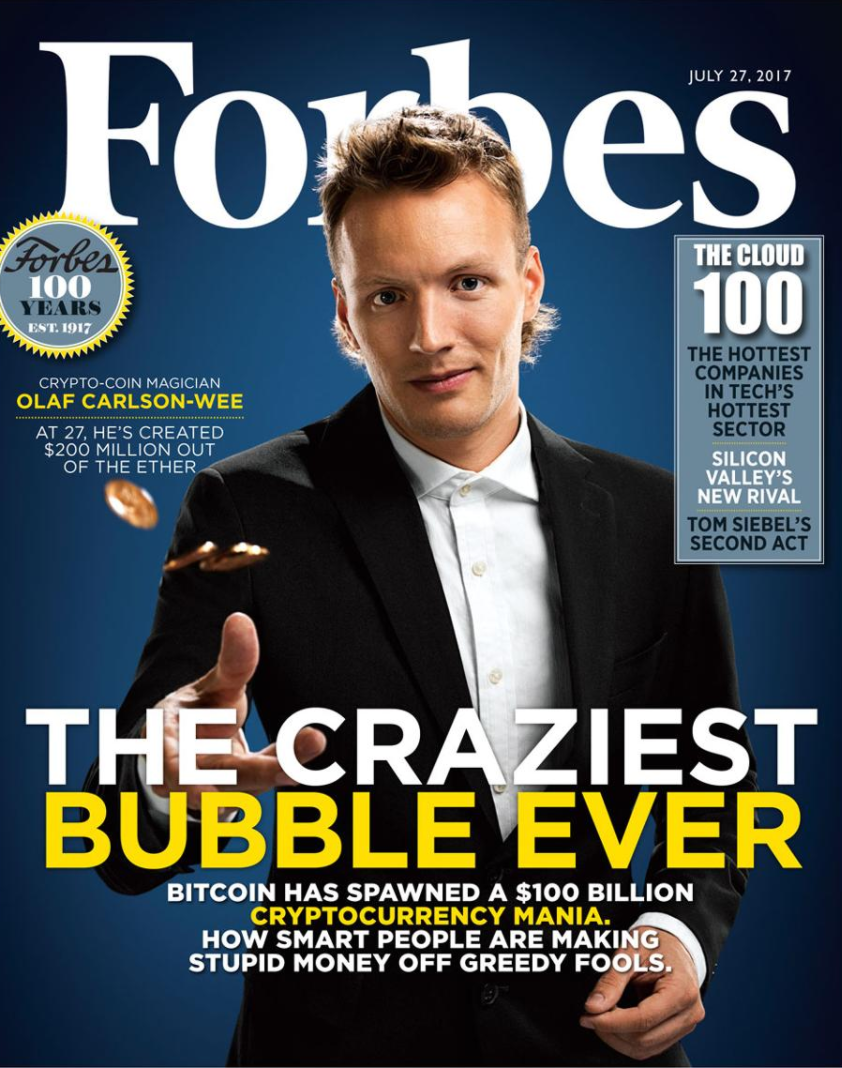

Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The Bitcoin Boom To Silicon Valley Riches. Can He Survive The Crash? (#GotBitcoin?)

Now running the world’s largest crypto hedge fund, the 29-year-old says he is undeterred by recent losses. Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The Bitcoin Boom To Silicon Valley Riches. Can He Survive The Crash?

SAN FRANCISCO—Olaf Carlson-Wee has crammed the highs and lows of a hedge-fund career into roughly one year—all before his 30th birthday.

Now, Mr. Carlson-Wee must prove he isn’t a one-hit wonder. It isn’t going well.

Polychain has shed around 40% of the $800 million it made for clients last year through a combination of investment losses and withdrawals by some of its earliest investors. Some backers grumble that Mr. Carlson-Wee refuses to change tactics despite a broad pullback from crypto. Mr. Carlson-Wee cashed out a big chunk of his personal haul in the fund months ago.

Prominent venture-capital firm Union Square Ventures has yanked some of its money, while others have fallen out privately with the firm. One investor is suing, suspecting he was underpaid when he moved to redeem his investment. Attorneys for Polychain and Mr. Carlson-Wee deny that.

Crypto fever, meanwhile, has broken. After capturing the attention of the investing world in 2017, bitcoin, the most well-known of a mushrooming collection of so-called digital assets, is down 55% this year. It recently traded for $6,301, down from its peak of nearly $19,280 in December.

