Washington Has Learned To Love Debt And Deficits (#GotBitcoin?)

Political support for taming federal debt has melted away, and the U.S. is testing just how much it can borrow. Washington Has Learned To Love Debt And Deficits (#GotBitcoin?)

William Hoagland has engaged in nearly every Washington budget-deficit battle for four decades. A longtime analyst and onetime senior Republican congressional budget aide, he brought a sensibility learned growing up on an Indiana farm: You’ve got to balance the books over time.

He feels like a voice in the wilderness now.

The theories about debt and deficits and whether they matter—once widely shared in Washington, on Wall Street and in academia—have fundamentally changed.

Political support for taming deficits has melted away, with Republicans accepting bigger deficits in exchange for tax cuts and Democrats making big spending promises around 2020 election campaigns. Global demand for U.S. Treasury assets has displaced the “bond-market vigilante” mentality of the 1990s that scared Washington.

Leading scholars, in a mini-revolution hitting academia, are debating whether large federal debt and deficits might be tolerable. They aren’t a top concern for voters anymore, either.

Even some former deficit hawks say rising government red ink might not be the grave problem they once believed.

The new bottom line: The U.S., despite a record-long economic expansion, is on course to test just how much it can borrow.

“I’ve thought it’s time to box up all these budgets surrounding me right here and going back to the farm and forgetting all about it,” says Mr. Hoagland, a senior vice president at the Bipartisan Policy Center, who remains a deficit hawk and thinks the rising red ink will end badly. “It’s almost like I’ve wasted my, whatever it’s been, 45 years in this town.”

Debt as a share of economic output has more than doubled over the past decade. Deficits, after falling in the expansion’s first six years as a share of the economy, are rising again, approaching $1 trillion a year.

In theory, an increased supply of government bonds—sold to raise funds when spending exceeds revenues—should increase government borrowing costs. Theory also says big deficits crowd out business borrowing and increase private borrowing costs, too.

The opposite has happened. While government debt soared after the 2007-2009 financial crisis, 10-year Treasury yields have fallen to near 2% from more than 5% in 2006, holding down government interest payments. U.S. business debt rose to $15 trillion in 2018 from $9 trillion in 2006.

Debt isn’t catastrophic, says Olivier Blanchard, former International Monetary Fund chief economist. “If you have good uses for it, use it.”

The U.S. government borrowing cost has tended since World War II to be less than the economy’s growth rate, he said in the keynote address at the American Economic Association’s annual meeting in January. The profound implication: Government borrowing might cover its costs over time if the economy keeps growing.

Last year, economic output grew 5.2%, not adjusted for inflation, while 10-year Treasury yields never exceeded 3.25%. Mr. Blanchard, the association’s former president, says he is rewriting the fiscal-policy chapter of his macroeconomics textbook.

“Olivier Blanchard is basically saying there is a free lunch,” says Valerie Ramey, a University of California, San Diego, fiscal-policy expert and one of a shrinking number of voices leery of dangers down the road.

Her research shows government-funding costs tend to decline during wartime when spending increases, jibing with Mr. Blanchard’s work. But she worries that past relationships will lose power once policy makers try exploiting them.

“We don’t know how long the real interest rate is going to stay this low,” she says. “It could suddenly start increasing, and the U.S. could be left in a really bad situation if it has a lot of debt to finance.”

The Congressional Budget Office, which expects the average interest cost on debt to rise to 3.5% over the next decade from 2.3%, estimates the government will spend more on interest in 2020 than on Medicaid and more in 2025 than on national defense.

A recession would test how much debt the government is prepared to accumulate. Spending on safety-net programs like unemployment insurance rises during recessions, and tax receipts fall. Policy makers are pressured to increase spending or cut taxes to stimulate growth—so when the economy sinks, already large deficits will soar.

Countries with high debt before crises have weaker recoveries, partly because policy makers pull back on stimulus quickly for fear of pushing debt levels too high, found University of California, Berkeley, economists Christina Romer and David Romer.

Robert Rubin, who as Treasury Secretary pushed President Clinton for deficit reduction, says bond markets are out of sync with the economy. A reset in investor views could become a “real problem” for America, he says. “To believe in free lunches isn’t a very sound basis for policy.”

