The Fed Is Setting The Stage For Hyper-Inflation Of The Dollar (#GotBitcoin)

Policy makers have begun talking about letting the inflation rate rise above its 2% target. Look for a formal statement soon. The Fed Is Setting The Stage For Hyper-Inflation Of The Dollar (#GotBitcoin)

Related:

Ultimate Resource On A Weak / Strong Dollar’s Impact On Bitcoin

Hyperinflation Concerns Top The Worry List For UBS Clients

Deutsche Bank Short US Dollar Index (USDX)

Juice The Stock Market And Destroy The Dollar!! (#GotBitcoin)

Bloomberg: Americans Trade Depreciating Dollars For Bitcoin

Dollar On Course For Worst Month In Almost A Decade (#GotBitcoin)

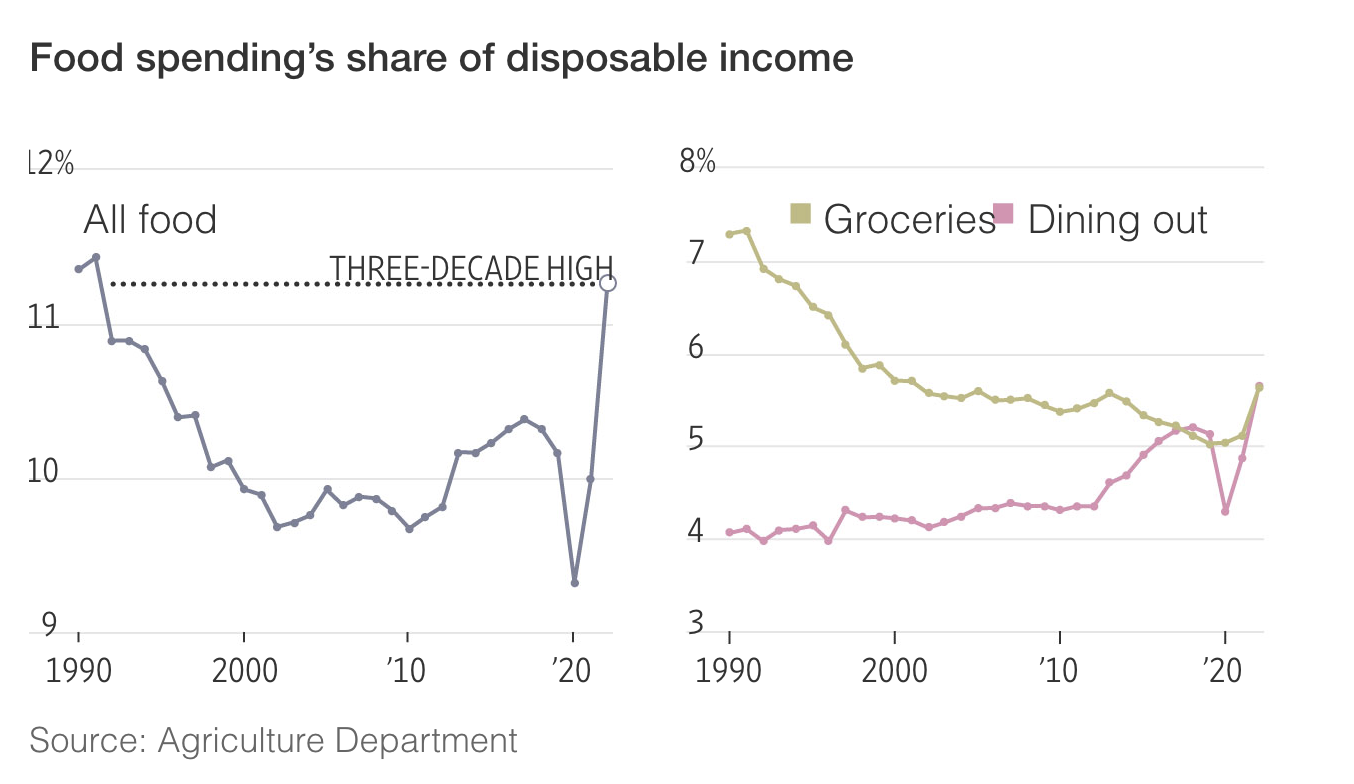

Housing Insecurity Is Now A Concern In Addition To Food Insecurity

Families Face Massive Food Insecurity Levels

US Troops Going Hungry (Food Insecurity) Is A National Disgrace

Ever-Growing Needs Strain U.S. Food Bank Operations

Dollar Stores Feed More Americans Than Whole Foods

The Fed’s traditional Phillips curve approach to forecasting inflation, which relies on the theory that inflation accelerates as unemployment falls, was widely criticized during the most recent economic recovery. Inflation remained quiescent in the wake of the Great Financial Crisis even as the unemployment rate fell to 3.5%, well below the 2012 high estimate of the natural rate, or 5.6%.