Crypto Crash

Bitcoin and cryptocurrency competitor Ethereum have fallen sharply in value.

“How much of it is luck, how much of it is skill and how much of it is luck disguised?” asks Fred Ehrsam, one of Polychain’s first investors, who is now starting his own fund.

At the center of the maelstrom is Mr. Carlson-Wee, a Silicon Valley star who wears neon tracksuits, has five earrings and routinely eats only a plate of refried beans, garlic and cheese for dinner. He is treated as an oracle by wannabe cryptocurrency moguls who mob him in public.

In interviews, he compared his relationship with cryptocurrency to romantic love, and likened the current investment opportunity to the early days of the internet.

Through each dip downward, he has continued buying, particularly stakes in businesses tied to bitcoin rivals such as the cryptocurrency ether. He manages Polychain’s roughly $650 million flagship fund—the world’s biggest in crypto—from an Apple laptop surrounded by vintage boom boxes in undisclosed, secret San Francisco warehouse offices.

“I want to emphasize how long I’ve been doing this,” says Mr. Carlson-Wee, who turned 29 last month. “This is really just like breathing in and out for me.”

This account of the windfall and subsequent struggles of Polychain and Mr. Carlson-Wee is based on multiple interviews with people close to the firm, as well as audits and other investor documents reviewed by the Journal.

Mr. Carlson-Wee’s path to high-stakes investing began in Minnesota, in the suburbs of Fargo, N.D., where his parents were Lutheran pastors. In high school, Mr. Carlson-Wee wrote an SAT tutoring program in his spare time. He said he had few friends; his classmates voted him “most unique.”

At Vassar College, he majored in sociology and against advice from his professors wrote a senior thesis on a virtually unknown digital currency named bitcoin.

Bitcoin is software that allows people to exchange value directly, without any government intermediary, essentially functioning as a digital form of money. It was created in 2008 by a person or people under the pseudonym Satoshi Nakamoto.

After graduation in 2012, Mr. Carlson-Wee became the first employee at Coinbase, a nascent cryptocurrency exchange. Until the morning of the interview, he owned only one pair of pants: jeans covered in sap from a short stint as a lumberjack. A shoestring acted as the belt. His $50,000 starting salary was paid in bitcoin.

In July 2016, Mr. Carlson-Wee quit to start one of the first-ever crypto funds out of an apartment he shared with seven roommates in San Francisco’s gritty Mission district.

With a mullet, a wide collection of vintage windbreakers and a tendency to speak extemporaneously on esoteric topics, Mr. Carlson-Wee reminded some investors of the 1980s “Back to the Future” character Marty McFly.

The pitch worked: In December 2016, Union Square Ventures agreed to invest in the fledgling firm at a $5 million valuation, a steep price considering its total assets under management were roughly the same.

Venture capitalist Ramtin Naimi took a stake in Polychain at the same time, and afterward took Mr. Carlson-Wee out to lunch. Over avocado toast, he asked the manager how large Polychain could grow.

“Fifty million dollars is a great target,” Mr. Carlson-Wee responded. A few months later, Mr. Naimi repeated the same question. “I think $400 million is really the right number,” Mr. Carlson-Wee said.

Polychain was growing fast because cryptocurrency was suddenly mainstream. Hundreds if not thousands of startups were forming to use the blockchain, the software that underpins bitcoin. The blockchain is said to be able to help airlines track flights, banks settle accounts and grocers stock food, among other uses.

New, competing cryptocurrencies popped up rapidly via so-called initial coin offerings that could raise hundreds of millions of dollars instantly. The creators of some coins gave them away to Polychain, Mr. Carlson-Wee and other early adopters, hoping for the imprimatur of approval. Polychain would later sell some for profit.

Mr. Carlson-Wee spent hours each day at his computer, occasionally responding to strangers on social-media sites like Reddit, encouraging them to buy bitcoin and the like. More big names in Silicon Valley were beginning to invest in the fund including Sequoia Capital, Bain Capital Ventures and Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, all eager to get access and insight into the crypto phenomenon.

Around the summer of 2017, Polychain irked some of its earliest investors, including friends who had invested months earlier on little more than faith, when it demanded they each invest hundreds of thousands of dollars more. Some didn’t have the cash, and were forced out. Mr. Carlson-Wee says the move was required as Polychain made changes to accommodate larger investors, and that only a small number of Polychain backers were affected.