In The Black

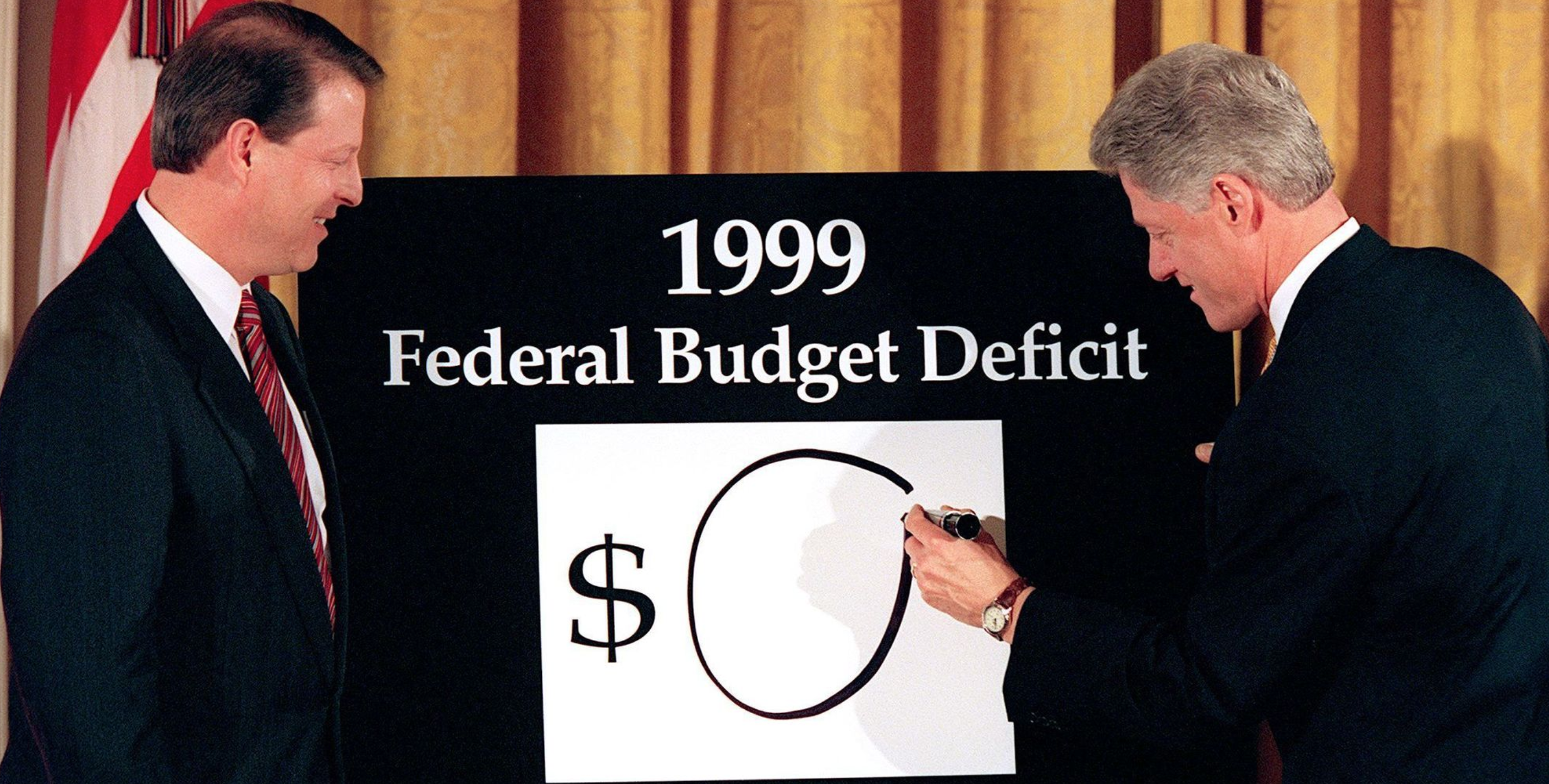

The federal government has run deficits in all but four of the past 50 years. Budget deals during the George H.W. Bush and Clinton administrations, which included tax increases on high-earning Americans, and spending cuts, plus economic growth, put the budget in the black in 1998 for the first time since 1969.

Smaller deficits meant lower interest rates that stimulated spending and investment. Yields on 10-year Treasurys fell from near 9% in 1990 to under 5% by 1998. The CBO projected annual surpluses for the next 10 years.

But recession hit in 2001. Republicans cut taxes, and America spent on wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. A financial crisis, and another recession starting in 2007, led to bank bailouts, safety-net-program spending and hundreds of billions in fiscal stimulus. Publicly held debt swelled to 76% of gross domestic product in 2016 from 32% in 2001.

