Where The Best Paying Jobs Are (#GotBitcoin)

To determine the overall hottest and coldest labor markets, We looked at the 53 metro areas with more than 1 million people. Where The Paying Best Jobs Are (#GotBitcoin)

Updated: 8-9-2021

Corporate America Is Ponying Up For Workers Suddenly In Demand

For the first time in decades, the American worker is finally in command when it comes time to talk money.

There are tell-tale signs everywhere that this is so.

Like the way some employers — such as Kroger Co., Chipotle Mexican Grill Inc. and Under Armour Inc. — are frantically pushing up hourly wages to try to retain employees. Or the way others — like Starbucks Corp. and Drury Hotels — are dangling hiring bonuses to entry-level applicants. Or the way CVS Health Corp. is no longer requiring job seekers to have high-school diplomas. Or the way Dan Sacco, the owner of Your Pie restaurants in Iowa, is instructing his general managers to poach workers from rivals with offers of better hours and higher pay.

Related:

We Look At Who’s Hiring vs Who’s Firing (#GotBitcoin)

The Inside Scoop On The Booming Crypto Job Market

With Crypto Jobs Available, US Universities Are Turning to Blockchain Education (#GotBitcoin?)

This Sector Could Have A Half Million Job Openings And Opportunities For Older Workers

Coronavirus Commercial And Residential Cleaning Services See A 75% Spike In Demand

Workers Are Quitting Hotel And Restaurant Jobs At The Highest Rate On Record

Helping 10,000 People Get A Job In Crypto

To Survive The Pandemic, Entrepreneurs Might Try Learning From Nature

“Everything is fair game now,” Sacco says.

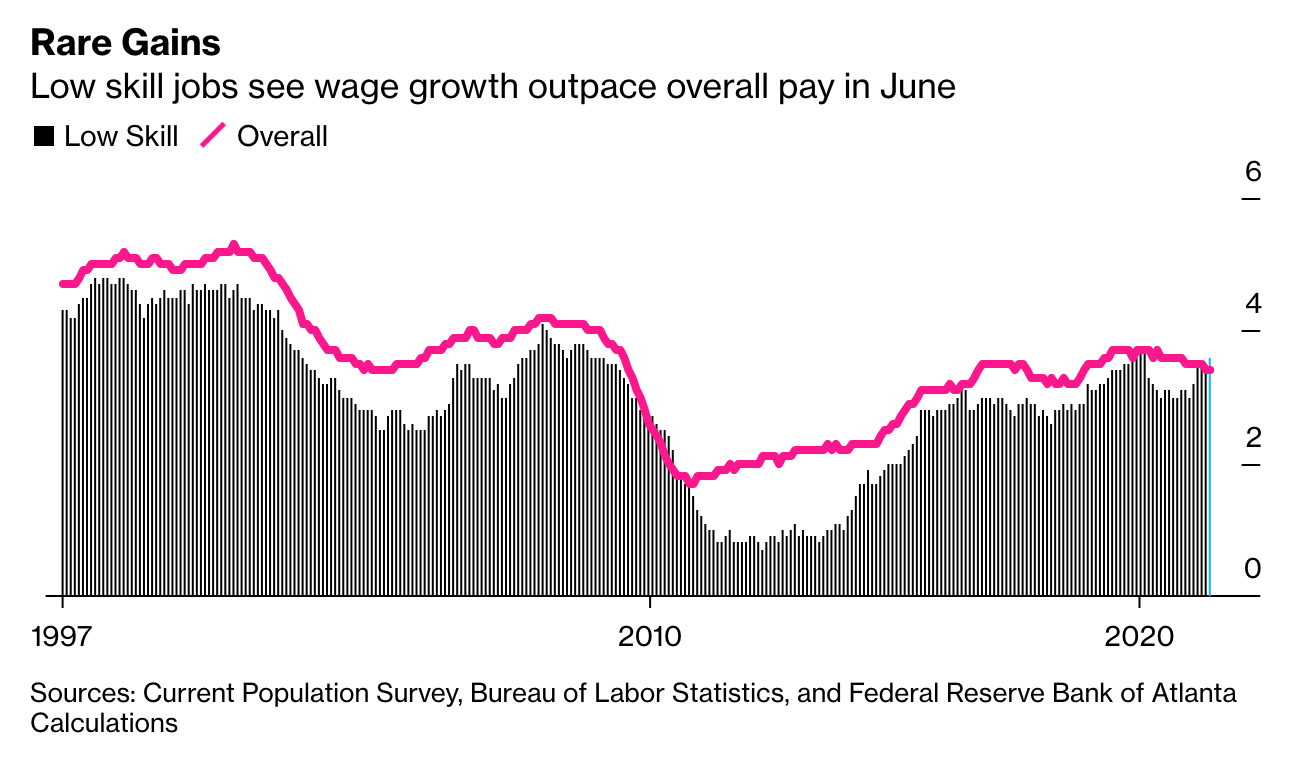

It is unclear how long all of this will last in the wild and disjointed economic recovery that’s followed last year’s pandemic collapse. But one thing is certain: Workers are scoring the fattest pay hikes since the early 1980s.

Wages for the leisure and hospitality industry have surged at an annualized pace of 6.6% over the past two years. And data released Friday showed that payrolls rose nationally at the fastest pace in almost a year, a sign of how desperate employers are to fill jobs.

“If you’re not able to get staff to cover, it leaves you really crunched and that’s what we’re seeing at the moment,” said Neil Saunders, a managing director at market research firm GlobalData who covers retailers and grocers. “Wages have gone up and have been going up.”

There’s a risk the party could peter out as the delta variant causes U.S. coronavirus infections and hospitalizations to pick up, mostly among the unvaccinated. Some events, like the New York International Auto Show, are being canceled due to virus concerns. Companies including Alphabet Inc.’s Google, Amazon.com Inc. and BlackRock Inc. have all recently pushed back plans to return to the office as well. Economists at Bank of America Corp. have reported slowing momentum in credit-card spending.

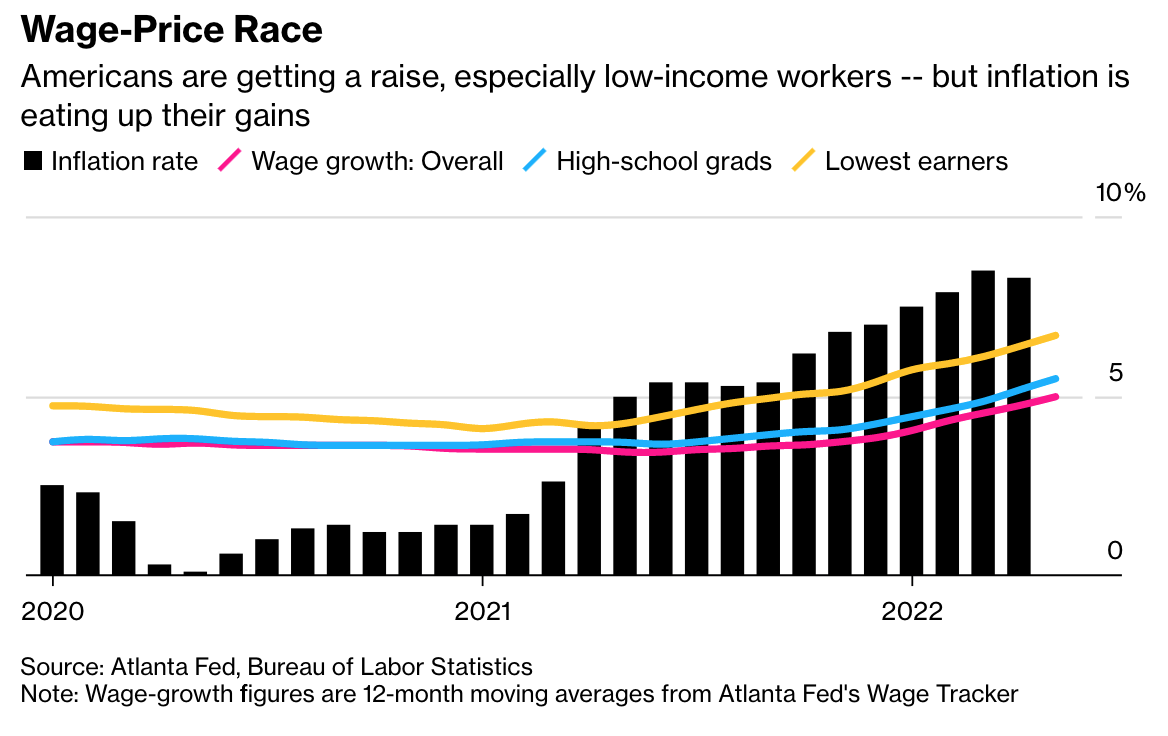

Inflation is another complicating factor that’s limiting the benefits of pay raises. Consumer prices surged 5.4% in June from a year ago, the fastest pace since 2008. According to a Peterson Institute study, inflation-adjusted compensation for all civilian workers is now lower than it was in December 2019.

But if policy makers can tamp down on the price increases, workers should do well. Data from the Labor Department show median wage growth was 4.8% in July on a 24-month annualized basis, up from a 3.3% pace in January 2020. Service workers saw gains almost two percentage points higher than the average for all employees last month.

That could help narrow income inequality, however slightly, after years of widening gaps amid fairly stagnant wages for the service industry accompanied by soaring salaries for white-collar workers. For the most part, corporate America expects wage increases to continue.

The subject came up at a recent meeting with Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen in Atlanta, where she gathered senior leaders from companies including Delta Air Lines Inc. and Coca-Cola Co. to talk about inflation and the economy.

During private discussions, some executives bemoaned the fact they still can’t fill open positions even after wages were increased, according to a person familiar with the conversation. The consensus among employers was that higher pay is here to stay.

