take a long time to warm up the wells to resume flow, and there’s no guarantee they will be as productive.

In the U.S., the risks usually have to do with water. It can flood reservoirs, alter pressure and, since deep groundwater is salty, corrode components downhole.

That is what worries Texland’s Mr. Wilkes. The company has no experience restarting its wells and he can only guess what problems might arise once the artificial lift systems in its wells are powered down.

“Some wells may take time to recover to their previous production rate,” he said. “Some may never recover.”

Updated: 4-14-2020

Thirst For Oil Vanishes, Leaving Industry In Chaos

As people stay home to avoid the new coronavirus, the petroleum business is ‘experiencing a shock like no other in its history’.

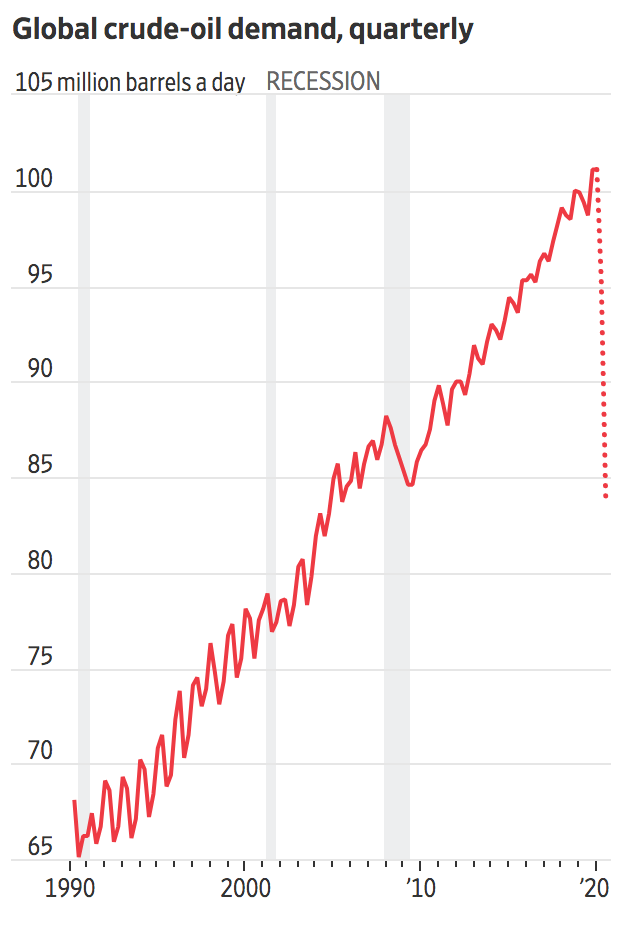

No one expected 2020 would unleash a world-wide oil-production cut led by the U.S., Saudi Arabia and Russia. But since the new coronavirus hit, the world’s thirst for oil has vanished, creating an unprecedented crisis for one of the planet’s most powerful industries.

With billions of people in lockdown to avoid the virus, crude-oil demand has collapsed as people stop driving and airplanes are grounded.

There is too much gasoline and jet fuel on the market, so refineries that turn crude into fuel are slowing oil purchases. Oil-storage facilities from Asia to Africa and the American Southwest are filling up. Producers have begun to shut in wells whose oil has nowhere to go.

The result is a breakdown of parts of the supply chain that delivers one of the world’s most important commodities. “The global oil industry is experiencing a shock like no other in its history,” said Fatih Birol, executive director of the International Energy Agency.

Over the weekend, a coalition of nearly two dozen of the world’s largest oil-producing countries agreed to withhold 9.7 million barrels a day from markets. It is unclear if this level of coordinated cuts is enough to erase the glut. Mohammed Barkindo, secretary-general of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, has described the fundamentals in the oil market as “horrifying.”

Global demand for crude is normally around 100 million barrels a day. Estimates of the decline vary widely and change daily, but most put current demand at 65 million to 80 million barrels a day. In volume and percentage, the fall exceeds the collapse of 1979 to 1983. It occurred over four weeks, not four years.

‘This Is Uncharted’

“Since humans started using oil, we have never seen anything like this,” said Saad Rahim, chief economist at Trafigura Group Pte. Ltd., a Singapore commodity-trading company that estimates demand at 65 million to 70 million barrels a day. “There is no guide we are following. This is uncharted.”

Not Thirsty

Crude-oil demand has fallen in an unprecedented manner, sending the global oil industry into a tailspin.

For weeks, the industry has been producing more than $500 million a day of crude no one wants to buy. The U.S. benchmark oil price, West Texas Intermediate, fell to just above $20, an 18-year low, at the end of March. It closed Monday at $22.41, down 63% from the year’s start.

Prices in some other hubs are substantially lower. In western Canada, oil closed Monday at $3.16 a barrel, down 84% from a month earlier.

“If you buy a cargo today, as a trader, you are not sure you will ever find a buyer for it because everyone has too much oil,” said Torbjörn Törnqvist, chief executive of Gunvor Group Ltd., which trades energy products in more than 100 countries. He worries that, in a couple of weeks, global energy markets will become “dysfunctional.”

Behind it all is the decision by governments to order or urge citizens to stay home. Normally, about 60% of the world’s oil goes toward making transportation fuels. Now, traffic counters and satellite images show a world immobilized.

Outside Milan, the normally jostling crowds at the Carosello mall were replaced by a smattering of shoppers, according to Paris-based satellite-data company Kayrros. In late March, vehicle crossings at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge fell 71% from a year earlier, a bridge spokeswoman said. The global aviation industry’s number of seats for sale as of April 13 was a third that in January, according to OAG, an aviation industry data firm.

Oil producers have been slow to react. It can be difficult and expensive to turn off an oil field and turn it back on. No one wants to be first to cut, and cede market share, so a global game of chicken is playing out.

