Foreign Buying of U.S. Treasurys Softens, Unsettling Financial Markets (#GotBitcoin)

Investor pullback has fueled a bond selloff and shaken a nine-year-long rally in stocks. Foreign Buying of U.S. Treasurys Softens, Unsettling Financial Markets (#GotBitcoin)

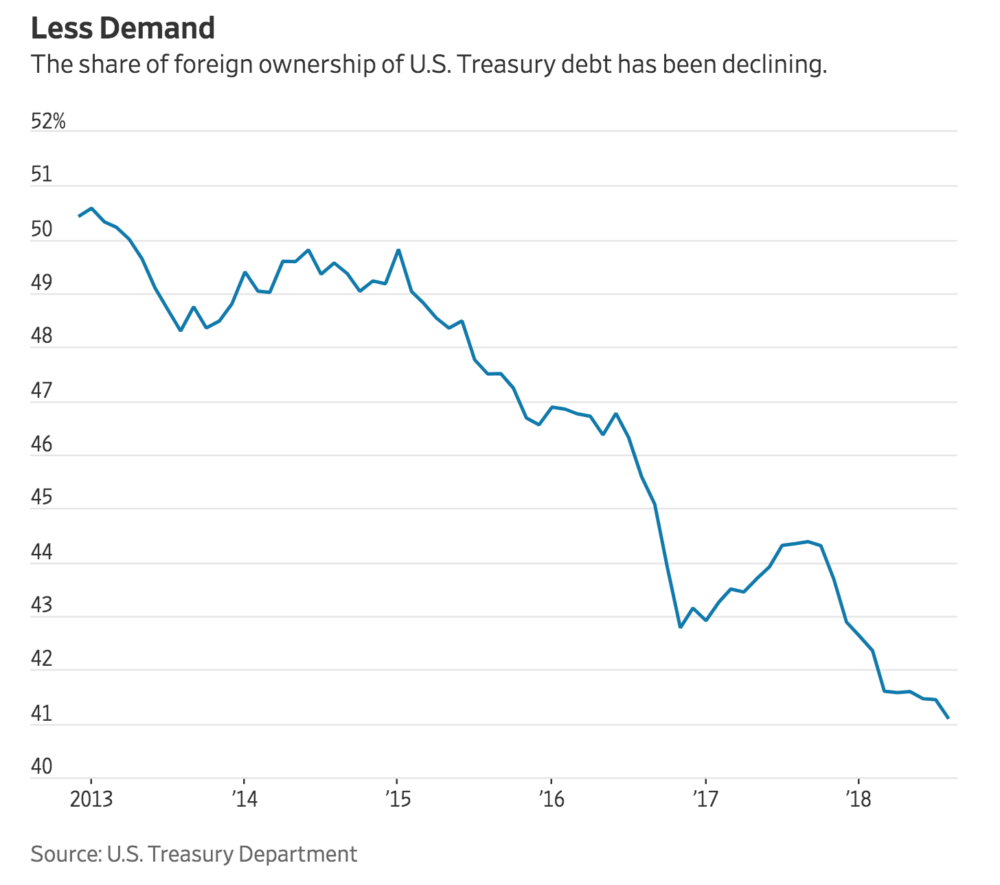

Foreigners increased their holdings of Treasurys by $78 billion in the first eight months of 2018. That is just over half of what they bought during the same period last year and accounts for a much smaller share of Treasury issuance, as the government steps up the size of regular bond auctions to fill a growing U.S. budget gap.

Foreign buyers now hold 41% of outstanding Treasury debt, their lowest share in 15 years, down from 50% as recently as 2013, according to U.S. Treasury data.

So far, U.S. yields remain low historically, debt funding remains broadly available and many foreign purchasers retain large stakes. China and Japan still both own more than $1 trillion of U.S. debt, according to the U.S. data, and there are few signs that Treasurys are losing their cachet as the world’s most widely traded, extensively held safe securities. Treasury yields serve as a reference rate for mortgages, business loans and other borrowing.

Yet it is clear that the foreign pullback has helped fuel a bond selloff this fall, which has driven the 10-year yield to 3.17% and has shaken the nine-year-long rally in U.S. stocks, and that continuing reductions in foreign appetite could further unsettle financial markets. Rising yields on Treasurys tend to hurt stocks by raising companies’ and investors’ borrowing costs and dimming the allure of dividend-paying stocks.