A Starbucks location in Manhattan is offering a $200 signing bonus to anyone who joins by the end of the month. Kroger said by the end of the year the average hourly rate at its grocery stores will be about $21, when comprehensive benefits are considered, up from $15.50 in March. And recruiting efforts have spread far and wide, with Church’s Chicken passing out coupon books that say “Always Hiring.”

At Amazon, warehouse workers and other hourly employees got raises this year as the retailer seeks to retain talent. Amazon is spending heavily on signing incentives, Chief Financial Officer Brian Olsavsky said during a call with analysts last month.

“It’s a very competitive labor market,” Olsavsky said.

Darius Adamczyk, the CEO of Honeywell International Inc., is doling out wage hikes of more than 10% for some factory workers. He’s trying to raise prices to offset steeper costs for labor, materials and services. Those higher wages will probably stick, since companies rarely reverse increased pay rates.

“If labor costs go up permanently, then we’re going to have to figure out how we sustain at least some level of that pricing power,” Adamczyk said in an interview.

In Iowa, Sacco says his Your Pie pizzerias have been able to hire a few more people after offering higher wages. He pays about $10.50 an hour, and workers often earn another $2 an hour in tips. His other recruiting pitch is a better schedule. He’s poached a few workers from nearby rivals that are open until 1 a.m., later than his restaurants’ 9:30 p.m. closing time.

There are some businesses who say the tide is turning in their favor. McDonald’s Corp. CEO Chris Kempczinski said after raising wages about 5% in its U.S. locations, applications have increased significantly, particularly as the federal stimulus has ended in parts of the country. Critics have argued that workers have stayed on the sidelines because of cash transfers and unemployment benefits.

Noodles & Co., a fast-casual restaurant chain, saw a 70% jump in applications in June compared with April.

“We’re starting to see the light at the end of the tunnel in terms of the whole staffing shortage,” CEO Dave Boennighausen said.

Labor Secretary Marty Walsh says the U.S. job market is healthy as people resume traveling and eating out at restaurants, though he acknowledged that delta variant poses a risk. Vaccinations and wage growth are encouraging people to return to the workforce, though salaries may have to go higher, he said in an interview Aug. 6 after the payrolls report.

“Wage growth is good. It’s good for the American worker,” Walsh told Bloomberg Television. “In some sectors, we’re definitely going to need to see higher wage growth for people to come back to work. But I think where we’re headed right now, all signs are incrementally going in a good, positive direction.”

Updated: 3-1-2019

A Look At The 10 Hottest And Coldest Labor Markets In The U.S.

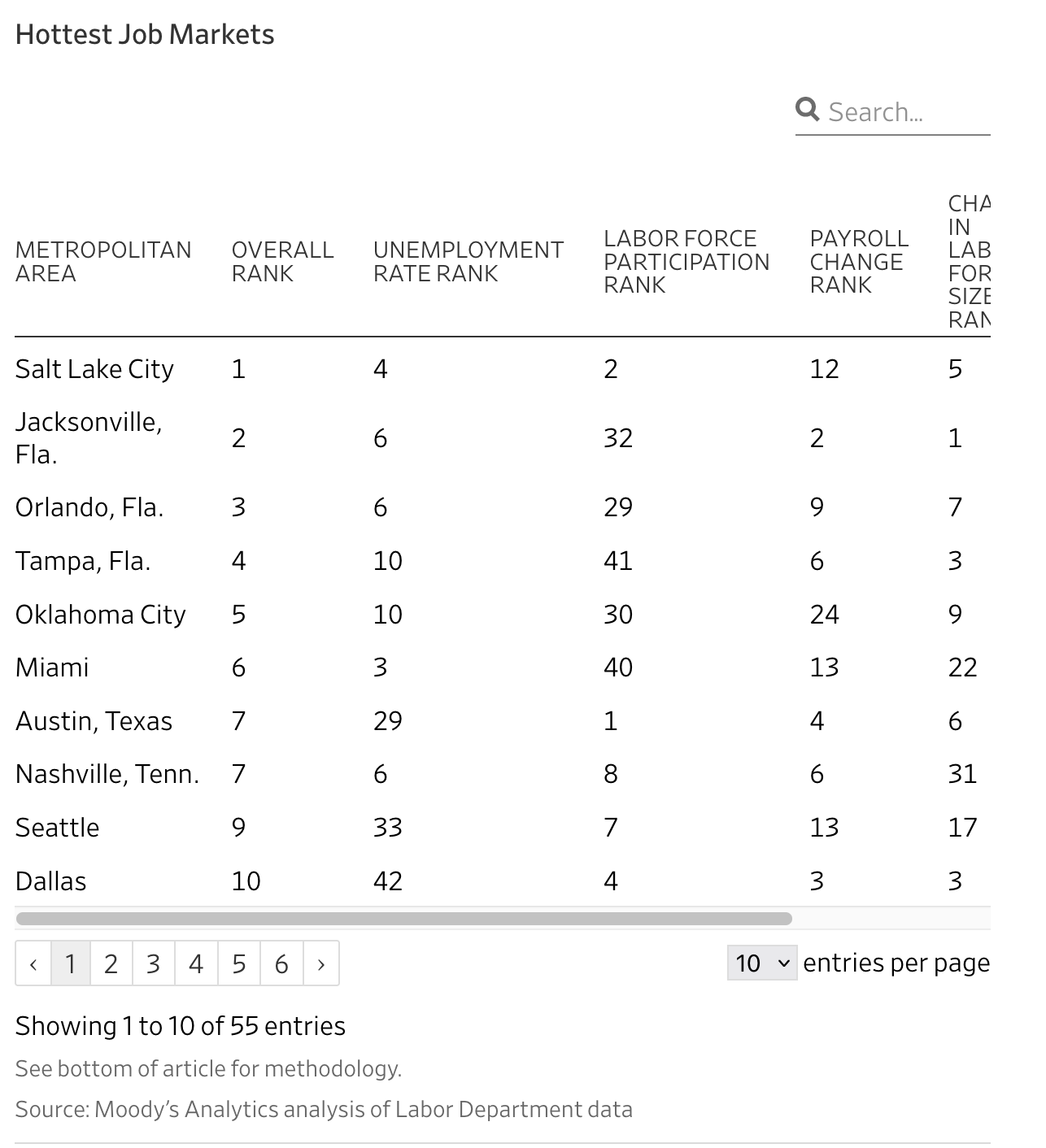

The ranking is based on five attributes: average unemployment rate in 2018; labor-force participation rate in 2018; the change in employment and change in labor force for the fourth quarter of 2018 from a year earlier; and the change in average weekly wage in the first half of 2018 from the first half 2017, reflecting the latest available wage data. The area with the highest average ranking among the five categories was determined to be the hottest labor market. Moody’s Analytics provided the analysis of Labor Department data necessary for this report.

In This Oil Boom Town, Even a Barber Can Make $180,000

One of America’s hottest labor markets is in West Texas, where the brisket is scarce, the ‘man-camps’ are full, and oil workers with no time to spare pay $75 to skip the line at the barber shop.

West Texas has seen its share of oil booms, but the people there say this one is unlike any they’ve seen.

Driven by shale drilling, a gusher of crude production has transformed the Permian Basin into America’s hottest oilfield, turning what was a remote stretch of towns spread among mesquite trees and scrubland into an industrial zone, seemingly overnight.

Fortunes are being made in this fracking-related gold rush, and money and workers are flooding in. But many necessities in the area now cost a small fortune, creating opportunities for businesses selling everything from dipping tobacco to sand for fracking. It can be hard to get a haircut, grab a plate of good Texas barbecue, or find a table at a popular bar, because demand outstrips supply. Housing is scarce and hotel room prices sometimes rival those of New York City at more than $500 a night.

There are more than 300 metropolitan areas across the U.S. with fewer than 1 million people. The Midland-Odessa job market, in the heart of the fracking boom, was the hottest of all of them last year, according to our analysis. Among those metro areas, Midland had the fastest job and labor-force growth, and one of the lowest unemployment rates, a monthly average of 2.3% in 2018.

Oil prices have fallen about 25% since October to around $57 a barrel. But West Texas residents are hopeful the boom won’t go bust soon because companies have pumped billions into building out the oilfield, and drilling is not expected to peak for years.

The Permian produced an average of more than 3.9 million barrels per day as of January, according to the Energy Information Administration. Analytics firm IHS Markit estimates Permian production could top 5 million barrels a day in 2023, surpassing Iraq.

Here’s What A Modern-Day Boomtown Looks Like.

$180,000 For A Barber

Pete McGarity opened Headlines Barber Shop in Odessa in 1998 and has ridden the boom-bust cycle before. This time around he decided to capitalize on it.

In 2017, Mr. McGarity spent about $25,000 to retrofit a trailer into a custom, mobile barber shop. That October, he drove it about an hour west to Pecos, Texas, and parked in front of the town’s only grocery store, hoping to catch oil field workers between shifts. It was an instant success.

“It was crazy, it went berserk,” says Mr. McGarity, 48. “I’d show up around one o’clock and we’d cut until after midnight.”

These days Mr. McGarity sends the trailer to Pecos, which is closer to the oilfields, six days a week with five barbers, who cut hair all day long. A cut costs as much as $40, more than the $25 he charged before the boom. There is usually a long waiting list, but patrons can cut the line if they pay $60, or $75 with a shave, a popular option with oil workers.

“It is flooded with oilfield workers galore, and these guys tip well,” he says.

Mr. McGarity’s barbers are raking it in. Those who venture to Pecos can make anywhere from $130,000 to $180,000 per year, he said. He is considering investing in additional trailers to send to farther-flung towns in the oil patch and says the additional revenue may allow him to retire soon. If there’s a bust, he’ll just store the mobile shops until things come back, he adds.