Thin Air

Airline operations have contracted significantly since January 20th, as measured in passenger seats.

In South Africa, the giant Saldanha Bay oil-storage terminal is full, said Trafigura’s Mr. Rahim. The government agency operating the tank farm didn’t respond to inquiries.

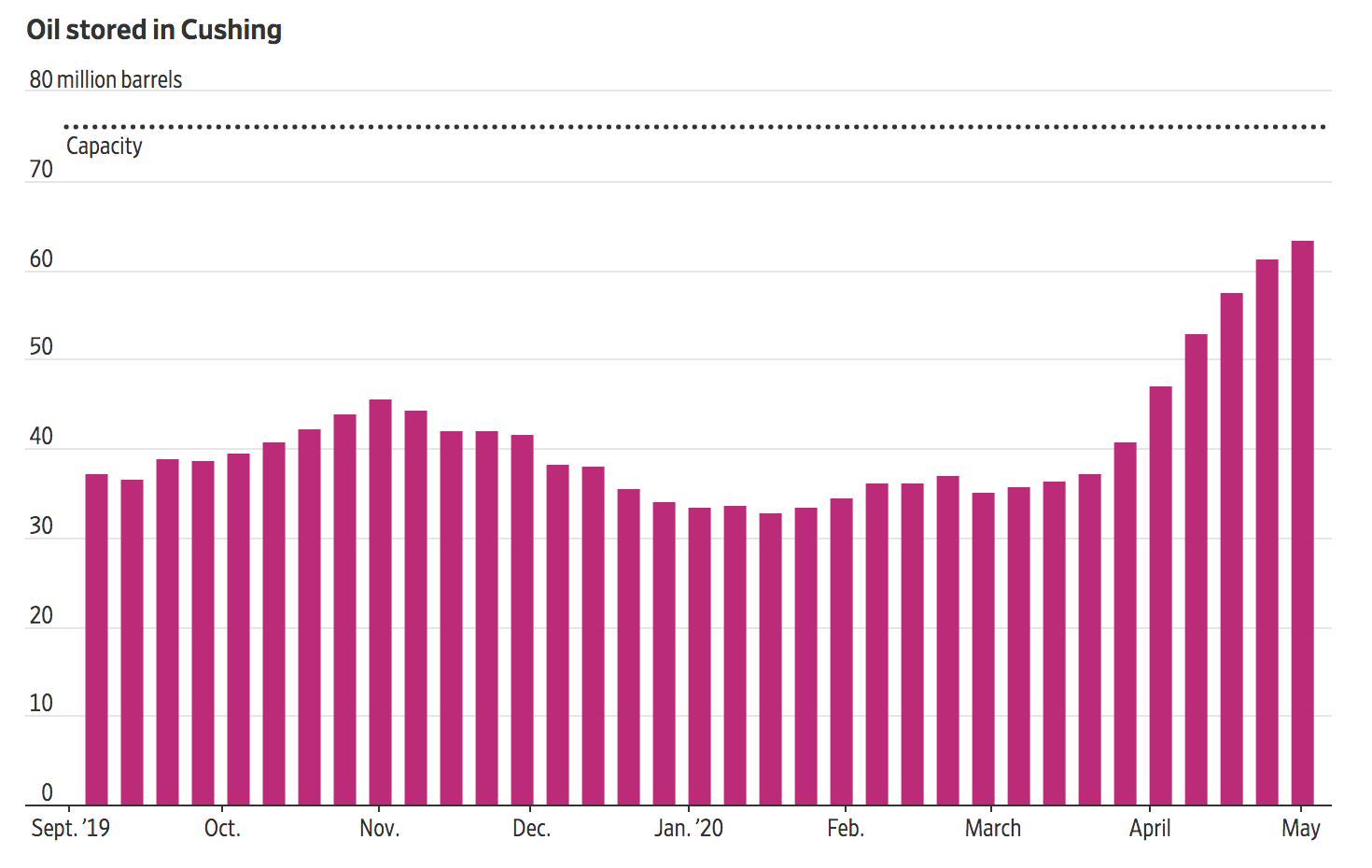

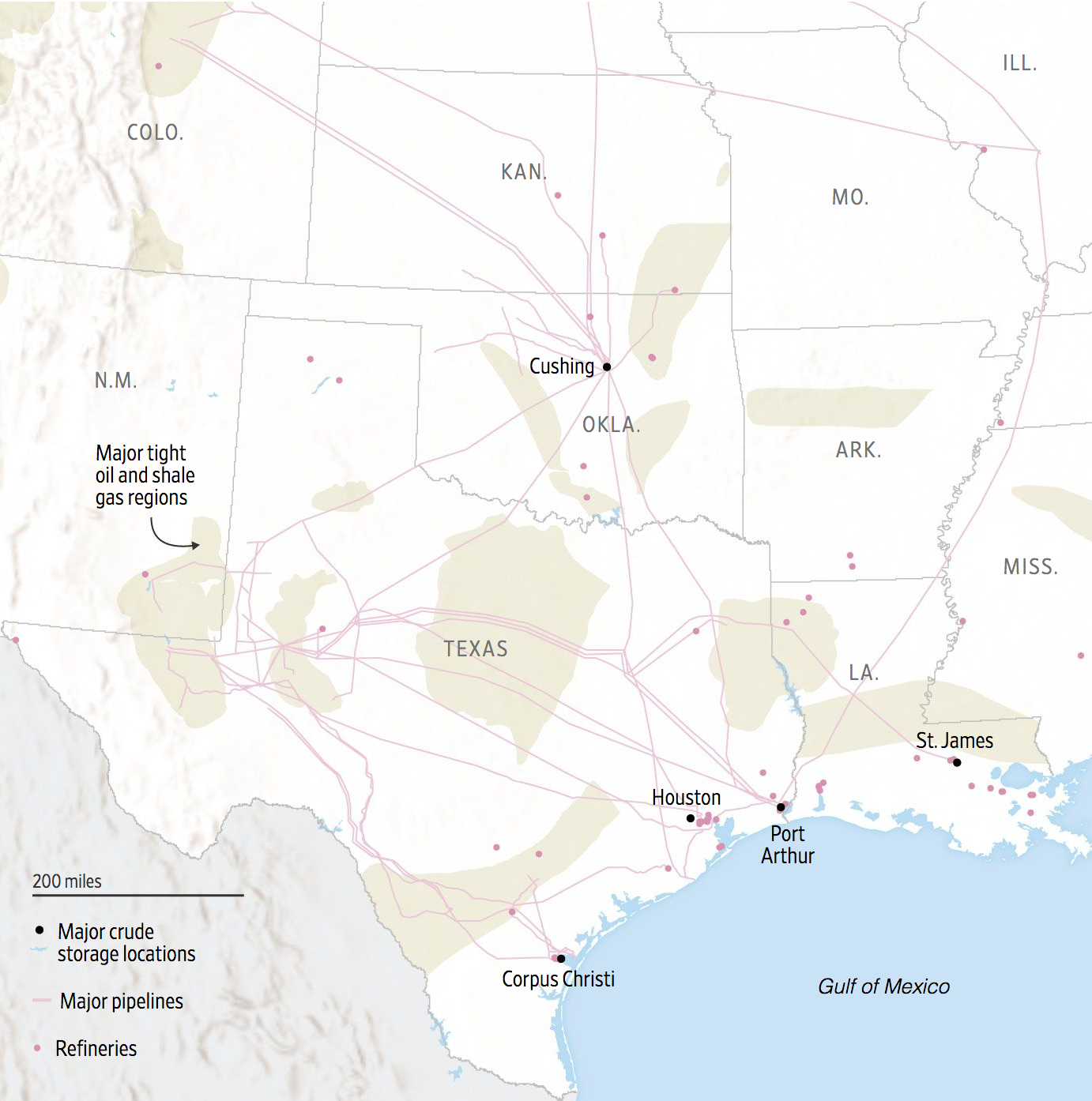

Earlier this year, Kevin Foxx’s four cylindrical tanks capable of holding a total 700,000 barrels of crude in the Cushing, Okla., area—the main pipeline-and-trading hub in North America—were less than half full. Now, the chief executive of Barcas Pipeline Ventures LLC said he expects them to be filled by this month’s end.

When Cushing fills, pipelines from the Permian Basin and Gulf Coast will have to order shippers to stop adding crude.

The system, Mr. Foxx said, will reach its limit. “Nothing is available,” he said. “If there’s nowhere to go in Cushing, if the pipelines are full, now we’re backed up to the producer.”

Colonial Pipeline Co., whose 5,500-mile conduit carries gasoline from Gulf Coast refineries into the Washington, D.C., and New York metro areas, issued a stern reminder in mid-March: Shippers couldn’t put gasoline into the nation’s largest fuel-conveyance system if they didn’t have contracted buyers. Operators like Colonial don’t want their pipelines to become parking lots for fuel.

While the pandemic has battered many industries, repercussions are likely to be long-lasting for global oil. Demand had plummeted during an existing oversupply, exacerbated by a price war between Russia and Saudi Arabia that broke out as the coronavirus was taking hold. Last month, Saudi Arabia increased production, saying it would raise output more than 2.5 million barrels a day to 12.3 million, before reversing course earlier this month.

Great Depression

The only time the combination of falling demand and a supply increase was even close to the current situation was in the 1930s with the discovery of the giant East Texas oil fields during the Great Depression. Crude fell to 24 cents a barrel in August 1931, a little more than $4 adjusted for inflation; demand declined gradually over several years.