The Fed’s commitment to Phillips curve-based inflation forecasts induced it to raise interest rates too early in the cycle and continue to boost rates into late 2018 even as faltering markets signaled the hikes had gone too far. The Fed was eventually forced to lower rates 75 basis points in 2019 to put a floor under the economy. Inflation remained stubbornly below the Fed’s 2% target throughout that period.

Faced now with the prospect of another prolonged period of low inflation, Fed officials are signaling they will place less emphasis on Phillips curve estimates when setting policy.

Fed Governor Lael Brainard said this week that “with inflation exhibiting low sensitivity to labor market tightness, policy should not preemptively withdraw support based on a historically steeper Phillips curve that is not currently in evidence.”

No longer are estimates of longer-run unemployment taken as almost certainly indicating the economy is at full employment. Instead, Brainard said the Fed should focus on achieving “employment outcomes with the kind of breadth and depth that were only achieved late in the previous recovery.” The Fed is going to try to run the economy hot to push down unemployment.

By de-emphasizing the Philips curve, the Fed loses its primary inflation forecasting tool. Instead of an inflation forecast, the Fed will rely on actual inflation outcomes to determine the appropriate time to change policy.

Brainard pointed out that “research suggests that refraining from liftoff until inflation reaches 2% could lead to some modest temporary overshooting, which would help offset the previous underperformance.”

Think about what she is saying. Traditionally, the Fed attempts to reach the inflation target from below, effectively using the unemployment rate to forecast inflation and then moderating growth such that projected inflation doesn’t exceed its target.

Brainard is saying the Fed should not tighten policy until actual inflation reaches 2%. Policy lags — the time between the Fed’s actions and the resulting economic outcomes — mean inflation will subsequently rise above 2%. The Fed would thus overshoot the inflation target and then return to the target from above.

Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia President Patrick Harker goes even further in a Wall Street Journal interview, saying “I don’t see any need to act any time soon until we see substantial movement in inflation to our 2% target and ideally overshooting a bit.”

Expect to see more Fed speakers also saying they want inflation at or above 2% before they tighten policy. Also expect to see something along these lines codified at in a policy statement.

This shift also has implications for the Fed’s ongoing review of policy, strategy, and communications. When Brainard talks about offsetting “previous underperformance,” she is giving a green light to a “make-up” strategy in which the Fed compensates for a period of below-target inflation with a period of above-target inflation.

The Fed’s current policy does not allow for such a strategy. The broad willingness to accept overshooting implies that the Fed’s policy review will conclude with a shift toward some form of average inflation targeting in which the central bank explicitly sets policy to compensate for errors such that inflation averages 2% over time.

The implication for financial markets is that the Fed expects to hold policy very easy for a very long time. They will reinforce this stance with enhanced-forward guidance and, eventually, yield-curve control.

As long as inflation remains below 2%, the Fed will push back on any ideas that they will tighten policy anytime soon.

And even inflation above 2% wouldn’t guarantee tighter policy if the Fed concluded the overshoot was transitory. Don’t doubt the Fed’s resolve to keep policy accommodative. They will keep reminding you if you forget.

Fed’s Harker Backs Allowing Economy To Run Hot Before Raising Interest Rates

Philadelphia Fed president backs no interest rate hike until inflation moves above 2% annual inflation target.

Philadelphia Fed President Patrick Harker on Wednesday said he would support a change in monetary policy where the central bank would let the economy run hot until inflation rises above the central bank’s 2% annual target before raising borrowing costs.

“I’m supportive of the idea of letting inflation get above 2% before we take any action with respect to the federal funds rate,” Harker said, in an interview on Bloomberg Television.

Harker is a voting member of the Fed’s interest rate committee this year.