By The Numbers: Headlines Barber Shop

$30 To $40 For A Haircut

$60 To Cut The Line

About 20 Haircuts Given Daily By Each Barber

$700 To $900 Made Daily By Each Barber

Brisket Shortage

If you’re hoping to get some brisket at Pody’s BBQ in Pecos, you’d better show up early. During the week, there are usually 30 or more oil field workers lined up outside the restaurant before it opens at 11 a.m., an unusual sight for the small town before the boom.

Israel Campos says he has doubled his sales since starting the restaurant in 2012. Mr. Campos, 44 years old, says he is lucky his staff is family members, because many restaurants in the area struggle to keep workers, who are lured away by higher paying oil industry jobs.

The oil hands waiting in line will often order for their co-workers, sometimes 10 plates at a time, according to Mr. Campos. Company men frequently call ahead with larger orders they bring to drilling rigs or even fly out on private planes, he says.

“We sell out daily and we hardly see any locals because the oil field comes and buys us out,” Mr. Campos says. “Locals tell me ‘I won’t even attempt to come to your place,’ and I’m like, ‘sorry dude.’”

Mr. Campos grew up in Pecos, whose population neared 10,000 in 2017, according to the Census. He was recently elected Reeves County commissioner and says that if a bust comes, it just means locals will be able to eat at the restaurant again.

By The Numbers: A Typical Day At Pody’s

25 Briskets (Up From 6 In 2012), Or About 250 Pounds Of Meat

20 Racks Of Pork Spare Ribs, Or About 60 Pounds Of Meat

150 Pounds Of Sausage

50 Pounds Pulled Pork

Boom Town, U.S.A.

A gusher of crude production has transformed the Permian Basin into America’s hottest oilfield, turning what was a remote corner of the country into a prosperous boom town, seemingly overnight.

No Seats At The Bar

When oil field workers want to blow off steam, many head to one of the most popular bars in Odessa, The Shack in the Back. Bar owner April Williams says patrons appreciate the Shack’s laid-back atmosphere and outdoor patio centered on a stretch of grass, uncommon in the area.

It’s so popular that oil companies pay $6,000 or more for tables while the bar is in season, about seven months a year. The bar is only open Wednesday nights, and is otherwise closed for weddings or corporate parties, so the fee works out to around 28 nights. Companies get a guaranteed picnic table on the patio and some employees and guests don’t have to pay the $10 cover. Reserving a table for just one evening costs as much as $100.

The tables are already booked for next season, says Ms. Williams, who opened the bar 15 years ago. It gets slower when oil prices are down, she adds, but she’s not that worried about a bust.

“People drink when they’re happy and people drink when they’re depressed,” she says.

By The Numbers: A Typical Wednesday At The Shack

800 Patrons

125 Cases Of Beer

60 Tables Reserved For One Night For Around $100

25 Tables Reserved For The Season

Townhouses For Teachers

The frenzy of money and workers has downsides. Chief among them is a paucity of affordable housing. There’s such a shortage that school districts in the Permian basin are considering building rental homes for teachers as rising housing costs make it increasingly difficult to recruit, even as public school enrollment in the Midland region has jumped 9% in five years, according to the Texas Education Agency.

The median home value in Midland, Texas was $256,600 as of January, according to Zillow Group Inc., up about 30% since oil dipped below $30 a barrel in 2016. Meanwhile, oil and gas workers earning top dollar have scooped up much of the available rental housing.

In Fort Stockton, about two hours southwest of Midland, the boom has exacerbated the already difficult problem of finding teachers willing to move out to the remote town of about 8,000, where new hires stand to earn $42,500. In response, the local school district is looking to build at least six duplexes to rent to teachers. The district already owns land where the homes could be located.

“If we have some keys we can dangle in front of them, it takes one thing off their plate if someone’s trying to move,” says Ralph Traynham, superintendent of the Fort Stockton Independent School District. The project is expected to cost about $2.8 million, Mr. Traynham said.

Not Your Father’s Man Camp

Chief Executive Brad Archer says Target’s facilities, which it calls lodges or communities, are vastly upgraded from the man-camps of years past. They include weight rooms, memory foam mattresses, executive chefs and even swimming pools.

“It’s definitely not my dad or your dad’s oil field,” Mr. Archer says.

Many oil workers live in temporary housing complexes, known as man-camps. Such camps have been a mainstay of oil booms over the last decade, offering frequently spartan, dormitory-like housing for influxes of temporary workers.

But as the man-camp game has become more competitive, some have become more upscale in a bid to win business. Target Lodging is the largest operator of man camps in the Permian basin. It’s invested hundreds of millions in the region and has gone from 80 beds in 2012 to 8,500 beds currently.

Mr. Archer says that the influx of workers to the region, some of whom can make six figures, are requiring creature comforts one wouldn’t typically associate with the oil patch. Target’s customers are oil companies who sign up for long-term contracts to house their workers. The company declined to disclose its rates, but analysts say higher-end man camps can charge $1,500 to $3,000 per month, depending on food and other services included.

Target offers rotating menus from chefs Mr. Archer says have worked in top tier restaurants around the world. At the lodge in Pecos, a worker can eat salmon and fresh vegetables in the dining hall or order wood-oven pizza and watch a football game at the “Frac Shack,” a sort-of sports bar, sans alcohol.

By The Numbers: Food Served By Target In The Permian In 2017

86,525 Pounds Of Bacon

16,200 Pounds Of Potatoes For Hand-Cut French Fries

76,500 Pounds Of Ground Beef

1.8 Million Eggs

32,200 Cases Of Oranges For Freshly Squeezed Orange Juice

26,000 Gallons Of Milk

2.3 Million Bottles Of Water

How To Make The Booming Job Market Work For You

Is Now The Time To Change Jobs, Push For That Raise Or Lobby For A New Assignment?

The job market a decade ago was in such free fall that multiple generations are still feeling the scars of lost income and thwarted career opportunities. By contrast, the demand for workers now is so hot, it’s easy for many job seekers–especially those with sought-after tech skills–to feel almost giddy.

Rule No. 1 Of Today’s Booming Labor Market Remains The Same As Before: Don’t Overplay Your Hand.

Sure, employers need more people. Yes, many are even offering to train recruits on the job. But threatening to bolt if your boss won’t grant you a $10,000 raise? That still isn’t likely a winning strategy.

You can make a hot job market work for you, though—whether you aim to change companies or stay put. A guide to making the most of it now:

Don’t: Be Flattered Into Swapping Jobs

In a labor market this strong, it can be tempting to switch employers, especially when more money is on the table. But money shouldn’t be the sole consideration or even, perhaps, the biggest one. Rather, one of the best reasons to leave a role is when it doesn’t offer the right challenge–or a sense of control, says Daniel H. Pink, author of “When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing.” A job with a relentless schedule, and few inspiring problems can lead to burnout.

Do: Create A Career Map

Before swapping jobs, consider how a move may steer your career. Dawn Fay, senior district president at staffing firm Robert Half, recommends a career inventory, assessing where you want to go. Some job switchers also swear by elaborate spreadsheets, listing every pro and con of a potential move, from commuting time to growth opportunities. “It’s really, really critical for people to be well thought out about why they’re making a change,” Ms. Fay says. “You never want to change jobs just because everyone else is changing jobs.”

Do: Let Your Current Employer ‘Re-Recruit’ You

Companies don’t want to lose good employees, particularly at this moment, when it may be tougher to replace them. So many are “re-recruiting” workers, finding ways to make roles more attractive by changing responsibilities or offering development opportunities, Ms. Fay says. Brainstorm what your current employer can offer, she says; now may be an opportune time to speak up about an internal assignment you’ve coveted.”

Do: Get Creative In Asking For Benefits

More organizations are now offering student-loan repayment and money for educational expenses. Look for other areas to negotiate, too, says leadership consultant Roberta Matuson. Some of her clients now ask to be reimbursed for work with an executive coach, particularly if they’re entering a stretch role. She also advises workers to negotiate for extra vacation—“discretionary time is really the measurement of wealth,” she says—along with greater flexibility. And if a different title may prove helpful, ask for it. Finally, get everything in writing, Ms. Matuson says; your current boss could also head elsewhere soon.

Don’t: Ask For A Raise Unless You Can Show Results.

A tight labor market alone likely won’t convince your boss to fork over more cash. You’ll still need a strategy to clinch a raise, says Donna Morris, chief human-resources officer at software maker Adobe . Start by focusing on your own performance, delivering unquestionably good results, she advises. A discussion with your boss is also in order. She recommends asking: “If I want the top raise this year, what am I going to have to do?” The conversation should be ongoing, with regular check-ins.

Don’t: Bring Up A Counteroffer Without A Strategy

If you’re going to present your boss with an offer for a higher salary from another company, do so in the context of a broader discussion over your career prospects. Emphasize what you value about your current job, but express concerns about foregoing a higher salary. Don’t bring up a job offer you’re not willing to take. If your employer calls your bluff, know what you plan to do next.

Inside The Hottest Job Market In Half A Century

A look at who’s getting ahead, who could be left behind and how long the boom can last.

The job market doesn’t get much better than this. The U.S. economy has added jobs for 100 consecutive months. Unemployment recently touched its lowest level in 49 years. Workers are so scarce that, in many parts of the country, low-skill jobs are being handed out to pretty much anyone willing to take them—and high-skilled workers are in even shorter supply.

All sorts of people who have previously had trouble landing a job are now finding work. Racial minorities, those with less education and people working in the lowest-paying jobs are getting bigger pay raises and, in many cases, experiencing the lowest unemployment rate ever recorded for their groups. They are joining manufacturing workers, women in their prime working years, Americans with disabilities and those with criminal records, among others, in finding improved job prospects after years of disappointment.

There are still fault lines. Jobs are still scarce for people living in rural areas of the country. Regions that rely on industries like coal mining or textiles are still struggling. And the tight labor market of the moment may be masking some fundamental shifts in the way we work that will hurt the job prospects of many people later on, especially those who lack advanced degrees and skills.