In response, the Railroad Commission of Texas started regulating output, beginning decades of government interventions in global oil markets. Texas hasn’t curtailed oil production for more than a half-century, but the state agency served as the model for OPEC. Texas regulators say they are debating whether to cut state output again.

Optimists such as energy economist Philip Verleger believe the industry will be able to regain its footing once virus-related lockdowns are lifted and people begin to move again.

“The current downturn is harsh, but probably not the worst ever, especially if the global economy rebounds as many expect,” he said. Still, he believes one has to go back to the 1930s to find anything comparable. “We haven’t seen a demand shock like this in 90 years,” he said, adding that the 2020 contraction has been much quicker than during the Great Depression.

Prices remain below what most companies need to operate existing wells without losing money. In a recent Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas survey, oil operators estimated it cost them $26 to $32 to produce a barrel from an existing well in the Permian Basin of West Texas and southeastern New Mexico.

At $20, operators across the basin would lose a combined $200 million a week, an analysis of data that producers reported to the Dallas Fed suggests.

Whiting Petroleum Corp. filed for bankruptcy protection this month, the first major producer to fall this crisis. Energy analytics firm Rystad Energy said that at $30 oil, more than 70 U.S. oil-and-gas producers could have trouble making interest payments on their debt this year; at $20 crude, it would increase to about 140 companies.

“It’s a Grand Canyon of a supply-demand void,” said Matt Gallagher, chief executive of Parsley Energy Inc., a major Permian oil producer. Parsley, along with many other Permian producers, is shutting down uneconomic wells and has cut its planned capital expenditures this year to conserve cash. Mr. Gallagher is urging the U.S. government to impose a two-to-three-month embargo on importing some overseas crude, which would effectively reverse several decades of U.S. policy encouraging the free flow of global oil.

