A Retirement Wealth Gap Adds A New Indignity To Old Age (#GotBitcoin?)

Many middle-class Americans are financially unprepared for retirement—and that is leading to an array of social tensions. A Retirement Wealth Gap Adds A New Indignity To Old Age

Oakmont residents play pickleball—a game that’s like a gentler version of tennis, played with a paddle and a plastic ball with holes on a badminton-sized court.

Oakmont residents play pickleball—a game that’s like a gentler version of tennis, played with a paddle and a plastic ball with holes on a badminton-sized court.SANTA ROSA, Calif.—On a Saturday morning in retirement paradise, Ken Heyman stepped out to his front porch and found a brown paper bag. Inside was the chopped-off head of a rat.

Mr. Heyman was acting president of the homeowners’ association at Oakmont Village, an enclave in Northern California’s wine country for people age 55 and over. For months, the community had battled over the unlikeliest of topics: pickleball, a game that is a mix of tennis, badminton and ping pong. Some residents wanted to build a pickleball court complex that would cost at least $300,000. Others didn’t, saying they didn’t want to see their dues go up.

Residents shouted at each other at town-hall gatherings. One confrontation got so heated that a resident called the police. The governing board appointed a security guard to keep order at meetings.

For many, of course, the issue wasn’t really about pickleball. It was about a divide that had opened between wealthier residents who moved to the village more recently and the less well-off, who said clubhouse updates, new fees and expensive amenities would be budget-busters.

Mr. Heyman’s predecessor as president was a leader of the anti-pickleball faction. She felt she had been chased out of office by pickleball partisans. On the paper bag was a note.

“You’re next,” it read, according to a police report.

Around 10,000 baby boomers are turning 65 every day, and the same number will continue doing so for years. Some are on solid financial ground after a lifetime of planning and the fortune of well-timed home purchases and stock investments.