But for now, at least, many U.S. workers are catching up after years of slow growth and underwhelming wage gains.

One face of the red-hot job market is Cassandra Eaton, 23, a high-school graduate who was making $8.25 an hour at a daycare center near Biloxi, Miss., just a few months ago. Now she earns $19.80 an hour as an apprentice at a Huntington Ingalls Industries Inc. shipyard in nearby Pascagoula, where she is learning to weld warships.

The unemployment rate in Mississippi, where Huntington employs 11,500 people, has been below 5% since September 2017. Prior to that month, the rate had never been below 5% on records dating back to the mid-1970s. In other parts of the country, the rate is even lower. In Iowa and New Hampshire, the December jobless rate was 2.4%, tied for the lowest in the country. That’s helped shift power toward job seekers and caused employers to expand their job searches and become more willing to train applicants that don’t meet all qualifications.

“It’s amazing that I’m getting paid almost $20 an hour to learn how to weld,” says Ms. Eaton, the single mother of a young daughter. When she finishes the two-year apprenticeship, her wage will rise to more than $27 per hour.

It’s no surprise to economists that many people who were previously left behind are now able to catch up. It’s something policymakers have been working toward for years. Obama administration economists debated how to sustain an unemployment below 5%. Now Trump administration officials are considering how to pull those not looking for jobs back into the labor force.

“If you can hold unemployment at a low level for a long time there are substantial benefits,” Janet Yellen, the former chairwoman of the Federal Reserve, said in an interview. “Real wage growth will be faster in a tight labor market. So disadvantaged workers gain on the employment and the wage side, and to my mind, that’s clearly a good thing.”

This was one of Ms. Yellen’s hopes when she was running the Fed from 2014 to 2018; keep interest rates low and let the economy run strong enough to keep driving hiring. In the process, the theory went, disadvantaged workers could be drawn from the fringes of the economy. With luck, inflation wouldn’t take off in the process. Her successor, Jerome Powell, has generally followed the strategy, moving cautiously on rates.

“This is a good time to be patient,” Mr. Powell told members of Congress Tuesday.

Looming Risks

The plan seems to be paying big dividends now, but will it yield long-term results for American workers?

Two risks loom. The first is that the low-skill workers who benefit most from a high-pressure job market are often hit hardest when the job market turns south. Consider what happened to high-school dropouts a little more than a decade ago. Their unemployment rate dropped below 6% in 2006 near the end of a historic housing boom, then shot up to more than 15% when the economy crumbled. Many construction, manufacturing and retail jobs disappeared.

The unemployment rate for high-school dropouts fell to 5% last year. In the past year, median weekly wages for the group rose more than 6%, outpacing all other groups. But if the economy turns toward recession, such improvement could again reverse quickly. “The periods of high unemployment are really terrible,” Ms. Yellen said.

The second risk is that this opportune moment in a long business cycle might be masking long-running trends that still disadvantage many workers. A long line of academic research shows that automation and competition from overseas threaten the work of manufacturing workers and others in mid-skill jobs, such as clerical work, that can be replaced by machines or low-cost workers elsewhere.

The number of receptionists in America, at 1.015 million in 2017, was 86,000 less than a decade earlier, according to the Labor Department. Their annual wage, at $29,640, was down 5% when adjusted for inflation.

Tougher trade deals being pushed by the Trump Administration might help to claw some manufacturing jobs back, but economists note that automation has many of the same effects on jobs in manufacturing and the service section as globalization, replacing tasks that tend to be repeated over and over again.

Andrew McAfee, co-director of the MIT Initiative on the Digital Economy, said the next recession could be the moment when businesses deploy artificial intelligence, machine learning and other emerging technologies in new ways that further threaten mid-skill work.

“Recessions are a prime opportunity for companies to reexamine what they’re doing, trim headcount and search for ways to automate,” he said. “The pressure to do that is less when a long, long expansion is going on.”

With these forces in play, many economists predict a barbell job market will take hold, playing to the favor of low- and high-skill workers and still disadvantaging many in the middle.

Reaping Gains

The U.S. is adding jobs in low-skilled services sectors. Four of the six occupations the Labor Department expects to add the most jobs through 2026 require, at most, a high-school diploma. Personal-care aide, a job which pays about $11 an hour to help the elderly and disabled, is projected to add 778,000 jobs in the decade ended in 2026, the most of 819 occupations tracked. The department expects the economy to add more than half million food prep workers and more than a quarter million janitors.

Those low-skill workers are reaping pay gains in part because there aren’t a lot of people eager to fill low-skill jobs anymore. Only about 6% of U.S. workers don’t hold a high school diploma, down from above 40% in the 1960s, according research by MIT economist David Autor.

James O. Wilson dropped out of high school in the 10th grade and started selling drugs, which eventually led to a lengthy incarceration. When Mr. Wilson, 59, was released in 2013 he sought out training at Goodwill, where he learned to drive a forklift. Those skills led him to a part-time job at a FedEx Corp. facility at an Indianapolis, Ind., airport. He was promoted to a full-time job in 2017, and is now earning more than $16 an hour. He has a house with his wife and enjoys taking care of his cars, including a prized Cadillac.

“I wanted to show FedEx you can take a person, and he can change,” he said. “I want FedEx to say, ‘Do you have any more people like him?’”

Skilled workers in high-tech and managerial positions are also benefiting from the high-pressure labor market, particularly in thriving cities. Of 166 sectors that employ at least 100,000 Americans, software publishing pays the highest average wages, $59.81 an hour in the fourth quarter of 2018. Wages in the field grew 5.5% from a year earlier, well outpacing 3.3% overall growth in hourly pay. The average full-time employee in the sector already earns more than $100,000 a year.

More Jobs, More Money

Last year was a good time to be an employee—or become one—in most industries. Nearly three-fourths of 166 sectors the we reviewed saw gains in employment and earnings last year. Only four experienced a drop in both.

Other technical industries, scientific research and computer systems design, were also among the five best paying fields. Some of the hottest labor markets in the U.S.—including Austin, Texas; San Jose, Calif.; and Seattle—have more than twice the concentration of technical jobs as the country on average.

Analysis of Moody’s Analytics data found Austin to be the hottest labor market in the country among large metros. It ranked second in job growth, third for share of adults working and had the sixth-lowest unemployment rate last year, among 53 regions with a population of more than a million. San Jose, the second-hottest labor market, had the lowest average unemployment rate last year and the second-best wage growth.

Missing Out

While a strong economy is conveying benefits to a broad swath of Americans, those in rural areas aren’t experiencing the same lift from the rising tide.

In metro areas with fewer than 100,000 people and in rural America, the average unemployment last year was a half-percentage point higher compared to metro areas with more than a million people, according to analysis by job search site Indeed.com.

“Finding work can be challenging for rural job-seekers because rural workers and employers both have fewer options,” said Indeed economist Jed Kolko. “Many rural areas have slow-growing or shrinking populations.”

Bradley Cox lives in Vevay, Ind., a rural community of fewer than 2,000 people. The 23-year-old graduated with a bachelor’s degree in business administration and liberal arts from Indiana University East in December, but said he had found opportunities limited in his region.

After years working in hourly positions at a casino, he took a job last summer as a cashier at a CVS Health Corp. drug store, making about $12 an hour. He hoped to work at a bank, or perhaps in a traveling sales role, making use of his business degree. “But to be honest, for me to do that, I would have to move to one of the cities or commute to one of the cities, at least,” he says. “I don’t have the opportunity around where I live.”

Other workers are employed—but need to string together two or more jobs to make ends meet.

Michelle Blandy, 48, had a full-time digital marketing job in Phoenix, but hasn’t been able to find steady work since moving to Harrisburg, Pa., to be closer to her family. Instead she’s pieced together some freelance projects, occasionally drives for Lyft and sells refurbished jewelry boxes on Etsy. “I have applied for full-time jobs, I just didn’t have any luck,” she said. “Harrisburg is tiny compared to Phoenix. There’s not as many tech companies or big companies here that are hiring.”

The good news is this long run of low unemployment could last for a while. Economic theory holds that when unemployment is very low, it stirs inflation, which causes the Federal Reserve to raise short-term interest rates and short-circuit growth and hiring. That kind of cycle ended the 1960s period of low unemployment, but inflation in this period remains below the Fed’s target of 2%.

That’s allowed the Fed to keep rates low. By January 1970, when the unemployment rate was 3.9%, the Fed had raised its target short-term interest rate to more than 8% to fight inflation. By contrast, when the jobless rate fell below 4% last year, the Fed kept its target rate below 2.5% thanks to low inflation.

“It may turn out that lower unemployment proves to be more sustainable than it was in the 1960s,” says Ms. Yellen. “I think we don’t know yet.”

Updated: 10-11-2019

Here Are The U.S. Cities With The Highest Growth In Job Openings And Wages

The analysis was carried out by Glassdoor based across major metro areas.

The U.S. job market is still strong, but some cities appear to have more pep than others.

The top three cities for the most job openings are Boston (up 8.4% year over year in September with 152,683 open jobs), Philadelphia (up 6.4% over the same period with 112,692 open jobs) and Atlanta (up 5.5% with 192,889 open jobs), according to Glassdoor’s latest job market report. That compares favorably to an overall growth of 3.5% in job openings annually in September, with total open job openings nearing 6 million.

Government figures provide a deeper dive into actual job growth across 52 major metro areas. Ocean City, N.J. had the largest annual percentage increase in actual job growth (7%) in August, according to the latest data released by the Bureau of Labor Statistics last week, followed by Reno, Nev. (5.5%), and Ogden-Clearfield, Utah (4.6%). Glassdoor’s analysis is based on millions of online jobs and salaries in major metro areas across the U.S. listed on its site.