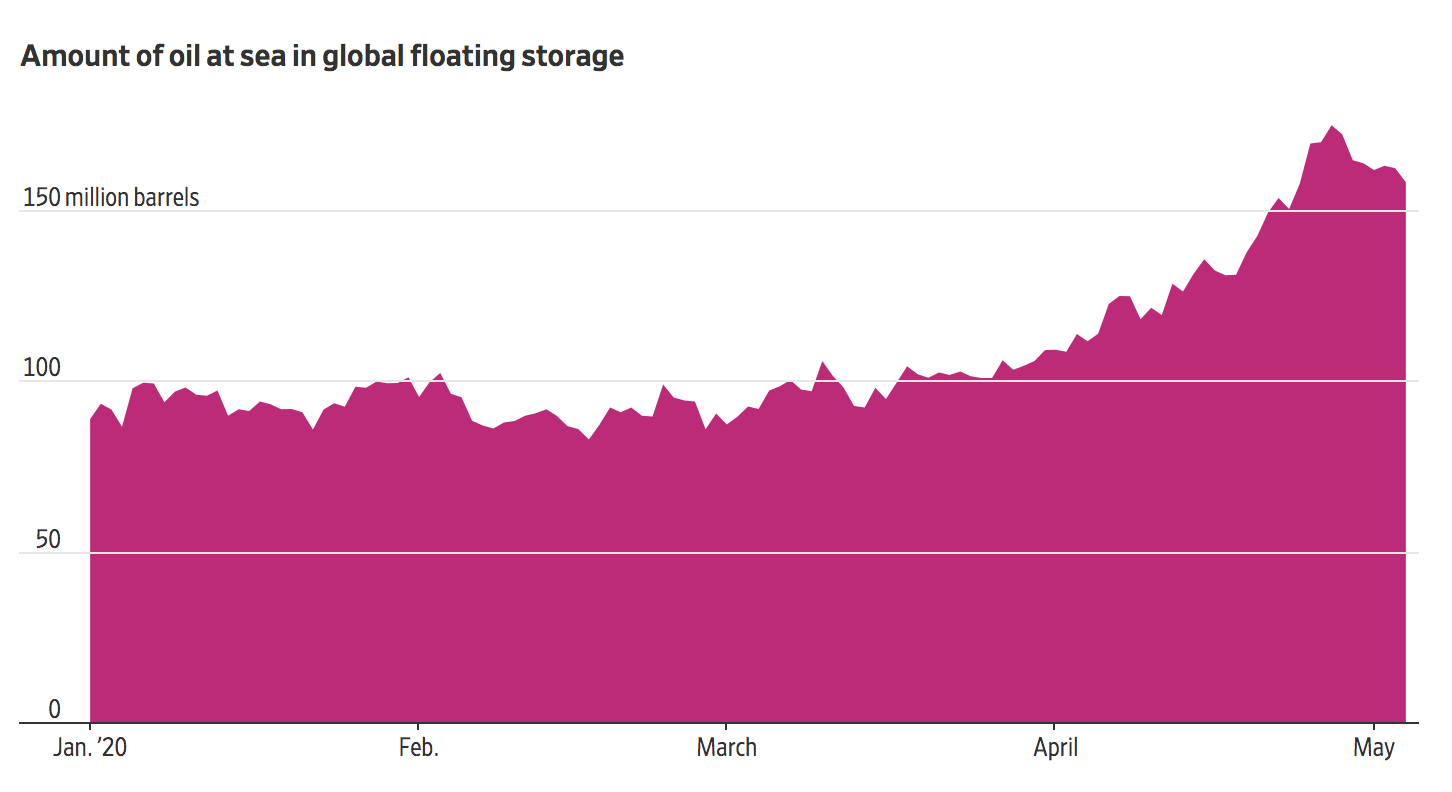

Mr. Gallagher has reason to worry: As part of its battle to capture market share, Saudi Arabia has a flotilla of cut-rate crude en route to the U.S. and Europe. The world’s largest oil exporter, it went on an early-March ship-hiring spree in Singapore, where many giant tankers called Very Large Crude Carriers, or VLCCs, were unchartered amid collapsing demand.

Within days, it had leased 24 supertankers, said Anoop Singh, head of tanker research in Asia at Braemar ACM Shipbroking Ltd. “They wanted it first,” he said, “they wanted it quick.”

Several VLCCs are now sailing toward Houston and could further inundate the U.S. market.

Storage Is Power

In a world of excess supply, controlling storage is power, and Saudi Arabia has become king of it. Oil stored inside the country rose by 8 million barrels to 79 million in 2½ weeks before March 26, according to satellite firm Kayrros.

The Saudis booked remaining capacity in an Egyptian storage facility, according to Saudi officials and traders. Still, demand fell faster than it could lease storage. In late March, as India entered lockdown, Indian Oil Corp., the country’s largest oil refiner, cut its output one-third. A Saudi energy-ministry spokesman didn’t return requests for comment.

If Saudi Arabia isn’t able or willing to return to its role as the globe’s central bank of oil—cutting output when the market is oversupplied, adding when undersupplied—then an untethered and volatile market will dictate prices.

“We are just going to have to buckle up,” said Bob McNally, a former energy adviser to President George W. Bush and author of “Crude Volatility,” a study of oil’s boom-and-bust cycles, “and learn to run the world with Space Mountain oil price cycles.”

Updated: 4-15-2020

Glutted Oil Markets’ Next Worry: Subzero Prices

Traders of physical barrels of crude brace for the possibility of negative pricing; traders of energy derivatives also wary.

The coronavirus pandemic is turning oil markets upside down.

While U.S. crude futures have shed half of their value this year, prices for actual barrels of oil in some places have fallen even further. Storage around the globe is rapidly filling and, in areas where crude is hard to transport, producers could soon be forced to pay consumers to take it off their hands—effectively pushing prices below zero.

The collapse is upending the energy industry and even the math used in trading energy derivatives. CME Group, the world’s largest exchange by market capitalization for trading futures and options, now says it is reprogramming its software in order to process negative prices for energy-related financial instruments.