Bonds rallied Tuesday as worries about global growth and a downbeat outlook for U.S. corporate earnings dragged equities lower. The Dow Jones Industrial Average lost 0.5% and the 10-year yield, which falls as bond prices rise, retreated from its 2018 high of roughly 3.23% hit earlier this month. Yet the yield still held in its recent range above 3.1%.

“Yields are rising to reflect a risk premium, rather than healthy growth,“ said Mark McCormick, North American head of foreign exchange strategy at TD Securities. “People are concerned about how reliable a store of value the dollar is right now.”

Adding to the negative chatter about U.S. bonds: Some central banks, sovereign-wealth funds and global investors may be shedding dollars as they attempt to diversify their holdings, while others may have deemed their dollar reserves sufficient to weather the risk of economic turmoil.

The dollar’s share of global foreign-exchange reserves fell to 62.5% in the second quarter, its lowest level in five years, data from the International Monetary Fund showed. Goldman Sachs estimates that Russia’s central bank alone may have sold as much as $85 billion in dollar-denominated assets, a move that may have been prompted by concerns over U.S. sanctions.

One key factor keeping away foreign Treasury buyers is the high cost of reducing the currency risk of holding U.S. assets, a move known as hedging.

A U.S. 10-year note yields about 2.7 percentage points higher than German debt with a similar maturity, an unusually large margin. But investors in the currency market expect the euro to rise against the dollar as the European Central Bank begins raising interest rates next year, making the euro more attractive to yield-seekers.

By contrast, many believe the dollar’s value largely reflects monetary policy expectations in the U.S.: The Federal Reserve has raised rates eight times since 2015, and policy makers have penciled in four more increases by the end of 2019.

As a result, hedging dollars is expensive: Foreign investors must pay 3% on an annualized basis to hedge against fluctuations of the dollar, making the trade unprofitable for many.

Conventional wisdom suggests “as the Fed lifts rates it will pull money into the dollar—we’re the high yielder,” said Kathleen Gaffney, a bond manager at Eaton Vance. “Hedging costs are interfering with that now.”

The cost to hedge could widen further if investors come to expect the Fed could tighten policy more than expected or if the ECB scales back its forecasts.

Softening demand for Treasurys has also limited the dollar’s gains, analysts say, confounding those who expected the higher yields to make dollar assets more attractive to income-seeking investors. Though a stronger dollar is desirable for U.S. consumers because it enhances their purchasing power, it also raises investor fears about debt sustainability for emerging market countries that have borrowed heavily in the currency, such as Turkey, analysts said.

Jeremy Lawson, head of the Aberdeen Standard Investments Research Institute, which manages $730 billion, said his fixed income team is betting that Treasury prices will decline, as the U.S. government issues more bonds while the Fed decreases its pace of bond buying.

Despite higher yields, “most investors still aren’t getting paid enough to hold U.S. government bonds for the long term,” Mr. Lawson said.

Updated: 4-23-2021

Bond Traders Are Falling For Treasuries Again

After the worst quarter in decades, yields are falling to key levels that may be difficult to crack.

U.S. Treasuries aren’t exactly an asset class that people should want to root for. Sure, there are any number of bond bulls who see ultra-low yields as a permanent fixture of a world beset by aging demographics and rapid technological change. But hoping for a strong and inclusive global economy, which I’d like to think most everyone wants to see, suggests a selloff in government-debt markets practically by definition.

Still, after the worst quarterly rout for the $21.4 trillion Treasury market since 1980, it’s hard to resist getting at least somewhat excited about momentum swinging the other way. The question that seems to be on every trader’s mind: Just how long can this possibly last? After all, the U.S. is still well on its way toward the strongest year of economic growth in decades.

And yet the benchmark 10-year yield fell to as low as 1.53% on Thursday, breaching its 50-day moving average for the first time in 2021 and returning to about the same level as a week earlier after a surprising and mysterious rally. Those gains were mostly chalked up to a combination of hedging flows caused by record-breaking bond sales from Bank of America Corp. and JPMorgan Chase & Co., signs of strong buying from Japanese investors and earnings that showed U.S. banks aren’t making enough loans relative to deposits, which potentially creates demand for fixed-income assets as an alternative. NatWest Markets strategist Blake Gwinn dubbed it “the little rally that could.”