‘Today’s [jobs] growth is a far cry from the blockbuster job market in 2018. Growth in job openings slowed to 3.5% in September.’

—Glassdoor senior economist Daniel Zhao

The increase in worker pay over the past 12 months fell to 2.9% in September from 3.2%, according to the latest government figures released Friday.

The top cities for pay growth in September are San Francisco (up 3% on the year with a $73,861 median base pay), Atlanta (also up 3% on the year with a $56,059 median base pay) and Los Angeles (up 2.8% with a $63,526 median base pay), Glassdoor said. Warehouse associates saw the fastest pay growth in September (up 6.3% on the year with a $42,864 median base pay).

Unemployment hit a 50-year low of 3.5% in September, according to the government snapshot of the labor market released Friday. The data showed that the economy added 136,000 new jobs last month. Economists polled by MarketWatch had forecast a 150,000 increase. This is the slowest pace of job growth in four months, as businesses grew more cautious about hiring, but employment gains for August and July revised up by a combined 45,000.

“Today’s growth is a far cry from the blockbuster job market in 2018,” said Glassdoor senior economist Daniel Zhao. “Growth in job openings slowed to 3.5% in September, continuing a long-running trend of modest growth in 2019.” That compares to more than 10% this time last year. “Job openings on Glassdoor remain just shy of the 6 million mark, indicating a tight labor market with employers still looking for increasingly scarce workers to fill their open roles,” Zhao said.

“Despite a rocky August with recession chatter near fever pitch, the labor market continues to sustain the economic expansion,” the report said. “Crucially, the Federal Reserve’s decision in September to cut interest rates was in spite of, and not because of, the labor market. Additionally, while the trade war has negatively impacted sectors like manufacturing, consumer spending has been resilient.”

Software developers, physical therapists and physician assistants crop up frequently among the highest-paid and fastest-growing jobs in every U.S. state.

“The risk, however, is that the latest and forthcoming rounds of tariffs on consumer goods could extend the trade war’s impacts to the broader economy,” it added. “For the time being, Glassdoor data suggests that the labor market is shrugging off trade uncertainty and continuing to plow forward and sustain the economic expansion.”

Software developers, physical therapists and physician assistants crop up frequently among the highest-paid and fastest-growing job openings in every U.S. state, according to a separate analysis by CareerBuilder, another jobs and careers site. That site analyzed government data to project the careers most likely to be lucrative and in demand. Most of these jobs require some level of college education.

Software developers had a median pay of $105,590 per year or $50.77 per hour last year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics; it says there’s a higher-than-average outlook for job openings (up 24% nationwide between 2016 and 2026). Physical therapists had a median pay of $87,930 per year or $42.27 per hour last year, the BLS said, and also have a higher-than-average outlook for job openings (a projected 28% increase nationwide between 2016 and 2026).

Home-health and personal-care aides were among the lowest paid and the fastest growing job openings in every U.S. state and Washington, D.C., and require a high-school diploma or equivalent. The median pay for these jobs was $24,060 per year or $11.57 per hour, according to the BLS. But the demand for these jobs is projected to increase by 41% between 2016 and 2026.

A separate report by the U.S. News & World Report on the best jobs of the year lists software developers as No. 1. The position offers flexible hours and remote work opportunities, while investing in individuals’ personal and professional development. Like data scientists, software developers have a median annual salary of more than $100,000. They’re employed in computer systems design, manufacturing and finance. Physician assistants were No. 2, followed by dentists.

Updated: 10-14-2019

Drawn by the Salary, Women Flock to Trucking

Truck drivers typically are paid by the mile, regardless of gender. But safety issues remain.

Last year, Rebekah Koon left her job as an assistant manager of a gas station in Fort Bragg, N.C., to train as a truck driver, inspired by watching her uncle hit the road as a long-haul trucker when she was growing up.

“I thought it was really cool, like an extended camping trip,” she says.

Ms. Koon, 28, is part of a new wave of women breaking into trucking. The number of female truckers increased by 68% since 2010 to 234,234 in 2018, though women still account for just 6.6% of the trucking workforce, according to the American Trucking Associations, a trade group.

One Big Reason: Equal Pay.

“There are many different types of driver pay in the industry, including by the mile, per load, hourly, and even salary in some cases,” says ATA economist Bob Costello. “In all cases, there is no distinction between male or female. If you go to a fleet and ask how much drivers are paid, it is by experience level, routes, etc., not gender-specific.”

The median annual wage for heavy and tractor-trailer truck drivers is $43,680, according to the U.S. Labor Dept. Light truck and delivery-service drivers make a median of $32,810.

Ms. Koon’s new gig hauling for Cargo Transporters has tripled her salary, she says. “It’s a great lifestyle.”

The growth in women in the industry comes as demand for transportation workers is high, boosted by the expansion of e-commerce, says Frank Steemers, an economist at the Conference Board, a nonprofit research firm. Amid a tight labor market, employers are turning to new demographic groups to fill these positions, he says.

“The steering wheel knows no gender,” says Deb La Bree, 53, a former cosmetologist who lives in Missouri and has been driving a truck since 2007.

Open Road

The number of women in trucking has jumped almost 70% since 2010.

Some drivers and women’s advocates say the industry has begun to change to make it more accommodating to women. “New technology and equipment make truck driving a job that’s more geared toward women,” says Lindsey Othmer, 26, who drives for XPO Logistics out of Fife, Wash.

For example, XPO trucks now have a more modern transmission system that makes them less strenuous to drive, says Meghan Henson, chief human-resources officer at XPO, one of the largest transportation and logistics companies in the U.S. And at many companies, drivers, regardless of sex, don’t physically load and unload goods anymore.

“The industry has changed,” says Ellen Voie, president and chief executive of Women in Trucking, a nonprofit that encourages women to join the profession.

But the share of women drivers remains small. “Some trucking companies have put an emphasis on female drivers, but the highest percentage of female drivers we have seen is around 20% for those fleets,” economist Bob Costello says in an ATA report.

And some advocates and industry officials say women face obstacles when it comes to joining—and feeling comfortable in—the industry.

Learning to truck requires many hours on the road with a trainer, and most of them are men. Some companies try to match women with female trainers, but there aren’t always enough, says Ms. Voie.

Then there are on-the-job concerns. A 2017 survey by Women in Trucking asked female drivers how safe they felt at work; the average response was 4.4 out of 10.

One of their main concerns is finding a safe, well-lit place to park overnight when there aren’t enough spots. If truckers arrive at a truck stop at the end of their working day and find it full, they may have to keep driving past their limit or park illegally on the side of the road.

Driver Cecilia Hylton, 24, says her father, who is also a trucker, taught her to loop her seat belt through the door handle and buckle it so the door can’t be opened from the outside while she’s sleeping.

Ms. Voie is optimistic that the industry will find ways to tackle issues such as training because of the shift in attitude she’s witnessed. “Twelve years ago, everyone said, ‘We just want good drivers.’ Now, the carriers are saying, ‘We want more women. Help us do that.’ ”

Updated: 12-7-2019

FedEx Goes Deep Into Mississippi Delta to Find Workers

To fill its vast workforce, delivery giant ferries 200 people four hours round trip to work the night shift at its Memphis hub.

Inside the nearly barren living room of her apartment, Mary Harris slips into a reflective yellow jacket adorned with the FedEx Corp. logo as the sun begins to set.

It is Monday. She won’t be back home until around sunrise on Wednesday.

In between, Ms. Harris will drive an hour northwest to Cleveland, Miss., from where she will make three four-hour round trips curled up on a bus to Memphis, Tenn. In Memphis, she will do two overnight shifts and one day shift—each five hours long—helping to move and sort millions of packages at FedEx’s primary air hub.

FedEx has tapped deep into the Mississippi Delta to find workers for the largest facility in its world-wide supply chain. Lured by the chance to work for a global company and earn hourly wages starting at $13.26, some 200 workers gather in a Walmart parking lot in Cleveland, Miss., five nights a week to board buses bound for Memphis.

“They’re important to the daily operation,” said Barb Wallander, a senior vice president of human resources at FedEx. “We depend on them.”

The connection with Cleveland, a two-hour drive from Memphis, is an unlikely cog in a machine that gets the surge of holiday shipments to homes quickly. FedEx and its rivals are expected to carry more than 2.4 billion global packages between Thanksgiving and the end of the year, or twice as many parcels as they handled in 2013, according to SJ Consulting Group estimates.

The busing program, which runs year-round and is nearing its first anniversary, highlights the lengths delivery giants have to go to staff their operations at a time when unemployment is low, especially around the largest hubs. In Memphis, the unemployment rate is 3.8%, just above the 50-year low of 3.5% nationwide. In Louisville, Ky., where United Parcel Service Inc. runs its main air hub, the unemployment rate is 3.2%.

Ms. Harris said opportunities like the one at FedEx are no longer available in Greenwood, a shrinking rural town that welcomes visitors with a sign that reads “Cotton Capital of the World.”

“It is in my blood to work hard for what I need and want,” said the 39-year-old, who started working for FedEx last December. She drives an hour to get to Cleveland to start her bus commute.

In Bolivar County, where Cleveland is, the unemployment rate stands at 6.8%, according to the Mississippi Department of Employment Security. A drug manufacturer recently closed a factory there, and an auto-parts maker expects to close a plant soon.

The situation drew FedEx to host a job fair in Cleveland in November 2018, just ahead of the busiest period for the shipping industry. The city has a population of 12,000.

Ms. Wallander said FedEx expected not much more than a few dozen attendees. Instead, about 500 people showed up, said Pam Chatman, a retired news director who posted word of the event on her Facebook page. FedEx later staged a hiring center in a church fellowship center, where it did drug screening and orientation.

A major hurdle was how workers would get to Memphis, 115 miles away. Many didn’t have cars.