On Tuesday, Fed Governor Lael Brainard also backed the idea of letting inflation get over 2% before the Fed takes any action to raise interest rates. This promise is called “foward guidance” at the central bank. Typically, the Fed would hike rates preemptively if it saw inflation surging.

Former Fed staffer, and now Fed watcher, Krishna Guha said he saw support rising for this new policy and strengthened forward guidance and said it was good for investors who want to take risks.

“Harker’s comments suggest growing momentum behind this view at the U.S. central bank and should continue to support risk-appetite as investors look ahead to the coming Fed pivot to a new phase of monetary policy in which the FOMC will make longer range commitments on both rates and quantitative easing,” Guha, now the vice chairman of Evercore ISI, said in a note to his clients.

Harker said that controlling COVID-19 was critical to restoring the health of the economy. He said he was “a little skeptical” that the July employment report would be as strong as the prior two month’s reports given the resurgence of the virus in the South and West.

Harker said he was revising down his forecast for economic growth as a result of the spread of the coronavirus.

In a webcast speech later Wednesday to the Center City Proprietors Association, Harker said he expected a negative 20% growth rate in the first half of the year, followed by a 13% gain in the second half. The result would be minus 6% for the entire year.

“That’s a much sharper recession than we experienced during the financial crisis,” he said.

“This is going to be a slow recovery. Until we get the virus under control, we can’t get the economy back to full throttle,” he said.

Updated: 7-22-2020

What’s Behind The Fed’s New Push To Promote Inflation?

Why the Fed’s strategy on inflation is changing and why the definition used by America’s central bank may be hurting regular people.

Fed To Allow For Periods Where Inflation Runs Above The Central Bank’s 2% Target

Central bankers look to change long-running strategy to encourage lower rates, shift unemployment-inflation dynamic.

The Federal Reserve is preparing to effectively abandon its strategy of pre-emptively lifting interest rates to head off higher inflation, a practice it has followed for more than three decades.

Instead, Fed officials would take a more relaxed view by allowing for periods in which inflation would run slightly above the central bank’s 2% target, to make up for past episodes in which inflation ran below the target.

“It would be a significant change in terms of how they are thinking about” the trade-off between employment and inflation, said Jan Hatzius of Goldman Sachs. “A lot of those things look very different now from the way they looked a few years ago,” he said.

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell hinted at the shift at a news conference last week when he said the central bank would soon conclude a comprehensive review of its policy-making strategy that began last year.

Mr. Powell initiated the review with an eye toward beefing up the Fed’s ability to counteract downturns in a world where interest rates are lower and more likely to remain pinned at zero.

Even before the severe shock from the coronavirus pandemic, the Fed had grown concerned about spells of low inflation that have bedeviled authorities in Japan over the past two decades and in Europe for the past decade.

The change being contemplated now is a way of essentially telling markets that rates will stay low for a very long time. Markets have likely already picked up on this change, given the continued declines in long-term interest rates.

The changes on their own will do little to provide more support to the economy right now because investors already understand that the Fed isn’t likely to raise interest rates for years, said Steven Blitz, chief U.S. economist at research firm TS Lombard. “It is a change at this point without meaning. It’s just words,” he said.

The Fed would formally adopt changes by altering a statement of long-run goals that it approves annually, something it last did in January 2019. “The changes we’ll make…are really codifying the way we’re already acting with our policies,” Mr. Powell said last week.

One way for the Fed to do that would be to amend that document to say inflation should average 2% “over time.”