Part of the problem, traders say, is the industry’s limited capacity to store excess oil. Efforts to curb the spread of the virus have driven demand to record lows. Factories have shut. Cars and airplanes are sitting immobile. So refineries are slashing activity while stores of crude rapidly accumulate.

U.S. crude inventories surged by a record 15.2 million barrels during the week ended April 3, according to data from the Energy Information Administration. Gasoline stockpiles also jumped, climbing by 10.5 million barrels, while refining activity hit its lowest level since September 2008.

The buildup of crude is overwhelming storage space and clogging pipelines. And in areas where tanker-ship storage isn’t readily available, producers could need to go to extremes to get rid of the excess, said Jeffrey Currie, head of commodities research at Goldman Sachs. Those might include paying for it to be taken away.

“It’s like traffic on a freeway,” he said. “It gets congested when there are a lot of cars.”

Crude comes in many varieties, used for a range of purposes, and different grades are priced based on several factors, including their density, sulfur content and ease of transportation to trading hubs and refineries. Heavier, higher-sulfur crudes generally trade at a discount to lighter, sweet crudes such as West Texas Intermediate because they tend to require more processing. Crudes that depend on pipeline transportation are trading at a discount right now because there is nowhere to put them and the pipelines that would normally take them away are getting jammed up, analysts and traders say.

The price of some regional crudes recently dipped into single digits. The spot price of Western Canadian Select at Hardisty—a heavy grade of Canadian crude typically transported by pipeline or rail to the U.S. Gulf and Midwest for refining—fell to just over $8 a barrel on April 1, according to an assessment from S&P Global Platts.

The spot price of West Texas Intermediate at Midland fell to just above $10 a barrel on March 30, while West Texas Sour at Midland—its harder-to-refine counterpart—fell to around $7 a barrel. And one commodities trading house recently bid less than zero dollars for Wyoming Asphalt Sour crude.

It isn’t just the traders of so-called physical oil who are bracing themselves for the possibility of negative pricing. Traders of energy derivatives are preparing, too. Mark Benigno, co-director of energy trading at INTL FCStone, said he has never seen oil derivatives trade below zero but began several weeks ago to assess what might happen if they do.

“It’s something we have to consider,” he said. “Options are structured to go to zero. That puts a limit on how much you can lose. When they go below that, it becomes a different situation entirely.”

In recent weeks, traders have pinned hopes for a rebound on the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and other oil-producing nations.

Over the weekend, Saudi Arabia and Russia ended a production feud and joined the U.S. to lead a coalition of 23 oil-producing countries to cut output by a collective 9.7 million barrels a day. The feud began in March after Russia refused to participate in a Saudi-backed plan to carry out coordinated cuts. Saudi Arabia then lowered prices and raised production of its barrels, sending global prices into a downward spiral.

However, traders and analysts say the demand lost due to the coronavirus far exceeds the supply cuts.

“It’s not nearly enough to make a significant shift in balancing the market,” said Chris Midgley, global head of S&P Global Platts Analytics.

U.S. benchmark prices tumbled 10% on Tuesday and are down 67% so far this year.

Prices could get a boost as energy producers are forced to shut off the taps, analysts and traders say. The fall in oil prices has hit producers hard. Chevron Corp., Exxon Mobil Corp. and Diamondback Energy Inc. have pledged to slash spending. U.S. shale driller Continental Resources Inc. recently said it would cut its output by around 30% in April and May and suspend its quarterly dividend. Denver-based Whiting Petroleum Corp. filed for bankruptcy.

Some analysts see a glimmer of hope coming from China, where there are some signals of life returning to normal. Chinese consumers have cautiously begun to travel again after hunkering down at home for two months.

Others aren’t as optimistic, noting that global oil demand is still falling by tens-of-millions of barrels a day.

“We really don’t know when demand will come back online,” said Rusty Braziel, chief executive of RBN Energy.

Updated: 4-20-2020

U.S. Oil Costs Less Than Zero After A Sharp Monday Selloff

Many traders are betting that the coronavirus pandemic will run its course and demand for oil will jump later this year.

U.S. oil futures plunged below zero for the first time Monday, a chaotic demonstration that there was no place left to store all the crude that the world’s stalled economy would otherwise be using.

The price of a barrel of West Texas Intermediate crude to be delivered in May, which closed at $18.27 a barrel on Friday, ended Monday at negative $37.63. That effectively means that sellers must pay buyers to take barrels off their hands.

The historic low price reflects uncertainty about what buyers would even do with a barrel of crude in the near term. Refineries, storage facilities, pipelines and even ocean tankers have filled up rapidly since billions of people around the world began sheltering in place to slow the spread of the deadly coronavirus.

Prices remain in positive territory for barrels to be delivered in June. In the most actively traded U.S. futures contract, crude for June delivery closed Monday at about $21, while oil due to be delivered to the main U.S. trading hub in Oklahoma in November ended at around $32.

Even before May’s price went negative, the spreads between oil now and later were records, reflecting the sharp decline in transportation-fuel demand as well as a wager that people will return to driving cars, flying on airplanes and working at factories in the months to come.

Monday’s chaotic trading was exacerbated by the looming expiration of the May futures contract on Tuesday. The price of oil futures converge with the price of actual barrels of oil as the delivery date of the contracts approach.

Though producers from Alberta, Canada to Midland, Texas are racing to shut in productive wells, they haven’t been able to close off the spigot fast enough to avoid what energy executives have been referring to as “hitting tank tops” and running out of places to store crude and petroleum products, such as gasoline and jet fuel.

The producers’ pain presents a rare opportunity for traders, who are filling up tankers with crude and setting them adrift. Their bet is that the coronavirus pandemic runs its course and later this year demand for oil—and thus its price—will jump.

“If you can find storage, you can make good money,” said Reid I’Anson, economist for market-data firm Kpler Inc.