FedEx committed to providing free bus rides for the workers, part of a three-year pilot program. “If the jobs are not coming to the Mississippi Delta, then we have to take the people to the jobs,” said Ms. Chatman, who reached out to FedEx volunteering to coordinate the initial job fair.

Workers collect around 7 p.m. in the Walmart parking lot on North Davis Avenue, one of two retail corridors that cross through Cleveland. They are easy to spot in their FedEx-issued jackets entering the big-box retailer or adjacent Murphy’s gas station to grab chicken, McDonald’s or other snacks before three Delta Bus Lines coaches pull up.

Kinyuna Cannon, 25 years old, has been working for FedEx for the past four months. The starting wage was well above the $7.85 an hour she earned at her last job at a nursing home. “It is the transportation and the pay,” she said of the appeal of the FedEx job, which are part-time positions that provide health and retirement benefits.

She boards the middle bus, settling into the black leather seats for the ride to Memphis. The caravan of headlights cuts through the rural highway on a moonless night.

Two hours later, the buses pull into an employee parking lot across from the Memphis International Airport. The workers disembark, cross a covered overpass and traverse the security checkpoint. They blend in among the 7,000 workers that night, helping to unload 150 cargo planes, sort their packages and reload them to the next destination.

Walter Kirkeminde, FedEx senior manager of operations, says turnover among the workers coming from Mississippi is lower than the locals, who have more opportunity to switch jobs if the overnight schedule proves unmanageable. He was skeptical of the staying power and initially thought the bus would last a few weeks. “That would be my limit,” he said.

FedEx has since started busing workers for shifts to a sorting facility for its Ground division in Olive Branch, Miss. It has attempted to add buses to other regions with similar demographics to Cleveland. “We haven’t had the same response rate,” Ms. Wallander said.

The Mississippi Delta has ties to the leaders of both FedEx and UPS. FedEx founder Fred Smith was born in nearby Marks, Miss., the son of a bus- company owner, before starting his overnight delivery company in Memphis. UPS CEO David Abney was born in Cleveland and started working at UPS in the city to pay his way through the local college.

Ms. Harris, who grew up in the Delta, recalls past jobs she had in the area, including in fish-processing plants and driving trucks, and how she spent months moving among friends’ houses and for a time in a shelter before she went to the FedEx job fair.

Now, her 21-year-old son, Denzell, also works at FedEx, and she is picking up extra shifts. After the first night, she quickly turns around on the bus to work the day shift in Memphis. Once that is done, she returns back to Cleveland. With not enough time to head home, she makes a brief stop at her son’s father’s house to freshen up.

She has hopes of progressing at FedEx, perhaps working on the aircraft she helps load. “I thought FedEx was a godsend,” she said. “It helped so many people get out of their rut.”

Share Your Thoughts

Have you had to do extra shifts or travel to meet work demands during the holidays? How was that experience?

Updated: 12-9-2019

American Factories Demand White-Collar Education for Blue-Collar Work

Within three years, U.S. manufacturing workers with college degrees will outnumber those without.

College-educated workers are taking over the American factory floor.

New manufacturing jobs that require more advanced skills are driving up the education level of factory workers who in past generations could get by without higher education, an analysis of federal data by The Wall Street Journal found.

Within the next three years, American manufacturers are, for the first time, on track to employ more college graduates than workers with a high-school education or less, part of a shift toward automation that has increased factory output, opened the door to more women and reduced prospects for lower-skilled workers.

“You used to do stuff by hand,” said Erik Hurst, an economics professor at the University of Chicago. “Now, we need workers who can manage the machines.”

U.S. manufacturers have added more than a million jobs since the recession, with the growth going to men and women with degrees, the Journal analysis found. Over the same time, manufacturers employed fewer people with at most a high-school diploma.

Employment in manufacturing jobs that require the most complex problem-solving skills, such as industrial engineers, grew 10% between 2012 and 2018; jobs requiring the least declined 3%, the Journal analysis found.

At Pioneer Service Inc., a machine shop in the Chicago suburb of Addison, Ill., employees in polo shirts and jeans, some with advanced degrees, code commands for robots making complex aerospace components on a hushed factory floor.

That is a far cry from work at Pioneer in the 1990s, when employees had to wear company uniforms to shield their clothes from the grease flying off the 1960s-era manual machines used to make parts for heating-and-cooling systems. Pioneer employs 40 people, the same number in 2012. Only a handful of them are from the time when simple metal parts were machined by hand.

“Now, it’s more tech,” said Aneesa Muthana, Pioneer’s president and co-owner. “There has to be more skill.”

Pioneer, which makes parts for Tesla vehicles and other luxury cars, had its highest revenue last year, Ms. Muthana said. The company’s success mirrors that of other manufacturers that survived the financial crisis.

Improvements in manufacturing have made American factories more productive than ever and, despite recent job growth, require a third fewer workers than the nearly 20 million employed in 1979, the industry’s labor peak.

Manufacturers added 56,000 jobs this year compared with 244,000 jobs through this time last year. Automation and competition from lower-wage countries have contributed to declining U.S. manufacturing jobs.

The industry’s specialized job requirements have narrowed the path to the middle class that factory work once afforded. The new, more specialized manufacturing jobs pay more but don’t help workers who stopped schooling earlier. More than 40% of manufacturing workers have a college degree, up from 22% in 1991.

“The workers that remain do much more cognitively demanding jobs,” said David Autor, an economics professor at MIT.

Looking ahead, investments in automation will continue to expand factory production with relatively fewer employees. Jobs that remain are expected to be increasingly filled by workers from colleges and technical schools, leaving high-school graduates and dropouts with fewer opportunities. Manufacturing workers laid-off in years past also will see fewer suitable openings.

“It’s just not the case that bringing back manufacturing will be good for low-and-middle-skill workers,” said Mr. Hurst, who along with colleagues have studied the increasing demands of factory workers.

Robot Wranglers

Advantage Conveyor Inc. in Raleigh, N.C., spent more than $2 million over the past decade on machines that cut and bend metal and plastics for the conveyor belts it builds. New machines allow technicians to make more parts per worker compared with the era when employees fashioned parts by hand.

Some of the workers were reassigned; others were laid off. “All of that menial labor moved to skilled labor,” said Vann Webb, company president. “You virtually have to have a two-year degree to work in our shop.”

Joshua Dallons, 28 years old, had hoped to become a nuclear engineer, but juggling college classes and a 30-hour-a-week grocery job was too much.

“I had that crisis,” Mr. Dallons said. “Do I want to keep pursuing engineering, or do I want to pursue this sort of job where I can quickly get into the field and quickly start making money?”

He decided to complete a training program in welding and was hired by Advantage in 2014. Mr. Dallons now works at a computer, designing conveyor layouts. He makes more than $25 an hour.

Large manufacturers also are tilting their workforce toward higher skilled, educated employees. Around 70% of new hires this year at Honeywell International Inc. ’s aerospace business have at least an associate degree, said Darren Kosel, a Honeywell plant manager.

The company isn’t a place for factory workers who want to just punch in and punch out every day, Mr. Kosel said: “If you want to be one of those people, you won’t be successful here.”

At a Caterpillar Inc. plant in Clayton, N.C., investments in technology help a single shift of workers produce the small-wheel loaders that four years ago would have taken two shifts.

The Harley-Davidson Inc. ’s engine plant in Milwaukee has robotic arms to ferry motorcycle pieces, taking over the tough, repetitive work formerly done by employees, said plant manager Chuck Statz. The machines have made the workplace safer, he said, mirroring a national trend. In 2018, factory workers were hurt at half the rate as in 2003.

Harley-Davidson employed 2,200 unionized manufacturing workers in 2018, 400 fewer than in 2014, which the company attributed to several factors. Caterpillar reported that it had 10,000 unionized workers at the end of 2018, down from 15,000 in 2007 During the same period, the equipment maker’s revenue climbed 20%.

A recent search of all Caterpillar’s U.S. job posts show that more than four in five require or prefer a college degree. A majority of the company’s production jobs called for a degree or specialized skill.

High Risk

Ms. Muthana faced a hard choice in 2012: whether to invest millions of dollars in automated manufacturing and training, or to retire and close Pioneer, the company her uncle started 30 years ago.

In the old days, the factory’s oil-sputtering machines were adjusted by two dozen workers wielding foot-long wrenches. At the end of their shifts, they were covered in grease and metal shavings.

Pioneer’s biggest clients, makers of heating and cooling systems, switched to cheaper foreign suppliers, Business fell 90% in one year. And the company owed more to suppliers than its outstanding orders could cover.

Ms. Muthana sat in the company parking lot on October 15, 2012, looking at the cars of her employees. “If I closed my doors, where were they going to go?” she recalled thinking.

Rather than close the plant, she hired Pioneer’s first salespeople. They found vehicle makers that needed complex metal components that Pioneer could make more profitably than the parts for heaters and air conditioners.

The problem was that Pioneer’s old machinery couldn’t make the parts fast enough. So Ms. Muthana sought machines that could be programmed to precisely cut and drill the intricate parts in a single operation.

Pioneer had little experience with such advanced equipment, Ms. Muthana said, but she persuaded suppliers to help her install and set up the machines, as well as train employees to use them.

“We put a lot of money on her floor at one time with minimal guarantees that we were going to get that money back,” said Dave Polito, owner of her main machine supplier. Ms. Muthana said she has now spent more than $6 million on new technology, largely for machines and software.

The machines can make one complex part every six minutes, compared with 45 minutes of work on multiple machines once needed to produce a single part. Learning how wasn’t easy for longtime Pioneer employees.

Fernando Delatorre, who operated the older machines at Pioneer for 14 years, struggled to memorize the codes used to program the new machines.

“I wasn’t into computer things, learning all these numbers,” said Mr. Delatorre. He earned $16.50 an hour when he left Pioneer in 2017 for a construction job that paid more.