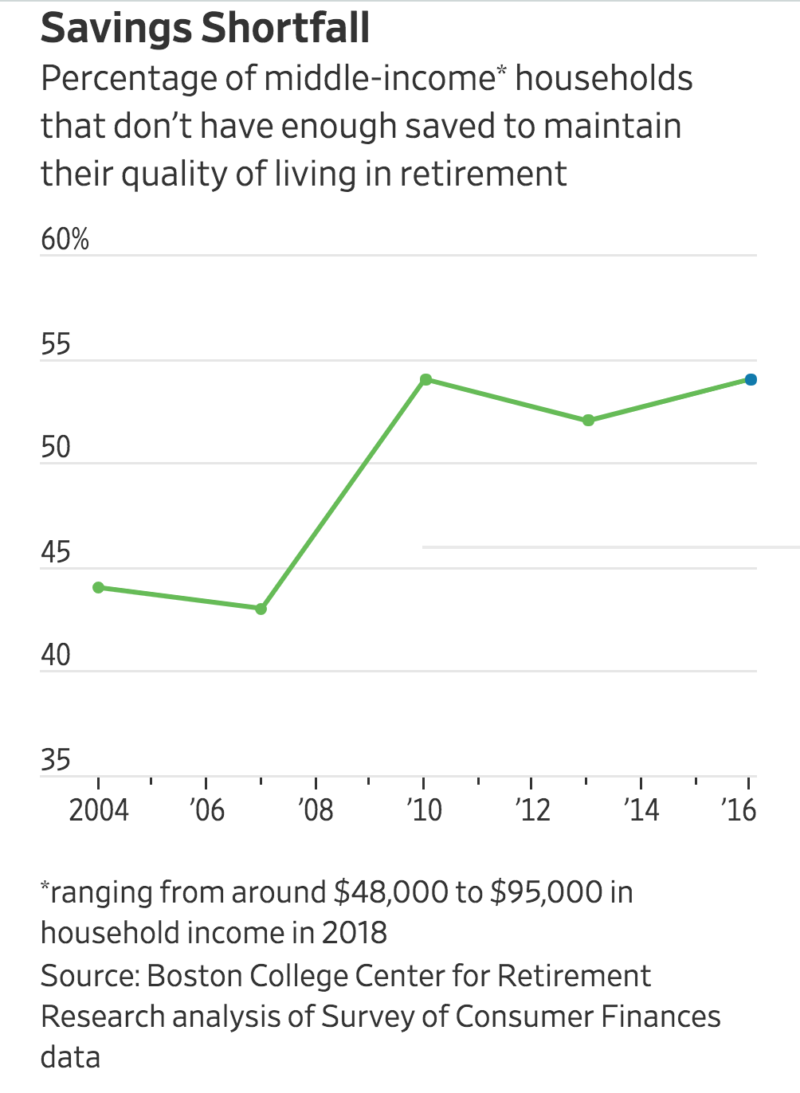

Most of the rest are unprepared. Fifty-four percent of households with middle incomes—ranging from around $48,000 to $95,000 a year—don’t have enough saved to maintain their quality of living in retirement, according to the Boston College Center for Retirement Research. Some of those who saved were hit by unforeseen health-care costs. Others took on debt for education. Yet more made investment mistakes or lost their savings in the 2008 financial crisis.

Those wildly different circumstances are leading to hard-to-resolve social tensions, which are playing out every day at retirement communities across the country. In Oakmont, the issue was pickleball.

Founded in 1963, Oakmont Village was long an option for the middle class that benefited from California’s rising real-estate values. They could move into attached duplexes or triplexes or wood-sided single-family ranch-style homes and enjoy three swimming pools, a lawn-bowling green, honor-system lending library and the 130-plus clubs and activities.

Living near one another is an increasingly popular option for retirees. The population of the U.S.’s 442 federally designated “retirement destination counties” rose 2% last year, compared with the national average of 0.7%, according to Census Bureau figures. Retirement communities often provide social connections that can fray when people leave the workplace, live alone or have families spread across the country.

Steve Spanier, the current president of Oakmont’s homeowners’ board, said the mountain-view community started “moving more upscale” in recent years when retiring baby boomers in San Francisco and Silicon Valley discovered it on weekend wine-tasting trips to Sonoma County. Coming from places where real-estate prices are especially high, they began buying and gutting homes. The community has about 4,700 residents.

Steve Spanier on the back deck of his home in Oakmont.

Steve Spanier on the back deck of his home in Oakmont.The community now splits neatly into two camps. Some believe it should only “fix things that break,” he says. “Then there are people like the people who are starting to move in. They have a lot of money and want to live the lifestyle to which they’ve become accustomed and they want to do it here,” he says. “People are having more trouble getting along.”

The October wildfires that tore through Northern California’s wine country last year fleetingly eased the divisions, says Mr. Spanier. The fires forced Oakmonters to temporarily evacuate and destroyed two of the village’s roughly 3,200 homes. The fitness center sold “Oakmont Strong” T-shirts, and the mood mellowed for a bit.

“It got better for a period of time,” he says, “then that feeling of unity created by the fire left.”

Homes in the resident-owned Oakmont Village fetch between $350,000 for smaller dwellings up to about $1.2 million for ranch-style homes that have been remodeled by wealthy newcomers. A few years ago, million-dollar sales were unheard of.

After retiring in 2015, Iris Harrell sold her part of the remodeling company she founded in Mountain View, Calif., and says she is “never going to have to worry about money.” She and her wife, Ann Benson, sold their home in Silicon Valley for $3.8 million and bought a hillside ranch-style home in Oakmont for about $800,000, she says.

They raised the roof to allow for windows tall enough for a view of the top of nearby Hood Mountain. So they can age at home, they installed an elevator and added 1,300 square feet of space, including a spacious wing that could house a live-in caretaker. Ms. Harrell now calls the wing “the best guest suite in Oakmont.”

“We’re spoiled and we know it, but it just worked out for us,” says the fit 71-year-old.

She became the chairwoman of Oakmont’s building construction committee and set about trying to also refurbish the 55-year-old community.

Iris Harrell installed an elevator and added 1,300 square feet of space to her Oakmont home.

Iris Harrell installed an elevator and added 1,300 square feet of space to her Oakmont home.

“You can’t be premier and look like the 1960s,” Ms. Harrell says. “It’s not making the statement we want.”

She says that retirees moving in—“post Google-ites” she calls them—are willing to pay for better amenities and that Oakmont’s future shouldn’t be dictated by the “small minority” who aren’t willing. She suggested those pinched for money should look into a reverse mortgage.

Oakmont resident Gary O’Shaughnessy, who lives in a unit of a triplex down the hill from Ms. Harrell’s house, calls that suggestion “insensitive.”

“That attitude I can’t live with,” he says.

A former school-bus driver for disabled children, Mr. O’Shaughnessy says a diagnosis of Parkinson’s led him to retire in his 60s, earlier than planned.