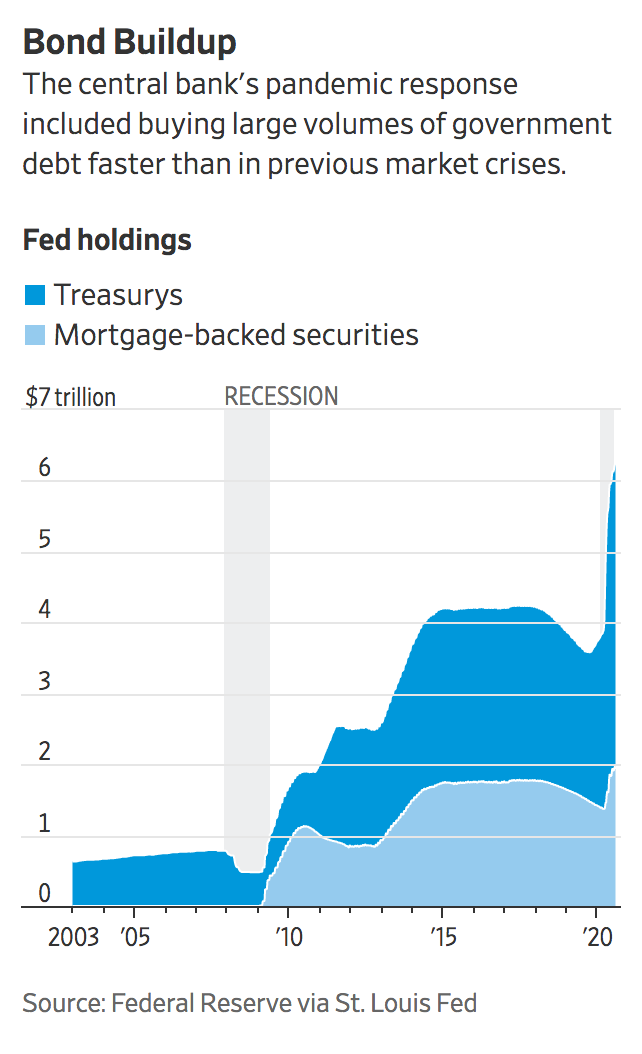

The virus shock led the Fed in March to rapidly slash short-term rates to zero, purchase trillions of dollars in government-backed debt and deploy an array of programs to backstop lending markets.

Because of the pandemic, Mr. Powell tabled discussions this spring over the framework review. The Fed resumed those discussions at their two-day meeting last week and could seek to conclude them as soon as their Sept. 15-16 meeting.

The Fed formally adopted the 2% inflation goal, a level it regards as consistent with healthy economic growth, in 2012. At the time, short-term rates also were pinned near zero. But central bankers, economists and investors still expected those rates to return to more normal levels of 4% or so once the economic expansion matured.

Even before the pandemic hit, those rates were stuck at much lower levels than 4% for reasons that weren’t expected to change soon, such as demographics, globalization, technology and other forces that have held down inflation.

The Fed justified pre-emptive rate increases because monetary policy works with a lag. “Now, you’re saying, ‘Yes, there may be lags behind, but we’re OK with an inflation overshoot because inflation has run so much below,’” said Priya Misra, an interest-rate strategist at TD Securities.

The Fed says its current 2% inflation target is symmetric, meaning officials are as uncomfortable with inflation somewhat below as somewhat above that level. In other words, 2% isn’t a ceiling.

In addition, the Fed under this approach is always aiming for 2%, and it doesn’t take into account previous deviations.

The problem for some officials is that the results haven’t been symmetric; inflation has run at or under the target, but never above it.

The Fed’s misses on inflation over the past five years were relatively small. But some officials were concerned because if the Fed can’t meet its target after a long time, consumers and businesses could expect even lower inflation.

Such expectations can become self-fulfilling, and officials would be alarmed if they were falling because of the important role expectations play in determining actual prices

In speeches over the past year, Fed governor Lael Brainard has called for shedding the current approach and taking up a way to make up for past misses of the target.

Last month, Ms. Brainard approvingly cited research that would have the Fed refrain from raising rates until inflation reached 2%, rather than initiating rate increases before achieving the target and on the basis of a forecast of higher inflation, as the Fed did in 2015.

Any changes the Fed makes would coincide with a deeper emphasis on the benefits of very low levels of unemployment. For years, officials were concerned that allowing unemployment to fall too low could generate undesirable levels of inflation, which occurred after the 1960s.

In the most recent expansion, however, officials were surprised to find unemployment falling to levels associated with higher prices, but without the anticipated inflation.

By raising rates based on a forecast of higher inflation, the Fed risks short-circuiting a labor-market expansion when many of the most disadvantaged workers are finally getting jobs or raises.

That can be costly if inflation doesn’t materialize, said Atlanta Fed President Raphael Bostic on Twitter last month.

“This isn’t inflation for inflation’s sake,” said Mr. Bostic.

The changes under consideration “would be very meaningful because it would be memorializing their commitment to working toward a tighter labor market when the economic circumstances allow for it,” said Rep. Denny Heck (D., Wash.), who is on the House Financial Services Committee. “It would be a huge break from the past.”