For Ms. Muthana, losing or firing longtime employees was the toughest part of her factory’s transition. About 10 of the company’s 40 workers remained. Just one of them operates a special grinder that hasn’t been computerized.

“I saved those jobs, and I gave them the opportunity,” she said, “but then most of the team is no longer here anyway.”

On a recent morning, Pioneer workers inspected parts that the automated equipment had made on their own overnight. They took digital measurements to make sure the parts matched customer specifications. A screen overhead detailed how efficiently each machine was operating.

A yellow light on one machine caught the eye of technician Stacy Czyzewski. A cutting tool was due to be replaced. She opened the machine’s enclosure, which seals in the oil and metal scraps. Using a small Allen wrench, she popped out the worn part and replaced it.

She punched codes on the machine’s keypad from memory and marked the repair on her iPad. Ms. Czyzewski wiped her hands on a towel. Her black polo shirt, emblazoned with Pioneer’s logo, was spotless.

Ms. Czyzewski had previously worked five years cleaning equipment at an Altria Group Inc. chewing tobacco plant. When it closed in 2017, a grant helped Ms. Czyzewski pay for a four-month training program where she learned to operate the machines used at Pioneer.

In a room at the center of the Pioneer factory, Rachith Thipperi converts customer orders into 3-D blueprints that are used to program machines. He started work at Pioneer as an intern while studying for a master’s degree in mechanical engineering at the University of Illinois at Chicago. Mr. Thipperi saw a future in the modern American factory.

“There are people who are stuck in old manufacturing,” he said, “but there is also this innovative and growth aspect of it.”

Production workers at Pioneer start at $14 an hour and rise to $27 an hour with experience. Before investing in modern machinery, worker pay started near minimum wage, which was $8.25 an hour around the time the company was transforming in 2010.

Inspirational inscriptions decorate the walls of the Pioneer factory. “The most dangerous words are we’ve always done it that way,” one said. The boss has lunch with her 40 employees each quarter. Half are women.

Ms. Muthana attends college career fairs to find workers with skills and a desire to learn. “I’m willing to give you the opportunities,” she said. “But if you’re not willing to change, and you’re not willing to get out of your comfort zone, there’s nothing I can do.”

Updated: 12-9-2019

Five Cities Account for Vast Majority of Growth in Tech Jobs, Study Finds

The forces that prompt this clustering effect among tech firms is widening the skills divide within U.S.

The forces that are driving the nation’s top technology talent to just a handful of cities have intensified in recent years, leaving much of the nation behind as the U.S. becomes a more digital economy, according to a new study.

Just five metropolitan areas—Boston; San Diego; San Francisco; Seattle; and San Jose, Calif.—accounted for 90% of all U.S. high-tech job growth between 2005 to 2017, according to the research by think-tank scholars Mark Muro and Jacob Whiton of the Brookings Institution and Rob Atkinson of the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation.

The nation’s 377 other metro areas accounted for 10% of the 256,063 jobs created during that period in 13 high-tech industries such as software publishing, pharmaceutical manufacturing and semiconductor production. Among the smaller cities that gained tech jobs were Madison, Wis.; Albany, N.Y.; Provo, Utah; and Pittsburgh.

The result is increased concentration of high-tech resources in just a few places and a strengthening of economic forces that are dividing the nation.

Tech industries find they are most productive when they have resources clustered in few places. Such clustering—which economists call “agglomeration”—allows for the fast spread of new ideas and a concentrated talent pool from which businesses recruit. The forces of agglomeration, economists say, run counter to the idea that technology might allow people to work from anywhere, even in remote places.

The trend is creating problems for the cities that have these concentrations of workers and for those places that don’t. High-tech cities like San Francisco and Boston are becoming increasingly unaffordable as home prices soar, while cities outside of these high-tech hubs are missing out on the dynamism that technology creates, Mr. Muro said.

“The superstar places are becoming extremely expensive, choked with traffic and struggling with big social costs like inequality gone wild and homelessness,” Mr. Muro said.

The authors looked at industries with high concentrations of research and development spending and high concentrations of workers with degrees in science, technology, engineering and math.

Some big cities were left behind. Combined, the Washington, D.C., metro area; Dallas; Philadelphia; Chicago; and Los Angeles lost more than 45,000 high-tech jobs between 2005 and 2012, according to the study. Many small cities across the heartland also lost tech jobs.

Mr. Muro noted that the Washington area will likely make up for the loss with the addition of an Amazon. com Inc. headquarters, but others run the risk of falling further behind in the race for tech talent.

“Whole portions of the nation may now be falling into ‘traps’ of underdevelopment,” the report said.

The report calls for a national effort to support technology investment in areas outside of the big centers, featuring federal government spending of $100 billion on research and development, workforce development, tax benefits and other programs over 10 years in the nation’s heartland.

“There are tremendous inefficiencies with the status quo,” Mr. Muro said.

Updated: 12-18-2019

The Demographic Threat To America’s Jobs Boom

As fertility falls and immigration tightens, the U.S. is losing its demographic advantage over other countries.

The U.S. job market continues to blow through expectations, generating 200,000 new jobs month after month and driving unemployment far below what economists thought a decade ago was the lowest possible level.

The main reason is that the economy tends to keep creating jobs until interrupted by a recession. The current expansion has now lasted a record 10-plus years. So long as the usual recession triggers—rising inflation and interest rates, or financial excess—remain absent, job creation should continue.

Yet eventually it will hit a constraint: The U.S. will run out of people to join the workforce. Indeed, this bright cyclical picture for the labor market is on a collision course with a dimming demographic outlook. While jobs are growing faster than expected, population is growing more slowly. In July of last year, the U.S. population stood at 327 million, 2.1 million fewer than the Census Bureau predicted in 2014 and 7.8 million fewer than it predicted in 2008. (Figures for 2019 will be released at the end of the month.)

The U.S. fertility rate—the number of children each woman can be expected to have over her lifetime—has dropped from 2.1 in 2007 to 1.7 in 2018, the lowest on record. From 2010 through 2018, there were 3 million fewer births and 171,000 more deaths than the Census Bureau had projected in 2008. Death rates, already rising because the population is older, have been pressured further by “deaths of despair”—suicide, drug overdoses and alcohol-related illness.

Aging doesn’t spell economic doom: Germany’s population is flat and Japan’s is falling, yet both boast lower unemployment than the U.S. But in the long run, job creation is constrained by the number of people of working age, which is why the International Monetary Fund puts Germany’s long-run growth rate at 1.3% and Japan’s at 0.6%, both lower than the U.S. at 1.9%.

The latest employment data underscore these dynamics. In the 12 months through November, the number of people working rose 1.2% from the prior 12 months, according to the Labor Department. That was slightly faster than 1% growth of the labor force—the number of people working or looking for work—and thus the unemployment rate fell. Labor-force growth was in turn faster than the 0.6% growth in the working-age population. As a result, the share of working-age people who are in the labor force, known as the labor-force participation rate, rose.

Unemployment is already as low, and possibly lower, as many economists think can be sustained in the long run.

While the participation rate, at 63.2%, is lower than its 1990s peak of 67%, Stephanie Aaronson, head of economic studies at the Brookings Institution, said most of the decline is demographic and won’t easily reverse. More of the working-age population is over 60 and has thus retired—or will soon.

Young adults are staying in school longer. Participation of prime-age women, those aged 25 to 54, is already back to historic highs. The participation of prime-age men, especially those without a college education, has been trending down for decades. Low unemployment could keep drawing people into the labor market and maintain participation over 63%, but she doubts it can go higher without big changes in government policies.

The U.S. has had two longstanding demographic advantages over other countries: higher fertility and immigration. Both are eroding. Since 2008, the U.S. fertility rate has gone from well above to roughly in line with the average for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a group 36 mostly developed economies.

Mark Mather, a demographer at the Population Reference Bureau, said analysts initially blamed the drop in births on the recession, and expected it to bounce back as people felt more economically secure. In fact, he says it started before the recession as young adults delayed marriage and children, which will likely result in fewer children over their lifetimes. “We don’t expect to see a bounce back any time soon.”

Meanwhile, the inflow of foreign migrants to the U.S. has been trending flat to lower, while trending flat to higher in other countries. Last year, the foreign-born population expanded by a historically low 200,000, according to the Census Bureau. The exact reasons are unclear. The illegal immigrant population had stopped growing before President Trump took office. Legal immigration remained above 1 million through 2018.

Mr. Trump has proposed keeping legal immigration levels constant, while shifting the composition more toward skills and away from family reunification. But that still implies a declining rate of immigration relative to overall population. And his administration has moved to discourage some legal immigration, such as those who might need federal benefits.

Demographic trends aren’t etched in stone. Japanese labor-force participation, in particular by the elderly, has risen in recent years and German fertility is on the rise, though still quite low. A prolonged expansion could have similar effects in the U.S., and indeed there is some evidence fertility stabilized this year. Political cooperation could one day pave the way to more immigration.

But until then the U.S. cannot assume it is immune to the demographic downdraft holding back Germany and Japan.

Updated: 4-21-2021

Stimulus Checks And Unemployment Insurance Keep Job Seekers On The Sidelines

The Job Market Is Tighter Than You Think.

Solid wage growth and unfilled openings point to much less slack than after previous recession.

One set of numbers shows a labor market in dire straits. Total employment, despite March’s jump, is still down 8.4 million from its pre-pandemic peak, on a par with the worst point of the 2007-09 recession and its aftermath.

While the unemployment rate at 6% is lower than in 2009, it is above 9% when people not counted as unemployed because they dropped out of the labor force or were misclassified are added back, according to the Federal Reserve. In short, the labor market seems awash in slack, with job seekers swamping demand for workers.