While he was working, he rented a house in Santa Rosa. He bought his place in Oakmont for $280,000 in 2010 with help from an inheritance from his mother and $50,000 from his own retirement account. He is single and 71 and has $40,000 in savings. His monthly income is around $2,000, from Social Security and a small pension.

He says he typically walks dogs seven days a week to “make ends meet”; his bills include a mortgage, supplemental medical insurance and more than $300 in monthly dues at Oakmont.

Gary O’Shaughnessy has started dog-walking to ‘make ends meet,’ he says.

Gary O’Shaughnessy has started dog-walking to ‘make ends meet,’ he says.

Everyone in the resident-owned community pays $67 a month per person to the main Oakmont association, up from $58 last year. Households pay another $220 a month, on average, to various sub-neighborhood associations for services such as water or landscaping.

Mr. O’Shaughnessy started attending meetings and signing petitions as plans, backed by Ms. Harrell and others, proceeded for a roughly $300,000 tournament-quality pickleball complex with tiered spectator seating.

“There was a big fight and it kind of divided the community,” he says. “The people who have money just want to throw it around, but there are a lot of people on fixed incomes.”

A 2015 survey sponsored by the Oakmont association found that 48% of residents said they were very or somewhat concerned about their current financial needs. That figure rose to 57% for those under age 66.

Overall, 52% were “not at all concerned.”

“We are an extremely wealthy community,” resident Vince Taylor, a former software-company owner, said, during an open forum at an association meeting in March 2017. “We shouldn’t be acting like a poverty community.”

Vince Taylor in his backyard garden in Oakmont.

Vince Taylor in his backyard garden in Oakmont.Mr. Taylor, who is 81 and retired, says he has more than $1 million in his retirement savings and lives off investment earnings without touching the principal.

His public comments provoked discussion on Nextdoor, an online neighborhood social-networking service. A discussion titled “Disparity of wealth in Oakmont” drew nearly 80 comments.

One Oakmont resident suggested retirees with tight budgets get jobs. Another, Bob Starkey, a 69-year-old renter and retired museum director, wrote that illness had depleted his savings and that he lived with anxiety his car might die.

“Please remember that pensions have become a thing of the past,” wrote Margaret Babin, a retired home-day-care operator who is 62 and is selling her collection of French Quimper pottery on eBay to pay for extras.

“At some events, I feel out of place even though I shouldn’t, because I’m doing OK,” she says, noting that she sees more fancy cars in the community. “The separation seems to be getting wider and wider.”

By early 2017, she and other frustrated residents had organized behind a slate of candidates who aimed to win a majority on the homeowners’ board and halt the pickleball project, which had been approved by Oakmont leaders but not yet built.

On the morning of April 3, a phone call woke up Ms. Babin. “I just couldn’t believe what I was hearing,” she recalls.

One day before the votes would be tallied in the election, a bulldozer was breaking ground on the pickleball complex. Supporters and detractors rushed over. One resident called the Santa Rosa Police Department at 7:24 a.m. to report a “verbal disturbance” at Oakmont.

“There is a heated argument going on at this time,” the police report said. An officer who went to the scene wrote that there were “two warring factions over a pickleball court.”

The next day, the candidates opposing the pickleball complex were victorious. Construction stopped.

“We face some of the same challenges as the rest of our state and our country,” Ellen Leznik, the new president, said at a public association meeting days later. “One such challenge is the disparity of wealth in our membership.”

Some pickleball proponents rose to defend themselves.

“We’re not the mean, vicious and entitled people our opponents and Nextdoor critics would have you believe,” one speaker said.

Oakmont eventually converted two existing tennis courts into six pickleball courts at a fraction of the cost. The new board ushered in a tone of frugality and oversight that some saw as heavy-handed. Rhetoric at public meetings grew so hostile that the board brought in a security guard to keep order.

“Why don’t we just wait till we’re all dead?” an Oakmont man who favored the pickleball complex declared at one meeting. “Guess what? Oakmont is our last stop. The train ends here. This is the Hotel California.”

Oakmont’s activities include a popular swimming aerobics class.

Oakmont’s activities include a popular swimming aerobics class.

Resident Charlotte Martin on the patio of her duplex unit home.

Resident Charlotte Martin on the patio of her duplex unit home.

Resident Nancy O’Brien outside her triplex ranch-style home.

Resident Nancy O’Brien outside her triplex ranch-style home.

Ms. Leznik, a 60-year-old former lawyer who retired early because of a disability, resigned less than four months after she became president, in July 2017. She says she had heart palpitations from the stress.