Mr. Carlson-Wee was growing wary of onetime allies. He raged against an early backer, San Francisco firm Pantera Capital, which started a competing crypto fund while it still had access to Polychain’s trading information. Mr. Carlson-Wee blocked Pantera from receiving updates on Polychain and threatened to force them and other early investors to sell their stakes, before backing down under promise of a prolonged legal fight.

In a statement, Pantera said it “denies that it misused any confidential Polychain information or otherwise violated any obligation to Polychain.”

In early November, Mr. Carlson-Wee paid for around a dozen employees to fly to an oceanfront resort in Cancún. The crypto market was soaring and everyone was relaxed, say attendees; one afternoon, some in the group skipped an iPhone back-and-forth across the pool as they debated whether the device was waterproof. A few minutes later, the phone sank and was ruined.

Mr. Carlson-Wee blames a friend, Richard Craib, for the broken phone.

Mr. Craib, one of the friends who first invested with Polychain, was among those having second thoughts. He had invented his own coin, dubbed the Numeraire, which briefly made him wealthy on paper as investors including Polychain bid it up. But Polychain subsequently sold some Numeraire, depressing the value of Mr. Craib’s holdings. Mr. Craib shortly after redeemed his investment in Polychain funds, for what he says were unrelated reasons.

Union Square, one of Polychain’s earliest backers, was also debating its investment. Polychain was racking up millions in gains, but only on paper, and the digital currency was volatile.

At a panel discussion during Union Square’s annual investor meeting in November, one attendee asked for the firm’s thoughts on Polychain. “Oh, Olaf,” responded Union Square partner Albert Wenger, inserting an extended pause, according to an attendee. “He’s a bit of a gunslinger.”

Union Square co-founder Fred Wilson says he doesn’t recall Mr. Wenger making such a comment and says the firm still has faith in Polychain. Still, Union Square decided to pull some of its money in Polychain late last year, he says, in an effort to “de-risk the investment.” He says Mr. Carlson-Wee is “a quirky guy” who “makes up his own mind and figures things out in his own head.”

Mr. Carlson-Wee isn’t bothered by bitcoin’s daily churns. On a recent weekday afternoon, he left his cellphone in his dusty, black Cadillac Escalade for a 90-minute, technology-free hike to the site of an ancient volcanic crater in the Oakland, Calif., hills.

In between digressions on movie trailers (he won’t watch them, fearing spoilers) and capitalism (in a natural, but not imminent, decline), he talked about how he doesn’t consider himself a trader.

“One thing I want to emphasize is that as a trader, when something doubles, you sell half—or something like that,” he says, making air quotes over the word “trader.” At Polychain, he says, “We don’t trade. We shift around positions.”

Mr. Carlson-Wee describes his approach instead as “long-term, thesis-driven investing.” This philosophy, shared by blue-chip technology investors such as Andreessen Horowitz, is that cryptocurrency is only one branch of a larger upending of the digital world. Most existing online entities, from dating applications to enterprise cloud computing, will be replaced on a less-expensive, decentralized infrastructure, the blockchain.

The question for evangelists is which of the hundreds of competing blockchain platforms will reach widespread adoption. Last year, Mr. Carlson-Wee was largely placing a bet that his favored platform, Ethereum, would win out; more than one-quarter of Polychain’s main fund was invested in Ethereum, according to its most recent audit.

Ethereum is down 74% this year, and Polychain’s main portfolio is down by about 31% through the end of July, the latest figures available. In communications this year with investors, the firm defended its performance as better than the crypto market at large.

Investors in the fund credit a shift from assets such as Ethereum into less-liquid, more stable stakes in crypto companies internationally. That’s a less-volatile bet but one that’s harder to get out of in the case of an extended decline.

Since the start of the year, Polychain has blocked investors from redeeming their money immediately, instead putting investments into a so-called side pocket that now comprises more than half the fund. That means investors can’t cash out fully even if they want to.

“If cryptocurrencies go to zero, we go to zero,” Mr. Carson-Wee said. “I don’t think anyone is under any illusions that’s not the case.”

Mr. Carlson-Wee is rich either way. Unlike many firms that hold illiquid assets that are paid only when they sell investments, Polychain’s main fund takes its fees every year on paper gains. Mr. Carlson-Wee started last year with just $14,502 in the fund, and turned that into $150 million of fees. He cashed out $60 million, a move that raised concerns among investors about his commitment to his own fund.