Increasingly, traders are looking offshore. Lease rates have soared for very large crude carriers, the 2-million-barrel high-seas behemoths known as VLCCs.

The average day rate for a VLCC on a six-month contract is about $100,000, up from $29,000 a year ago, according to Jefferies analyst Randy Giveans. Yearlong contracts are about $72,500 a day, compared with $30,500 a year ago. Spot charter rates have risen sixfold, to nearly $150,000 a day.

Day rates rise as the spread between oil-futures contracts widens. The basic math is that every dollar in the six-month spread equates to an additional $10,000 a day that can be paid for a VLCC over that time without wiping out all the oil-price gains, Mr. Giveans said.

May delivery futures of Brent crude, the international benchmark typically used to price waterborne oil, ended Friday at $28.08 a barrel. The contract for November delivery settled at $37.17. The $9.09 difference wouldn’t justify a $100,000 day rate, but the record spread of $13.45 reached on March 31 does.

At the end of March there were about 109 million barrels of oil stowed at sea, according to Kpler. By Friday it was up to 141 million barrels.

The collapse in current oil prices, combined with the expectations that a lot of economic activity will resume by autumn, has resulted in a market condition called contango—in which prices for a commodity are higher in the future than they are in the present.

One of the great trades in modern history involved steep contango and a lot of oil tankers. In 1990, Phibro, the oil-trading arm of Salomon Brothers, loaded tankers with cheap crude just before Iraq invaded neighboring Kuwait and crude prices surged. The trade’s architect, Andy Hall, rose to fame, bought a century-old castle in Germany and became known for a $100 million payday.

Present market conditions have inspired emulators.

In the past four weeks, nearly 50 long-term contracts have been signed for VLCCs, Mr. Giveans said. Jefferies has identified more than 30 of them as being intended for storage, usually because they are leased without discharge locations. The coast of South Africa offers popular anchorage since it is relatively equidistant to markets in Asia, Europe and the Americas.

“We’ve seen more floating-storage contracts signed for 12 months in last three weeks than we’ve seen in the last three years,” Mr. Giveans said.

Companies that own and operate pipelines and oil-storage facilities could gain as well.

Consider the difference between Friday’s price for West Texas Intermediate to be delivered in May, which was $18.27 a barrel, and in May 2021, which closed at $35.52: A $17.25 spread could be locked in by buying contracts for oil to be delivered next month and then selling contracts for delivery a year later.

Assuming monthly costs for storage owners of 10 cents a barrel—as Bernstein Research analysts did when they ran back-of-the-envelope storage math in a recent note to clients—leaves a profit of $16.05 a barrel.

Companies don’t usually disclose unused storage capacity, but it is possible that bigger players such as Energy Transfer LP, Enterprise Products Partners LP and Plains All American Pipeline LP could have room for tens of millions of barrels, the Bernstein analysts said.

Updated: 4-21-2020

Oil-Price Crash Deepens, Weighs on Global Markets

Stocks fall as U.S. crude benchmark plunges, a day after one contract fell below zero.

A fresh plunge in oil prices dragged down investments from stocks to currencies Tuesday, stinging investors anew and adding even more urgency to the crisis sweeping the energy industry.

Major U.S. stock indexes have largely shrugged off concerns about bankruptcies and job losses in the energy sector while rebounding from a March 23 multiyear low. But this week’s drops show that recent chaos in the world’s busiest commodity market is beginning to compound lingering worries about the coronavirus.

The most heavily traded U.S. crude-oil futures contract fell 43% Tuesday to $11.57 a barrel, its lowest close in 21 years. Its record low is $10.42 in data going back to 1983. Tuesday’s drop came a day after one contract for U.S. crude fell below zero for the first time in history, forcing sellers to pay buyers to take barrels off their hands.

Anxiety about the crash’s impact on large energy producers from the U.S. to Saudi Arabia helped drag the S&P 500 down 3.1%, bringing the broad equity gauge’s fall for the week to nearly 5%. It is still up more than 20% from its March low, but traders say the energy sector’s struggles could contribute to further falls.

Energy analysts say the scope of the oil demand lost to the coronavirus means there is little producers can do to give prices a short-term boost. President Trumpin a tweet Tuesday said he had directed the Energy and Treasury departments to craft a plan to make funds available for the oil-and-gas industry. “We will never let the great U.S. Oil & Gas Industry down,” he wrote.

The Trump administration is considering offering federal stimulus funds to embattled oil-and-gas companies in exchange for government ownership stakes in the companies or their crude reserves, The Wall Street Journal reported.

Still, government data due Wednesday are expected to show another big increase in oil stockpiles for last week. Texas regulators declined to act Tuesday on a proposal to limit state oil supply, but some shale producers are already being forced to shut in productive wells. The expected supply drops are dwarfed by lost demand.

“Demand is contracting two or three times as fast as supply,” said Bob McNally, president of consulting firm Rapidan Energy. The drop in prices is a “brutal but efficient” mechanism to “persuade producers to keep oil under the crust,” Mr. McNally said.

“The looming question is now how some of these big energy companies are going to stay afloat,” said Mohit Bajaj, director of exchange-traded fund trading solutions at WallachBeth Capital. “People are pointing fingers in the market to the move in oil… It’s a big shift.”

Investors sold everything from energy stocks to currencies of major suppliers like Russia on Tuesday. Analysts expect a big drop in energy-industry spending to amplify the economic fallout from the coronavirus, with factories shut, streets empty and consumers unable to take advantage of low fuel prices.

Energy producers have lost hundreds of billions of dollars in market value this year, and shares fell again Tuesday. Royal Dutch Shell PLC and BP PLC lost at least 3%, as did some U.S. companies. Speculation about bankruptcies and possible mergers in the industry is driving wild stock-price swings, and possible issues with energy loans could ripple to the banking industry.