That left her ally, Mr. Heyman, as acting president.

The next month, at 9:15 a.m. on Aug. 12, the police again got a call from Oakmont, this time from Mr. Heyman, who is 61 and still works in corporate communications.

On Mr. Heyman’s porch sat “a bag containing the chopped off head of a rat,” according to the police report.

“It freaked me out,” says Mr. Heyman. He says he has “no doubt” the rat served as retribution for killing the pickleball project and for the disputes that followed.

At an association meeting soon after, another board member likened “the battle being waged at Oakmont” to “Armageddon.”

Mr. Heyman left the board and later moved out of Oakmont.

“There were clearly sides. One side felt that we’re an active-adult community and it’s our responsibility to provide activities and facilities to the membership,” says Oakmont resident Al Medeiros, 71, who now sits on the board. He counts himself in that group, which he says had been “vilified.”

Al Medeiros counts himself among residents who believe the community should provide activities and facilities.

Al Medeiros counts himself among residents who believe the community should provide activities and facilities.

“The other side seemed to think that well, we’re poor, so we really need to make sure our dues don’t go up and we should just provide the minimum,” he says.

In February, the board discussed remodeling a dated auditorium where hundreds of events, from dances to movies to meetings, take place every year. Some residents talked about constructing a new center and repurposing the old one into a state-of-the-art gym.

The board is also weighing a divisive request from the private golf club that borders many homes in the retirement community. The club is asking all Oakmont residents, golfers or not, to pitch in to help the club meet economic challenges. Someone suggested $5 a person every month.

Mr. Spanier, the new board president, says it “could potentially make pickleball look like a tiny issue.”

A Generation of Americans Is Entering Old Age The Least Prepared In Decades

Low incomes, paltry savings, high debt burdens, failed insurance—the U.S. is upending decades of progress in securing life’s final chapter.

Americans are reaching retirement age in worse financial shape than the prior generation, for the first time since Harry Truman was president.

This cohort should be on the cusp of their golden years. Instead, their median incomes including Social Security and retirement-fund receipts haven’t risen in years, after having increased steadily from the 1950s.

They have high average debt, are often paying off children’s educations and are dipping into savings to care for aging parents. Their paltry 401(k) retirement funds will bring in a median income of under $8,000 a year for a household of two.

In total, more than 40% of households headed by people aged 55 through 70 lack sufficient resources to maintain their living standard in retirement. That is around 15 million American households.

Things are likely to get worse for a broader swath of America. New census data released this week shows the surge of aging boomers is leaving the country with fewer young workers to support the elderly.

Individuals will find themselves staying on the job past 70 or taking menial jobs as senior citizens. They’ll have to rely more on children for funding, pressuring younger generations, too.

Companies, while benefiting from older workers’ experience, also have to grapple with employees who delay retirement, which means they’ll be footing the costs of a less healthy workforce and retraining older workers.

And for the nation, the retirement shortfall portends a drain on public resources, especially if seniors reduce taxable spending and officials decide to cover additional public-assistance costs for older Americans who can’t make ends meet.

“This generation was left on their own,” said Alicia Munnell, director of the Boston College Center for Retirement Research. The Journal’s conclusion about living standards in retirement was based on estimates provided by Ms. Munnell’s center and data from the U.S. Census.

As with many baby boomers, 56-year-old Kreg Wittmayer once thought he was doing things right for a solid retirement. In his 20s, he began saving in his 401(k). He cashed it out after a divorce at age 34. He built up the fund again, then cashed out five years later after losing his job, he says. “It was just too easy to get at.”

Mr. Wittmayer, of Des Moines, Iowa, says he now has a little over $100,000 saved for retirement. He owes $92,000 in parent loans for his daughters’ college costs, he says. He doesn’t know when, or whether, he will be able to retire, in direct contrast to his parents, a former firefighter and a former teacher who collect guaranteed pensions. “They never had to worry about saving for their retirement.”

This prospect is upending decades of progress in financial security among the aging. In the postwar era, for a while, fixed government and company pensions gave millions a guaranteed income on top of Social Security. An improving economy led to increased wages. Many Americans retired in better shape than their parents.

No more. Baby boomers were the first generation of Americans who were encouraged to manage their own retirement savings with 401(k)s and similar vehicles. Many made investing mistakes, didn’t sock enough away or waited too long to start.