A political movement to tame deficits proved short-lived after Tea Party Republicans poured into Congress in 2010 decrying debt. They pressed President Obama to cut discretionary spending. He forced Republicans to accept increased top tax rates. Deficits began receding, but neither side could reach agreement to rein them in long-term.

“I’m the master of lost causes,” says Alan Simpson, former Republican senator from Wyoming, who in 2010 co-headed a commission Mr. Obama created to make deficit-reduction recommendations. Mr. Obama didn’t endorse his proposals, and none of his recommendations saw a Congressional vote. “Everyone out there just began to pick it apart,” he says of the plan he co-wrote with Democrat Erskine Bowles.

Donald Trump campaigned in 2016 promising to eliminate the $19 trillion national debt in eight years but offered policies cutting taxes and increasing military spending, and a vow not to cut entitlement-spending programs.

Debt kept rising under his leadership and with Republicans in control of Congress.

Political will vanished partly because there was no discernible effect on bonds. Yields on 10-year Treasurys have rarely poked above 3% in this economic expansion. Theory says inflation should rise with government borrowing, but it fell. In response, the Federal Reserve became a big market player, buying nearly $2 trillion in long-term government bonds.

Foreign investors flocked to U.S. bonds as safe investments relative to alternatives. Foreign holdings of Treasury securities grew to over $6 trillion in 2018 from $1 trillion in Dec. 2000.

“There are plenty of savings around the world to be invested,” says former Federal Reserve Bank of New York President William Dudley.

Today, few Republicans or Democrats exhibit much interest in reducing deficits. Republicans cut taxes in 2017 and agreed with Democrats in 2018 to boost spending on the military and domestic programs nearly $300 billion above spending caps set during 2011 deficit battles. Both parties are now negotiating whether to bust those caps again this year.

“If the markets were overwhelmingly worried about our budgets and our spending and our deficits, you would see that interest rate rise,” Lawrence Kudlow, director of Mr. Trump’s National Economic Council, told Fox News in March.

White House chief of staff Mick Mulvaney, a deficit hawk in Congress during the Obama years, at an April conference said the national debt “doesn’t seem to be holding us back from an economic standpoint.” At a Wall Street Journal event Tuesday, he said Mr. Trump wants to reduce deficits but there isn’t enough political support in either party to curb spending.

GOP lawmakers see higher deficits from tax cuts as a trade-off for stronger growth they say will fill the budget shortfall long-term. To control deficits, they argue for spending cuts. Democrats reject that argument, saying Republicans raised deficits after criticizing them in the Obama era.

“They passed a $2 trillion tax cut,” says Rep. Barbara Lee (D., Calif.). “And they are using the argument that we don’t have the resources as a need to cut budgets. We’re not going to let them do that.”

Rep. Tom McClintock (R., Calif.) says many House Republicans care about deficits but efforts to rein them in never gained traction among GOP leadership—even when it controlled both chambers. “I think it’s a tremendous opportunity for the Democrats,” he says, “to step forward, bring our spending under control while there’s still time, and show the Republicans up.”

‘Why Worry?’

A January Pew Research Center survey found 48% of Americans—54% of Republicans, 44% of Democrats—said deficit-reduction should be a priority, compared with 72% in 2013 at the start of Mr. Obama’s second term.

Rep. John Yarmuth (D., Ky.), House Budget Committee chairman, says he rarely hears from constituents concerned about rising deficits and debt. Many voters’ attitudes, he says: “There haven’t been any cataclysmic consequences, so why worry about it?”

After taking House control this year, Democrats considered a resolution holding deficits steady as a share of the economy over 10 years. They abandoned it after progressive lawmakers signaled they wouldn’t support a budget without major spending initiatives, such as a Green New Deal and Medicare for All.

“The deficit hawk wing of the Democratic Party has just lost a tremendous amount of power,” says Douglas Elmendorf, dean of the Harvard Kennedy School of Government. One reason, he says: It sought compromise with Republicans who abandoned deficit control once in power.

As an economic adviser in the Clinton White House and Treasury Department, he sought smaller deficits. Mr. Elmendorf, CBO director from 2009 to 2015, now is among economists who argue deficits aren’t the threat they once believed because interest rates have proven persistently low.