Producers are unable to shut wells fast enough, and supply cuts by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and other nations have come too late. Traders say that the world is running out of space to store oil, driving prices below $0 a barrel for the first time on Monday.

“Traders just capitulated to the fact of the limited access to storage,” said Eelco Hoekstra, chief executive of Royal Vopak NV, a Dutch firm that runs 66 terminals for storing commodities around the world. “It’s been brutal.”

Vopak has already rented out almost all of its oil terminals, Mr. Hoekstra added.

Brent crude futures, the international benchmark for oil markets, dropped 24% to $19.33 a barrel, their lowest level in more than 18 years. The U.S. contract for delivery next month, which settled at a historic minus $37.63 a barrel Monday, rose to expire at $10.01 in thin trading Tuesday.

“Whatever oil analysts and oil traders have learned over the course of the last 50 years or 100 years was all of a sudden put in question” by Monday’s negative oil prices, said Eugen Weinberg, head of commodities research at Commerzbank. “Everyone has been shocked.”

The plunge has burned individual investors who had poured money into United States Oil Fund LP as they bet on a revival in oil prices in recent weeks. The popular exchange-traded fund fell 25% Tuesday, taking its rout this year to nearly 80%. The company that operates the ETF is reshaping it for now into what will effectively be a closed-end fund with a fixed number of shares and fewer near-dated crude futures contracts.

Oil futures, used by investors to bet on the direction of prices and by producers to protect against market swings, had performed better than the physical oil market for several weeks. Now, they are being stung by the slide in demand for actual barrels of crude.

“This is the market signaling to producers that you need to cut off more production faster because we’re drowning in oil at this point,” said Saad Rahim, chief economist at Swiss commodities trader Trafigura.

Market mechanisms that might help address the slump appear to be breaking down because of the lack of storage space.

Typically, low U.S. prices would encourage traders to buy cheap American oil and sell it at a higher price in Europe or Asia. The way Brent crude prices sank in tandem with WTI on Tuesday suggests “the world doesn’t want to take U.S. barrels,” said Vincent Elbhar, co-founder of Swiss hedge fund GZC Investment Management.

Recent moves also prompted discussions between Saudi Arabia and other members of OPEC about whether to cut production immediately. OPEC members are considering bringing forward the start date for production cuts from May 1.

“We have to face up to the reality that despite OPEC’s pledge, a lot of May cargoes have already been committed,” said Harry Tchilinguirian, head of commodities research at BNP Paribas. In effect, he said, “the cuts will only start to happen in June.”

U.S. oil companies including Chevron Corp. and ConocoPhillips have said they would reduce output. But traders say the industry isn’t moving fast enough to alleviate the selloff. This week’s price moves will be a huge wake-up call for complacent oil-company chiefs, said Edward Marshall, a commodities trader at Global Risk Management.

“If they do nothing and sit there like rabbits in the headlights waiting to be hit by a car, they’ll be hit,” he said. “I wouldn’t be surprised to see even more [capital expenditures] cuts…even more layoffs, even more jawboning by OPEC,” Mr. Marshall added. “It’s got serious now.”

Updated: 5-2-2020

Small Oil Drillers Are Turning Off Taps More Quickly Than Anticipated

From Texas and Wyoming to North Dakota, smaller companies are concluding it is better to keep oil in the ground after prices crashed.

Small U.S. oil companies are shutting off wells faster than expected, as prices fall below what it costs them to pump the crude out of the ground.

The collapse that sent U.S. benchmark prices into negative territory last week persuaded many smaller-scale, privately held drillers to shut many of their wells until the economy revs up again and demand bounces back. These drillers—in places like West Texas, New Mexico, North Dakota, Wyoming and Louisiana—collectively account for about a quarter of American production.

The pullback means that a sizable amount of U.S. oil production could stay in the ground for months, while refiners burn through a glut of crude in storage. Consequently, some observers have sharply revised U.S. forecasts for 2020 production, with faster and deeper cuts than previously expected.

Ken Waits, chief executive of Mewbourne Oil Co., one of the largest private producers in the Permian Basin of Texas in New Mexico, said many companies are receiving less for their crude than needed to cover operating costs. By next month, the Texas-based company expects to shut in more than half of the approximately 100,000 barrels a day it pumps in the region.

“What we’ve seen with the tremendous reduction in demand is just unprecedented,” Mr. Waits said. “Those prices are just not sustainable.”

Several small producers said they don’t plan on bringing wells back online until regional prices climb above $20 or $30 a barrel and stay there for a while. While U.S. prices have rebounded since April 20, they remained below $20 at $15.06 on Wednesday.

Iron Oil Operating LLC of Montana has stopped producing almost all of its 3,500 to 4,000 barrels a day in North Dakota’s Bakken Shale. In Louisiana, Velandera Energy Partners LLC said it has shut in about three-quarters of its oil output but declined to reveal the exact amount.

The motivation behind shutting in the wells is simple: Better to keep oil in the ground than lose money selling it at current prices. The bet is that prices will recover enough to cover restart costs and boost sales within a few months.

“I don’t want to see our production sold for a loss,” said Brent Allen, a managing director at Texas-based Alpar Energy LP. It has nonoperating interests in several West Texas wells that will be shut off over the next two months.

Private companies produced roughly a quarter of U.S. oil production last year, according to consulting firm RS Energy Group.

The shut-ins by smaller companies are a major reason U.S. oil production, which has recently led the world, is now projected to fall substantially in coming months.

Consulting firm Rystad Energy forecasts that U.S. output will fall from 12.8 million barrels a day in January to 10.9 million a day in June and as low as 10.3 million a day in September. In early April, before oil fell below $0 a barrel, the Energy Information Administration had predicted U.S. output would fall to 11.7 million barrels a day in June and about as low as 10.9 million a day in October.

The longer the shutdowns persist, the more likely that they lead to continued job reductions in the oil sector, executives said. When companies slash drilling-related spending, the oil-field services companies and contract workers that do much of the work are hit hardest.