Now that banks are done issuing debt, and currency-hedged Treasury yields are off their highs, there’s unease about what comes next. “We are at or near levels where we like to re-initiate shorts,” NatWest strategists wrote heading into the week. “We are willing to try and squeeze a few more bps out, also allowing a little more time to see if this move has a bit more momentum.” They recommended selling five-year notes at 0.75%, but the yield dipped only as low as 0.78% on Thursday before lurching higher.

Others aren’t so sure the trend is fleeting. “An increase in Covid cases globally has left investors focused on the path of the pandemic in India, Brazil, and other parts of the world,” Ian Lyngen at BMO Capital Markets noted on Thursday. “Unlike many sovereign rates markets, Treasury yields are far more directly influenced by global growth and inflation expectations as opposed to simply those for the U.S. specifically.” Getting the 10-year yield back to 1.75%, roughly the intraday high from late March, appears less likely than a move toward 1.5%, he said.

Then there’s Jim Vogel at FHN Financial, who has been tracking the amount of investor interest at given yield levels. He says it’ll take another two weeks for 10-year note trading volume in the mid-1.5% range to surpass the total in the mid-1.6% range. If there’s not enough demand at the lower rate, yields “should drift above 1.6% on a combination of lost momentum and boredom,” he wrote.

What should be clear is that bond traders desperately need something to shake up their conviction in either direction. The fact that technical forces have overwhelmed some of the most impressive economic data in recent memory supports the cliche that the “good news is already priced in.” To wit, Citigroup Inc.’s U.S. Economic Surprise Index is close to the lowest since early June after edging up for most of the first three months of the year as bond yields increased. Still, the prospect of an economic recovery remains very much a matter of when, not if, so a few stronger- or weaker-than-expected reports here and there don’t truly move the needle.

The Federal Reserve’s decision next week probably won’t provide much in the way of new information, either. However, the central bank’s preferred inflation gauge, the core personal consumption expenditure index, comes out two days later, with the median estimate in a Bloomberg survey pointing to 1.8% annual growth. A notably higher or lower reading could provide a jolt, given that it has remained below 2% for much of the post-2008 period and policy makers appear determined to change that.

As for the Bloomberg News report on Thursday that President Joe Biden will propose raising the capital gains rate to 39.6% for those earning $1 million or more, up from the current base rate of 20%: Treasuries took it mostly in stride. Longer-term yields dropped by about two basis points in the immediate aftermath as stocks tumbled from near-record levels. But raising revenue like this was always part of the administration’s plan. It’s shouldn’t come as a surprise that fiscal policy will be more restrained than it was during the heights of the coronavirus crisis.

Put together, Treasuries are at a crossroads. After Democrats won both U.S. Senate runoff elections in Georgia and 10-year yields broke through 1%, I wrote that bond traders still needed to determine whether more moderate party members would go along with a large fiscal stimulus plan (they did) and whether the U.S. could ramp up its vaccine rollout (it did). That rightfully pushed yields higher in a hurry.

But I also noted that once the country was mostly through the pandemic, the administration might impose stricter regulations and higher taxes on wealthy Americans and corporations. Both are starting to happen, from the Securities and Exchange Commission’s accounting crackdown on blank-check companies to the capital gains proposal.

All told, it’s tempting to say Treasuries can’t advance much more from here, choosing to believe that the coming recovery can justify a 10-year yield well above its current level, which pre-Covid would have been close to a record low. But “the little rally that could” just keeps chugging along.

Foreign Buying of U.S.,Foreign Buying of U.S.,Foreign Buying of U.S.,Foreign Buying of U.S.,Foreign Buying of U.S.,

Related Articles:

Treasury Expects To Issue Over $1 Trillion In Debt In 2018 (#GotBitcoin?)

Would Someone Please Buy US Treasury Bonds? (#GotBitcoin?)

U.S. Treasury Plans Increased Auctions to Fund Looming Trillion-Dollar Deficits (#GotBitcoin?

Debt-Market Slowdown Troubles Investors (#GotBitcoin?)

Your Questions And Comments Are Greatly Appreciated.

Monty H. & Carolyn A.

Go back

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.