Consider:

• Median personal income of Americans 55 through 69 leveled off after 2000—for the first time since data became available in 1950—according to an analysis of census data done for the Journal by the Urban Institute, a nonprofit research organization that has published research advocating for more government funding for long-term care. Median income for people 25 through 54 is below its 2000 peak, but has edged up in recent years, and younger workers have more time to adjust retirement-savings strategies.

• Households with 401(k) investments and at least one worker aged 55 through 64 had a median $135,000 in tax-advantaged retirement accounts as of 2016, according to the latest calculations from Boston College’s center. For a couple aged 62 and 65 who retire today, that would produce about $600 a month in annuity income for life, the center says.

• The percentage of families with any debt headed by people 55 or older has risen steadily for more than two decades, to 68% in 2016 from 54% in 1992, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute, a nonpartisan public-policy research nonprofit.

• Americans aged 60 through 69 had about $2 trillion in debt in 2017, an 11% increase per capita from 2004, according to New York Federal Reserve data adjusted for inflation. They had $168 billion in outstanding car loans in 2017, 25% more per capita than in 2004. They had more than six times as much student-loan debt in 2017 than they did in 2004, Fed data show.

Shortfall Generation

A combination of economic and demographic forces have left older Americans with bigger bills and less money to pay them.

Tempted by a prolonged era of low interest rates, boomers piled on debt to cope with rising home, health-care and college costs. Interest-rate declines hurt their security blankets. Lower earnings on bonds prompted many insurance firms to increase premiums for the universal-life and long-term-care insurance many Americans bought to help pay expenses. Some public-sector workers are living with uncertainty as cash-strapped governments consider pension cuts.

Gains in life expectancy, combined with the soaring price of education, have left people in their 50s and 60s supporting adult children and older relatives. Some are likely to have to rely on professional caregivers, who are in short supply and are more expensive than informal arrangements of the past.

Then there are health-care costs. Since 1999, average worker contributions toward individual health-insurance premiums have risen 281%, to $1,213, during a period of 47% inflation, according to the nonprofit Kaiser Family Foundation. Nearly half of 1,518 workers surveyed last June by the Employee Benefit Research Institute said their health-care costs increased over the prior year, causing more than a quarter to cut back on retirement savings, and nearly half to reduce other savings.

Only a quarter of large firms offer retiree medical insurance, which typically covers retirees before they become eligible for Medicare, down from 40% in 1999, according to Kaiser. More money is coming out of people’s Social Security checks to pay for Medicare premiums and costs that the federal program doesn’t cover, Kaiser says. Medical spending accounted for 41% of the average $1,115 monthly Social Security benefit in 2013, and the percentage has likely risen since, it says.

Unexpected health costs have taken a toll on Sharon Kabel, 66, of East Aurora, N.Y. She already had trouble making ends meet after a yarn shop she owned for about 15 years failed in 2017. Then she suffered a heart attack this year.

In the store’s heyday, she employed three part-time workers. On Friday evenings, customers gathered to knit over cookies and wine. “I was like a bartender. People would come in and tell me about their children and their problems,” she says. Many customers eventually defected to the internet.

Her Social Security check is barely enough to cover the $800 monthly mortgage on the house she bought after a divorce settlement 11 years ago. She brings in another $800 a month cleaning houses, baby-sitting, walking dogs and selling yarn stored in her basement, she says. She grows vegetables and cans them for the winter.

She just started working three days a week at a garden center, a job she says will last until winter. “I live frugally. I don’t get my hair cut or go on vacations, and I drive a 12-year-old car.”

After a hospitalization, Ms. Kabel relied on friends and relatives for help. Some brought food and gift cards. Because Ms. Kabel skipped a Part D drug plan when she signed up for Medicare last year, one of her five children paid the $173 monthly cost of one prescription, she says. Another paid a $350 heating bill.

She has since secured drug coverage but owes $10,000 in credit-card debt. As a shop owner, she never earned enough to set up a tax-advantaged retirement plan.

Pension Retreat

For many Americans facing a less secure retirement than their parents, the biggest reason is the shift from pensions to 401(k)-type plans.

A piano and organ maker in the 1880s launched one of the first employer-sponsored pension plans, and railroads, state and local governments, and others followed, according to the Social Security Administration. By the 1930s, about 15% of the labor force had employer pensions.

In 1935, federal officials created Social Security to offer a basic income. Pensions gained steam after World War II, and by the 1980s, 46% of private-sector workers were in a pension plan, according to the Employee Benefit Research Institute.