Updated: 8-3-2020

BlockTower’s CIO Predicts Hyperinflation Could Send Bitcoin Parabolic

Ari Paul, CIO at BlockTower Capital crypto hedge fund, believes Bitcoin’s next parabolic move will soon be triggered by hyperinflation caused by central banks’ monetary policies.

Ari Paul, CIO and co-founder at crypto hedge fund BlockTower Capital, believes Bitcoin’s next parabolic move will soon be triggered by hyperinflation caused by the monetary policies of central banks.

According to Paul, the Federal Reserve will eventually need to devalue the dollar as a means to pay its increasingly high sovereign debt.

In that scenario, according to Paul, we’ll enter a period of hyperinflation similar to the Great Inflation in the 1970s. During such an event, investors could move their wealth away from dollars and Treasury bonds and into inflation-resistance assets.

“If we have a return to something like the 1970s, I think probably gold rallies five to 10X or more, I think Bitcoin probably rallies 10 to 30X or more”, he claimed.

Paul believes this process has already started and that we are already in an “inflationary market, a Bitcoin bull market and gold bull market in the early stages”.

He also said “Bitcoin is like a call on inflation,” meaning that as long as the expectation of high inflation remains high, the price of the call (Bitcoin) will also increase.

Updated: 8-4-2020

Global Recession Supercharges Federal Reserve As Backup Lender To The World

When the coronavirus halted the global economy, the U.S. central bank lent massively to foreign counterparts.

When the coronavirus brought the world economy to a halt in March, it fell to the U.S. Federal Reserve to keep the wheels of finance turning for businesses across America.

And when funds stopped flowing to many banks and companies outside America’s borders—from Japanese lenders making bets on U.S. corporate debt to Singapore traders needing U.S. dollars to pay for imports—the U.S. central bank stepped in again.

The Fed has long resisted becoming the world’s backup lender. But it shed reservations after the pandemic went global. During two critical mid-March weeks, it bought a record $450 billion in Treasurys from investors desperate to raise dollars.

By April, the Fed had lent another nearly half a trillion dollars to counterparts overseas, representing most of the emergency lending it had extended to fight the coronavirus at the time.

The massive commitment was among the Fed’s most significant—and least noticed—expansions of power yet. It eased a global dollar shortage, helped halt a deep market selloff and continues to support global markets today.

It established the Fed as global guarantor of dollar funding, cementing the U.S. currency’s role as the global financial system’s underpinning.

Just as the Fed expanded its role in the U.S. economy to an unprecedented degree during the 2008 financial maelstrom, it has in the coronavirus crisis expanded its power and influence globally.

“The Fed has vigorously embraced its role as a global lender of last resort in this episode,” said Nathan Sheets, a former Fed economist who was the Treasury Department’s top international deputy from 2014 to 2017 and now is chief economist at investment-advisory firm PGIM Fixed Income. “When the chips were down, U.S. authorities acted.”

The value of the dollar has tumbled in recent weeks against other currencies as investors grow more troubled about the economic outlook and difficulty containing the coronavirus.

Still, it is trading near levels recorded before the pandemic hit this year and above its long-term average on a trade-weighted basis, said Mark Sobel, a former U.S. Treasury Department official now at the Official Monetary and Financial Institutions Forum, a London-based think tank.

Concerns that short-term declines in the dollar are an omen that its standing as the global reserve currency faces a threat are “vastly overdone,” he said.

The Fed supplied most of the money abroad via “U.S. dollar liquidity swap lines.” In essence, it lends dollars for fixed periods to foreign central banks and in return takes in their local currencies at market exchange rates. At the loans’ end, the Fed swaps back the currencies at the original exchange rate and collects interest.

By stabilizing foreign dollar markets, the Fed’s actions likely avoided even greater disruptions to foreign economies and to global markets.

Those disruptions could spill back to the U.S. economy, pushing the value of the dollar higher against other currencies and damping U.S. exports—and the economy.

The risks to the Fed are minimal given that it is dealing with the most creditworthy nations and the most advanced central banks. But there are risks that investors come to expect a safety net for dollars that might lead to riskier borrowing during good times.