He says he set aside money for family, and subsequently invested more in the firm’s funds.

“This model will not last,” says Jing Sun, a Polychain investor. Polychain is now raising new funds that won’t charge fees until they realize gains.

Mr. Carlson-Wee and Polychain face a lawsuit filed in March from an early investor, professional poker player Harry Greenhouse. In court filings, Mr. Greenhouse says he asked for his money back late last year and was partly repaid “at cost,” or for the price originally paid, as opposed to what it could be sold for. He alleges Polychain won’t detail how they valued his investment, and suspects he was underpaid.

The matter is in arbitration.

Mr. Carlson-Wee now straddles the line between crypto kid and crypto king. He has pared back his time on online message boards to 15 minutes a day, from an hour or more in years’ past, to spend more time on the fund. He recently chopped off his mullet because being known for such an idiosyncrasy reminded him of “something a hedge-fund manager would do.”

He moved the firm to new offices in a converted warehouse. The San Francisco address listed on Polychain’s public filings is a fake, designed to fool would-be hackers and kidnappers who have targeted other crypto traders.

“This is going to be such an epic adventure either way,” Mr. Carlson-Wee said, smiling. “Like, if this whole thing collapsed, that would be crazy, you know?”

Mastercard, Visa Agree to Settle Merchant Antitrust Suit

The proposed amount of $6.2 billion settles a long-running class-action lawsuit with retailers over the fees they pay when accepting card payments.

Mastercard Inc., Visa Inc. and other financial institutions have agreed to settle a long-running antitrust lawsuit with merchants over the fees they pay when they accept card payments for a proposed settlement amount of about $6.2 billion.

The proposed amount includes $900 million from all of the defendants, including a number of banks that issue debit and credit cards, including JPMorgan Chase Co., Citigroup Inc., and Bank of America Corp. It also includes roughly $5.3 billion already paid by the defendants as part of a $7.25 billion settlement reached in 2012.

Visa’s share of the new settlement is $600 million, which it said it set aside for the settlement on June 28. Including the 2012 settlement money, Visa’s share is $4.1 billion.

Mastercard has agreed to pay an additional $108 million on top of the $790 million it had agreed to pay in a settlement in 2012.

The merchants also allege that the card networks have intentionally set fees and card acceptance rules that primarily benefit the banks. The merchants argue that they want the ability to negotiate their own fees directly with the banks instead of through card networks like Visa and Mastercard, which settle the fees with the banks independently.

The defendants involved in the case said that part of the suit that seeks to revise network rules isn’t covered by Tuesday’s settlement and won’t result in any immediate action while the parties engage in negotiations.

The settlement Tuesday, which was originally reported by The Wall Street Journal in June, would still be subject to court approval.

This could cap a long-running class-action lawsuit that was brought by merchants in 2005 against Visa, Mastercard and the largest U.S. card-issuing banks.

When the original $7.25 billion settlement was reached in 2012, many large merchants opted out largely due to terms that would have barred them from filing lawsuits against the networks over future swipe-fee increases. An appeals court invalidated that settlement on the grounds that merchants weren’t adequately represented. The Supreme Court last year declined to hear the case, shifting it back to the district court.

In this case as well, Mastercard and Visa said they expect to be relieved of all future monetary claims alleged by the class-action suit related to the company’s interchange and fee structure, as well as merchant acceptance rules for at least a period of five years after resolution of appeals.

The card networks have come under scrutiny in particular over the fees they charge merchants when a consumer swipes a card, known as interchange fees, after each transaction. The card networks set the fee and the merchants pay the banks. Yet the merchants in the suit allege that the networks and banks have colluded to inflate those fees.

Investors In Polychain Capital’s Crypto Hedge Fund Saw 1,332% Gains – If They Stomached The Dips

An investor document obtained by CoinDesk charts the dramatic ups and downs of the first four years of Polychain Capital’s cryptocurrency hedge fund, offering an exhaustive look at the performance of one of the sector’s top investment firms.

Yearly returns jumped from a 2.7 percent loss in 2016 to a 2,278.8 percent gain in 2017, according to the document, which accounted for returns up to November of last year. They then nosedived for a 60.4 percent loss in 2018, and surged to a 56.1 percent gain in 2019.