Anschutz Exploration Corp. has shut in all of its wells in Wyoming’s Powder River Basin and let go of all the contract workers involved in their production. The Denver-based company had projected that the wells would produce the equivalent of 18,000 barrels of oil a day in April.

“We’re prepared to leave these wells shut in for an extended period,” said Joe DeDominic, the company’s president, noting it could take several months for prices to substantially recover.

While painful for companies and workers, the shut-ins could help rebalance the oil market. Production cuts of 9.7 million barrels a day by OPEC, Russia and other countries are set to begin taking effect in coming months.

“This is a slap in the face the market needed,” said Ben Luckock, co-head of oil trading at global commodities trader Trafigura Group Pte Ltd. “The market was producing too much crude oil.”

Mr. Luckock said U.S. production declines that Trafigura had originally forecast for the end of 2020 have been accelerated by six months and are now growing further.

Some larger U.S. shale drillers aren’t cutting production as steeply as their smaller peers. Pioneer Natural Resources Co. PXD -7.15% has shut down roughly 2,000 low-performing wells, nearly all of them older traditional oil wells. Their output totals only about 7,000 barrels of oil daily, or roughly 3% of the company’s daily output during the fourth quarter of last year, Chief Executive Scott Sheffield said. The company isn’t planning a wider shut-in program, he added.

“We’re 100% hedged, and we have firm transportation to the Gulf Coast. And we expect to export most of our crude,” Mr. Sheffield said.

Some smaller companies have higher production costs and don’t have the same ability to move their oil to customers. Trinidad Energy LLC plans to pump roughly 30 barrels a day, down from 225, and store oil at its field until prices rise enough to make it profitable again, said Kyle McGraw, the company’s president.

“My hope is we open the country back up and get people back to flying and driving,” Mr. McGraw said, adding that his storage tanks have enough capacity for about three months. “Is 90 days long enough?”

Updated: 5-6-2020

Oil’s ‘Relief Rally’ Stalls After Prices Double

The rally raises hopes—but not confidence—that the mounting fuel glut won’t overwhelm the world’s capacity to store oil.

Energy producers are throttling back their output, drivers are returning to the road and U.S. oil prices are roughly twice what they were a week ago, raising hopes—but not confidence—that the mounting fuel glut won’t overwhelm the world’s capacity to store oil.

Since reaching a record in mid-March, daily U.S. crude production has declined by more than a million barrels and big producers are promising to push it lower yet by shutting in old wells, waiting to bring online the newly drilled and dialing down flows where they can.

Meanwhile, demand for transportation fuels has begun to climb back from what was at least a 30-year low in early April. Executives at the largest U.S. refiner say that the worst of the historic drop in fuel demand caused by the coronavirus pandemic appears to be in the rearview mirror.

West Texas Intermediate for June delivery fell 2.3% to close at $23.99 a barrel Wednesday, its first decline after five days of gains. That is down 61% from the start of the year but a marked improvement from April, when supply and demand were so out of whack that it appeared there would be no place to store the excess and May futures contracts traded below $0 for the first time ever.

“I never thought $22 oil would be exciting,” said Diamondback Energy Inc.’s finance chief, Kaes Van’t Hof. That was early Tuesday, before the main U.S. oil price pushed higher to close at $24.56, up 99% from a week earlier. “It certainly looks better for the June month from a contract perspective than it did in May,” he said.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc. analysts call the climb a “relief rally” and said it would take much longer for West Texas Intermediate to double again. They don’t expect it to average more than $30 a barrel this quarter or next, but forecast U.S. oil to exceed $50 by the second half of 2021.

Given the glut motorists and airlines must burn through, producers will have to keep cutting production to buoy prices and prevent storage facilities from filling, they and other analysts say.

Companies such as Diamondback are doing their part. The Austin, Texas, firm, which produced about 200,000 barrels of oil a day during the first quarter, ceased bringing new wells to production in March and said it would reduce planned output by 15% this month.

“The risk of WTI prices declining further outweighs the benefit of producing as much as possible,” Chief Executive Travis Stice told investors on Tuesday.

Two of Diamondback’s rivals in the Permian Basin of West Texas said they would take even greater portions of their oil off the market.

Centennial Resources Development Inc. suspended drilling and well-completion work and plans to curtail up to 40% of its production this month. Parsley Energy Inc. has shut in hundreds of older wells that together produced more than 5,000 barrels a day and will choke back as much as 23,000 barrels a day in May. Pipeline operator Plains All American Pipeline LP said it expects roughly 1 million barrels of Permian production will be shut in this month.

“Currently the world does not need more of our product and we only get one chance to produce this precious resource for our stakeholders,” said Parsley CEO Matt Gallagher.

U.S. crude production was a record 13.1 million barrels a day in mid-March when many Americans were ordered to shelter in place to avoid spreading the deadly virus. By May 1, it was down to 11.9 million barrels as producers ranging from ConocoPhillips to scores of closely held concerns closed the spigots.

In the three weeks since April 10, when demand for transportation fuels was at multidecade lows, consumption of gasoline has risen 31% as parts of America began to reopen, according to U.S. Energy Information Administration data that approximately measure petroleum-product consumption. Jet fuel use, after rising 73% the week ended April 24, declined during the most recent week and is up 11% since April 10.

The U.S. Energy Information Administration is scheduled to release supply data for the week ended May 1 on Wednesday.

The data include approximate measures of petroleum-product consumption. Early last month, demand for gasoline and jet fuel plunged to multidecade lows.

In the two weeks since April 10, consumption of gasoline has risen 15% and jet fuel 73% as parts of America began to reopen.

There were an average of 76,833 daily flights during the week ended May 5, up 14% from April 10 though still not half as many as in February, according to flight tracker Flightradar24.