The Fed began deploying the swap facilities on March 15. By the end of March, it had expanded them to include 14 central banks while launching a separate program for those without swap lines to borrow dollars against their holdings of Treasurys. By May’s end, the total lent out under the programs peaked at $449 billion.

The Fed’s goal is to keep financial markets functioning, and the March events had the makings of a global panic with a resulting rush for cash.

The aim was to prevent investors from dumping Treasurys and other dollar-denominated assets such as U.S. stocks and corporate securities to raise cash, which would have driven prices of those assets even lower.

‘Constructive effect’

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell in a May 13 webcast acknowledged the Fed’s global role more explicitly than his predecessors had during the last global financial crisis.

The loans let foreign central banks supply dollars cheaply to their banking systems and stopped everyone in that chain from panic-selling assets like U.S. Treasurys to raise cash, he said: “It had a very constructive effect on calming down those markets and reducing the safety premium for owning U.S. dollars.”

Andrew Hauser, the Bank of England’s top markets official, in an early June speech said those swap lines “may be the most important part of the international financial stability safety net that few have ever heard of.”

On July 29, the Fed said it would extend the temporary programs, originally scheduled to end in September, through March 2021. “The crisis and the economic fallout from the pandemic are far from over,” Mr. Powell said, “and we’ll leave them in place until we’re confident that they’re no longer needed.”

The shift has brought little of the scrutiny the Fed saw during the 2008-2009 crisis. When Mr. Powell appeared before Congress for hearings in June, lawmakers didn’t ask a single question about the huge sums the central bank made available to borrowers abroad.

The Fed’s governing charter from Congress gives it the authority to operate the swap lines, which it has done in some form since 1962, when the Fed heavily debated whether it had the authority to conduct foreign-exchange operations. Congress could revoke these authorities if it didn’t approve of how the Fed was using them.

The swaps are structured so that the Fed’s foreign counterparts bear the risk of loans going bad or currency markets moving the wrong way. A large portion of the Fed’s overseas loans have recently been swapped back as markets around the world have recovered.

The Fed’s aggressive overseas lending has injected it into the world of foreign policy: Not every country gets equal access to the Fed’s dollars.

Turkey, for example, has appealed unsuccessfully for dollar loans from the Fed to support its sinking currency, according to public comments made in April by the U.S. ambassador to Turkey, David Satterfield. A representative for the Turkish central bank didn’t respond to a request for comment.

Those decisions are based on creditworthiness, but political considerations could pose a threat to the Fed’s independence, said Mr. Sheets, the former Fed economist.

When the Fed rolled out the lending program during the 2008 financial crisis, central-bank officials consulted with the leadership of the Treasury and State Department to make sure any operations were consistent with broader U.S. objectives, he said.

“The Fed was keenly aware of this tension that, yes, this was monetary policy, but it was abutting some broader issues that were not typically the Fed’s area,” said Mr. Sheets. Concerns that such lending programs could suck the Fed into broader foreign policy entanglements were a “meaningful constraint” on the expansion of the swap lines, he said.

The moves have also left the world ever more tied to a single country’s economic management and central bank. Efforts have persisted for years to dilute the dollar’s central role, via the euro, then the Chinese yuan.

But knowing the Fed is willing to step in has led banks, businesses and investors to flock to the U.S. currency.

This gives the U.S. enormous power—to punish foreign banks for violations of U.S. sanctions, for instance, or to consider options like breaking the Hong Kong dollar’s peg to the dollar, something U.S. officials considered earlier in July, The Wall Street Journal reported, to punish China for its treatment of the city, before shelving the idea.

It also has produced a familiar cycle, said Stephen Jen, chief executive of Eurizon SLJ Capital Ltd. in London and a longtime currency analyst and money manager.

Investors value the dollar for its safety. But every time there is a major market stress there is a run to the currency, leading to breakdowns in the market, which forces the Fed to step in, which reinforces investors’ faith in the dollar, he said. “People have become more dependent on the dollar than any other currency,” he added.

The Fed pioneered the current version of central-bank swap lines in 2007, when rising U.S. subprime-mortgage delinquencies jolted short-term debt markets and made it hard for big European banks to borrow dollars.

Initially, the Fed lent to some European banks’ U.S. subsidiaries. It later rolled out swap lines to two foreign central banks, allowing the Fed to lend dollars with less risk, and expanded them to a dozen others over 2008 and 2009.