The roller-coaster changes are emblematic of the wild swings familiar to crypto investors small and large. At the same time, the hedge fund’s performance altogether flies in the face of common wisdom and regular markets. Investors who kept money over the hedge fund’s lifetime would have netted 1,332.3 percent, according to the document, raising the possibility that a longer outlook may offset incremental risks.

According to the Bloomberg All Hedge Fund Index, non-cryptocurrency hedge funds overall returned losses of 5.9 percent in 2018 and respective gains of 4.0 percent, 9.2 percent and 9.0 percent in 2016, 2017 and 2019. As a benchmark, leading hedge funds not belonging to the cryptocurrency space gain 15 percent to 35 percent over their lifetimes.

Polychain Capital declined to comment. Whether returns are realized depends on when Polychain Capital’s investors – which include distinguished venture capital firms Andreessen-Horowitz, Founders Fund, Sequoia Capital and Union Square Ventures – deposit and withdraw their funds.

Polychain Capital’s hedge fund lock-up period is at least six months, a time horizon that yields wildly conflicting snapshots due to monthly volatility and spells danger for short-term investors who run on lower liquidity.

In a tabulation of 39 months of activity beginning in September 2016, the hedge fund’s return curve climbed higher for one of four months in 2016, 10 of 12 months in 2017, three of 12 months in 2018 and six of 11 months in 2019. While 20 months saw gains, 19 months saw downturns.

On average, returns dropped 3.3 percent on a monthly basis, according to the document. Negatively moving months were clustered in the last quarter of every year, and appeared in the first two quarters of 2018 and 2019.

The best six-month stretch gained 529.5 percent from January to June 2017, compared to 47.6 percent lost in the worst six-month run from July to December 2018, by CoinDesk’s calculations.

Token Deals

Matt Perona, Polychain Capital’s COO and CFO, is the former chief financial officer of Criterion Capital, a shuttered equity hedge fund that owned deprecated social media site Bebo. Ex-Tiger Legatus hedge fund COO Joe Eagan is Polychain Capital’s president.

Olaf Carlson-Wee, Polychain Capital’s chief investment officer, founded the cryptocurrency investment firm in 2016. The hedge fund is Polychain Capital’s first fund and invests in parallel with a venture capital arm.

Polychain Capital started raising $200 million for a second venture fund this year. March 2019 filings with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) reported $595.1 million in aggregate Polychain Capital holdings, including $175 million raised for the first venture fund in 2018.

According to an accompanying investor deck, more than 20 cryptocurrency assets average $20 million positions each out of the $550 million in assets the hedge fund says it controlled in the fourth quarter last year.

Half of the crypto assets are liquid coins trading on cryptocurrency exchanges, the deck says, and half are illiquid coins that were sold through digital token sales structured under a Simple Agreement for Future Tokens (SAFT).

A SAFT is an investment contract that stipulates that a digital token is a security and freezes redemption until the token technology – ordinarily a blockchain network or a computing protocol – becomes usable.

Though viewed as a regulatory concession by investors and token issuers, a SAFT is not officially recognized as a valid legal framework by the SEC, the government agency that authorizes offerings of securities.

Updated: 8-17-2020

Pantera Tells SEC Its Crypto Fund Has Raised Nearly $165M

Institutions and the well-heeled have poured millions of dollars into a Pantera Capital fund, helping it more than double in size since it launched in 2018.

* The Pantera Venture Fund III has received $164.7 million in private placements from just under 200 investors, according to a Form D filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Friday.

* That’s nearly $60 million more than at the date of its last filing in 2019 and well over $93 million – double – what the fund had two years from when it first filed with the U.S. markets watchdog.

* Pantera declined to disclose the fund’s revenue.

* A Form D exempts offerings directed at accredited investors from registering with the SEC

* Asset manager New York Digital Investments Group (NYDIG) has used this exemption for the three crypto funds it has launched just this year.

* But Pantera’s filing, this year’s as well as in previous years, has claimed a 3(c)7 exemption, meaning its offering is aimed at the higher-tiered qualified purchasers, or those with at least $5 million in investments.

* Pantera had originally hoped to raise $175 million for Venture Fund III and said in March last year it had crossed the $160 million milestone.

* Per a blog post, Pantera disclosed it had primarily invested in infrastructure, finance and exchanges in the digital asset space.

* One of its first investments was the institutional derivatives exchange Bakkt.

Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,vOlaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,vOlaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,vOlaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,vOlaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,vOlaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,vOlaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,vOlaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,Olaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,vOlaf Carlson-Wee Rode The,

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.