Weirdly, that isn’t what a different set of numbers suggests. It shows a labor market starting to look, well, tight.

Consider wages. In a truly bad labor market, desperate workers would accept much lower pay, dragging down earnings growth. That hasn’t happened.

The Labor Department’s widely followed average earnings data are distorted by the disproportionate drop in low-wage work, so you need to consult measures that filter out these compositional effects. One, median wage growth as tracked by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, was 3.4% in February, barely changed from before the pandemic.

Another, the Labor Department’s employment cost index, shows earnings up 2.8% in the fourth quarter of 2020, compared with 3% a year earlier. In 2010, both measures of wage growth fell below 2%.

Another sign of a tightening labor market: employers having trouble staffing up. In October 2009, businesses contacted for the Fed’s beige book, an anecdotal survey of economic conditions, overwhelmingly described the labor market as weak and wage pressures as subdued.

By contrast, this month’s beige book reported shortages of drivers; entry-level, low-wage and skilled workers; child-care and information-technology staff; specialty trades; and nurses. “A homebuilder related that a landscaper had hired 20 laborers in early February and none showed up for work,” the latest beige book said. “One restaurant had begun offering $1,000 if workers stayed for at least 90 days.”

One shouldn’t put too much weight on anecdotes, but these are corroborated by data. Some 7.4 million jobs were open in February, above the pre-pandemic level. By contrast, job vacancies plummeted by half in 2007-09. A mismatch might be at work: sectors and regions unscathed by the pandemic want to hire, but the available workers are in the wrong place or have the wrong skills. Nonetheless, job vacancy rates are above pre-pandemic levels in most sectors, even leisure and hospitality.

So why does one set of numbers suggest the labor market is slack while another suggest it is tight? The discrepancy goes back to how this recession was fundamentally different from the previous one. The 2008-2009 financial crisis wiped out wealth and dried up credit.

That sapped demand for goods and services as consumers stopped spending, and for workers as employers stopped hiring. By contrast, the pandemic clobbered both demand for workers as businesses closed, and the supply as workers withdrew to look after their children or their health.

As businesses reopen and stimulus checks juice sales, the demand for workers is now recovering, but the supply of workers, not so much. Adjusted for population growth, the labor force—people working or looking for work—is roughly five million smaller than before the pandemic.

Only a small share of those labor market dropouts want a job. Covid-19 is keeping most of the others out of the job market. A Census Bureau survey in late March found that 2.6 million people weren’t working because they were sick or caring for someone who was, and 4.2 million were afraid of catching or spreading the virus.

(The two groups might overlap.) Indeed, fear might be the single most important difference between this recession and its predecessors. Millions are also caring for children, but it wasn’t clear how many were because of Covid-19 closures.

Stimulus checks and unemployment insurance, which has been extended to gig workers and made more generous, might also have kept potential job seekers on the sidelines. Several studies found that the aid didn’t depress employment last year because there were no jobs to be had. That may be changing as demand for workers ramps up.

All in all, while unemployment is indeed elevated, the job market isn’t as “loose” as the 8.4 million shortfall suggests. This partly undercuts the rationale for the aggressive fiscal and monetary stimulus injected into the economy: to fuel spending that soaks up all of those out-of-work people. Many simply aren’t available to be hired.

That is likely to change. As vaccination spreads, the virus-related obstacles to working should recede and economists expect the labor force to rebound. That is a Goldilocks scenario: historically high levels of employment and the sort of robust wage growth workers, especially the lowest-paid, were enjoying pre-pandemic.

But what if workers are slow to return? As stimulus-stoked demand for labor meets stubbornly reduced supply, the result should be even faster wage gains for those who do work, and one more reason to worry about inflation.

Updated: 9-10-2021

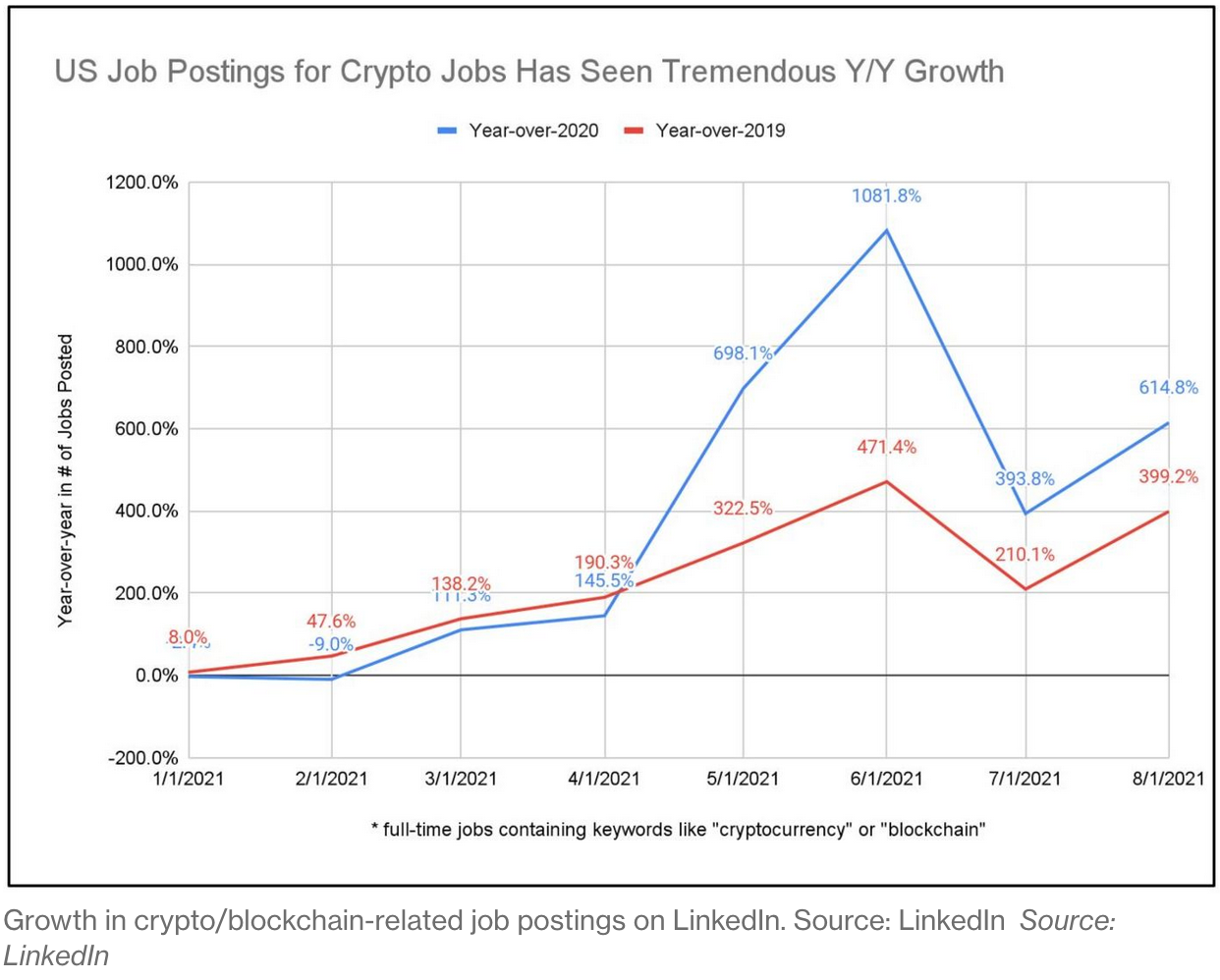

How The Crypto Workforce Changed In The Pandemic

“I see my team blossoming in this lockdown. They are more honest about what they can and cannot do. And it’s my role as CEO to support them.”

The pandemic has put hundreds of thousands of businesses out of action, saw others fold and decimated great swathes of the economy.

But, crypto thrived in this distributed environment. As the world clamped down and everyone was forced to decentralize, the crypto world shone.

Perhaps crypto, born of a crisis, is most at home in one. Working from home is where we all have spent most of this crisis.

Gaurang Tovekar is the CEO and co-founder at Indorse, a blockchain-powered enterprise SaaS platform.

He says the company was perfectly placed to ride out the upheaval as the entire team has never been in the same physical location since the company’s inception.

“Although the pandemic accelerated remote work and the adoption of decentralization in the workforce globally on an unprecedented scale, it was already a norm within the crypto industry well before the pandemic struck.”

He points out that although the company once had offices in Singapore and London, he’d already swapped them out for hot desks in co-working spaces before the pandemic.

“That way, those of us who want to meet up once or twice a week and bond socially can still do so in the office while working from home the majority of the time.

“We have adapted our work styles and got used to this new normal in the last year and a half. I am sure that we as a company will not lease swanky office spaces any time soon, but rather provide better flexibility and other perks that make working from home more pleasurable for our team,” he concludes.

Office As A Luxury?

Stefan Rust, the former CEO of Bitcoin.com and now CEO and co-founder of Sonic Capital, is taking a different approach to remote working. He’s just signed a lease on a “swanky office” in Hong Kong – but at a substantial discount. He intends to use this real estate luxury as a perk to benefit his mostly remote workforce.

“I plan on creating large open plan spaces with sofas, TVs, screens and hot desks. I want people to be able to come in and relax, enjoy time with their co-workers, conduct meetings or just chill. The new office has to be a place where people want to come — it’s about choice,” explains Rust.

So, perhaps as pandemic restrictions wind back, an office will be seen as a luxury perk for tech and crypto companies, a central clubhouse that people use how and when they want.

Ramadan Ameen, CFO for privacy startup Panther Protocol, reflects that his international team was put in place during the pandemic in Jan. 2021. Not only has his team never all been in the one location, but the majority of the twenty staff also have never met each other in person. For Ameen, a team meetup and bonding session are significantly ahead of company offices, for now.

“The co-founders have met, but the team is spread out across North and South America, Asia and Europe.