A seemingly small congressional action in 1978 set the stage for a pension retreat. Some companies had sought tax-deferred treatment of executives’ bonuses and stock options to supplement their pension payouts, and Congress authorized the move. The tax-law change ushered in the 401(k), allowing employees to reduce their taxable income by placing pretax dollars in an account.

In the 1980s, union strength was ebbing and a recession pressured employers to reduce pension funding, says Teresa Ghilarducci, an economics professor at the New School. Many employers deployed the 401(k) to displace pensions.

Market declines in 2000 and 2008 revealed the perils of do-it-yourself retirements, as many 401(k) participants cut back on contributions, shifted funds out of stocks and never put them back in, or withdrew money to pay bills.

Arthur Smith Jr., 61, is still feeling the impact. He consistently saved in 401(k)-type plans with various employers over the past 35 years, he says. His 401(k) got hit hard in the market crashes, he says, in large part because he invested in individual tech stocks.

“We were allowed to pick our own stocks and I jumped on some high-risk ones,” he says. His 401(k) lost about half its value early in the 2000s and lost about half again in 2008, he says. “We didn’t plan it right and lost a few times.”

He and his wife, Connie, 56, withdrew about $25,000 from the account to buy a house last year when he was transferred to Houston from New York. The account is down to about $20,000, they say, and they haven’t been able to sell their New York home, so they have two mortgages.

He has a pension from a decade working at a large corporation that he expects will generate about $500 a month. Combined with Social Security, he could earn about $3,000 a month in retirement income at age 66, which he says isn’t enough. “My ideas of retiring are gone.”

Others have been diligent savers but lacked knowledge to manage their money. “You don’t have a lot of people to coach you how to invest,” says Parline Boswell, 63, of New York City. She saved $5,000 during several years as a housekeeper in the 1990s while raising three children.

In 1998, she went to a bank for investing advice and ended up with a money-market account, which earned minimal income until 2007. She had become a hospital phlebotomist and in a conversation with colleagues learned about tax-advantaged investing.

She says she now has about $30,000 in a 403(b), a cousin to the 401(k). “That’s not enough,” she says. “I’m still working and trying to catch up.” She also helps with expenses for her mother, aged near 100, and anticipates working until 70.

Recognizing the 401(k)’s shortcomings, Congress in 2006 enacted legislation making it easier for employers to enroll employees automatically and put them into funds that shift focus from stocks to bonds as they age. Almost a dozen states have authorized state-run retirement-savings programs to cover some of the estimated 55 million private-sector workers without workplace plans, according to AARP, the advocacy group for older Americans.

Those safeguards generally came too late for Americans now in their 60s, including Linda McCord, 69, of Denison, Texas. After 15 years as a manager at a consumer-lending firm, she took a lump-sum pension payment in the late 1980s following the sale of the business, she says. None of the finance or banking jobs she held after that offered a pension.

She wasn’t concerned about her retirement because her husband had hundreds of thousands of dollars in a profit-sharing plan. She did have a 401(k) at a mortgage-origination firm in the early 2000s, but its balance was small when she left the workforce in 2003 due to health problems.

Her husband, Rusty, 63, followed in 2011 after a factory closing. They lived off her Social Security Disability Income for a couple of years and spent much of the money in his profit-sharing plan. They now live on her Social Security and his disability payments.

Rusty and Linda McCord going through unpaid bills and on their front porch. Ms. McCord’s medications.

Rusty and Linda McCord going through unpaid bills and on their front porch. Ms. McCord’s medications.

Money tight, Ms. McCord says she is selling parts of a collection of Star Trek action figures, dolls, yo-yos, lunchboxes and a book autographed by actor Leonard Nimoy.

She also struggles with another higher cost for her age group: life-insurance premiums. The annual premium on a policy she has owned since 1994 more than tripled over the past two years, she says, to about $2,000 this year. “I just want to scream bloody murder,” she says. “It is hurting so bad.”

She wants the $100,000 policy to pay for her funeral, to extinguish debts and to “hopefully have a little for our grandkids” left over.

Related Articles:

The $210 Billion Risk In Your 401(K) (#GotBitcoin?) THURSDAY, OCTOBER 11, 2018 AT 1:11 PM

401(K) Or ATM? Automated Retirement Savings Prove Easy To Pluck Prematurely (#GotBitcoin?) SATURDAY, AUGUST 11, 2018 AT 11:47 AM

401(K) Rule Change Would Ease Small Companies’ Path To Joint Plans (#GotBitcoin?) SATURDAY, OCTOBER 27, 2018 AT 7:14 AM

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.