Though debt has soared as a share of GDP, government interest payments have fallen to 1.6% of GDP last year from 3% in 1989, says Jason Furman, chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers under Mr. Obama. “Talk about climate change, talk about jobs, talk about all the things you want to do,” he says. “Then just have the deficit in the background as something you’re not going to make worse.”

Messrs. Furman and Elmendorf say they worry the argument can go to extremes, including a concept many Democrats have warmed to, called Modern Monetary Theory. It holds that the U.S. government can always create more money to fund itself, only stopping if that creates inflation. “Some are taking this too far,” says Mr. Furman.

Moody’s Investors Service in December warned that, while the U.S. maintains a triple-A credit rating, “rating pressures could emerge in the coming years in the absence of a shift in fiscal policy to reduce the government’s budgetary imbalances and stabilize debt metrics.”

Moody’s projects that within a decade interest payments will consume over 20% of federal revenue, well above most other developed nations and exceeding U.S. levels in the 1980s and 1990s when debt worries consumed Wall Street and Washington.

Former Sen. Simpson, retired in Wyoming, anticipates a reckoning: “If you spend more than you earn, you lose your butt.”

Updated: 11-14-2019

Got Bitcoin? US Fed Warns National Debt Growth Is ‘Not Sustainable’

The head of the United States Federal Reserve has admitted current economic policy is “not sustainable” — but that it is not its job to fix it.

Speaking during testimony before Congress’ Joint Economic Committee on Nov. 13, Jerome Powell noted that currently, U.S. national debt is growing faster than nominal GDP.

Powell: Solving debt spiral “not up to the Fed”

“Ultimately in the long run that’s not a sustainable place to be,” he said. Powell continued:

“How to fix that — it’s easy to say that — how do you do that and when do you do that is an issue that is up to you and not to us.”

As Cointelegraph reported, U.S. debt has now topped $23 trillion — around $70,000 per head of the population, or more than $1 million for each Bitcoin that will ever exist.

On the night of Nov. 14 alone, the Fed distributed funds to banks worth 12.7 million BTC, while its balance sheet is expanding towards $4 trillion.

For Powell, however, resolving the debt crisis simply means making growth beat debt, and even failure to do so would not equal chaos.

“I would be remiss in not pointing out that the consequences of not addressing it is just that… our kids and grandkids will be spending their tax dollars servicing debt rather than on the things they really need,” he continued.

Trump wants negative interest rates

The comments came as U.S. president Donald Trump renewed calls for negative interest rates — effectively charging savers to store fiat currency — and criticized the Fed for not introducing them.

“Remember, we are competing with nations who openly cut interest rates so that now many are actually getting paid when they pay off their loan… who ever heard of such a thing? Give me some of that, give me some of that money,” he said in a speech to the Economic Club of New York.

Debt-driven economic policy and its consequences were the main motivation behind Bitcoin (BTC), which appeared after the 2008 economic crisis.

As hard money with a deflationary supply impossible to manipulate, Bitcoin is increasingly compared to gold as a hedge against the constant erosion in the value of fiat currencies.

Washington Has Learned To,Washington Has Learned To,Washington Has Learned To,Washington Has Learned To,Washington Has Learned To,Washington Has Learned To,Washington Has Learned To

Related Articles:

Trump Calls On Fed To Cut Interest Rates, Resume Bond-Buying To Stimulate Growth (#GotBitcoin?)

Fake News: A Perfectly Good Retail Sales Report (#GotBitcoin?)

Anticipating A Recession, Trump Points Fingers At Fed Chairman Powell (#GotBitcoin?)

Affordable Housing Crisis Spreads Throughout World (#GotBitcoin?) (#GotBitcoin?)

Los Angeles And Other Cities Stash Money To Prepare For A Recession (#GotBitcoin?)

Recession Is Looming, or Not. Here’s How To Know (#GotBitcoin?)

How Will Bitcoin Behave During A Recession? (#GotBitcoin?)

Many U.S. Financial Officers Think a Recession Will Hit Next Year (#GotBitcoin?)

Definite Signs of An Imminent Recession (#GotBitcoin?)

What A Recession Could Mean for Women’s Unemployment (#GotBitcoin?)

Investors Run Out of Options As Bitcoin, Stocks, Bonds, Oil Cave To Recession Fears (#GotBitcoin?)

Goldman Is Looking To Reduce “Marcus” Lending Goal On Credit (Recession) Caution (#GotBitcoin?)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.