The Fed activated some of the swaps again in 2010 and 2011, as Eurozone debt problems mounted, and set up standing facilities with five major central banks in 2013.

One Fed bank president formally objected, saying that the swaps effectively let European banks borrow at lower rates than U.S. banks and that they were an inappropriate incursion into fiscal policy.

When coronavirus shutdowns hit the U.S. and Europe in March, oil prices plunged and stocks plummeted. Companies drew down bank credit lines, socking away dollars to pay workers and bills as revenue vanished. Financial markets showed alarming signs of dollar demand.

March 16, among the worst days in recent market history, brought the financial system to the brink. Stock prices plunged globally as investors scrambled to raise cash.

Banks sharply increased the cost of lending dollars to each other. Foreign banks were forced to pay dearly, gumming up the flow of dollars to their customers.

In South Korea, big brokerages suddenly found themselves in need of large sums of dollars to meet margin calls, according to Tae Jong Ok, a Moody’s Investors Service analyst who covers financial institutions in the country.

They had previously borrowed money to buy billions of dollars of derivatives tied to stocks in the U.S., Europe and Hong Kong. When those stocks plunged, lenders demanded they put up more cash.

The scramble for dollars helped push the Korean won to its lowest level in a decade on March 19.

Japanese banks suffered, too. Many had made loans directly to U.S. borrowers. The sector also owned more than $100 billion of collateralized loan obligations—bonds backed by bundles of loans to low-rated U.S. companies—that in some cases had been bought on short-term credit and needed to be regularly refinanced.

Insurers in Japan that had invested heavily in higher-yielding assets abroad also had difficulty securing dollars to fund their trades.

Indiscriminate Selling

In Singapore, high borrowing costs affected the dollar supply to companies needing to pay off debt or import and export goods, according to bankers in the city-state. “There was a classic ‘dash for cash’ scenario,” said a representative of the Monetary Authority of Singapore, adding that dollar-market conditions became so strained there was indiscriminate asset-selling.

Central bankers from Singapore, South Korea, Australia and elsewhere swapped tales of the carnage on a regular call that included a representative of the Fed, according to people familiar with the calls.

As the crisis snowballed, the Fed increased purchases of Treasurys from $40 billion a day on March 16 to a record $75 billion days later.

It also expanded the dollar swap lines to nine other countries. By March 31, the Fed had launched a new program that let some 170 central banks borrow dollars against their holdings of U.S. Treasurys.

The rollout was faster and broader than when the Fed tentatively introduced the swap lines during the financial crisis a decade earlier. Back then, “it was improvisation,” said Adam Tooze, a Columbia University history professor who writes about financial crises and war. “Today, it seems extremely deliberate.”

As financial markets recovered, dollar borrowing costs for many banks and companies outside the U.S. fell. The Fed’s outstanding currency swaps started receding in mid-June, as a wave of transactions matured and weren’t renewed, and fell further to $107.2 billion as of July 30.

The facility that lets central banks borrow against Treasury holdings hasn’t seen much use. Analysts said its presence alone helped stop the scramble for dollars.

While the Fed’s actions during the financial crisis sparked outrage—seen to be aiding firms that caused the crisis—there have been no concerns raised publicly by U.S. lawmakers or Fed officials about the Fed’s growing global role. “The whole pandemic is a different enemy,” said William Dudley, New York Fed president from 2009 to 2018. “The political support for the Fed to be aggressive is much broader this time.”

The Fed has had little choice but to intervene, given the dollar’s global centrality. Some 88% of the $6.6 trillion in currency trades that take place on average daily involve dollars, according to the Bank for International Settlements, or BIS. The dollar is also the most commonly used currency in cross-border-trade in commodities and other goods.

In addition, low American bond yields over the past decade prompted many big investors to send dollars to emerging markets. By the end of 2019, the volume of U.S. dollar-denominated international debt securities and cross-border loans reached $22.6 trillion, up from $16.5 trillion a decade earlier, according to BIS data.

Discontent about the dollar’s growing dominance has percolated for years, including among U.S. allies. Mark Carney, the Bank of England’s governor at the time, took aim at the dollar’s “destabilizing” role last August in a keynote speech at an annual central-bankers gathering in Jackson Hole, Wyo.

He argued the dollar’s growing role in international trade was out of step with America’s declining share of global output and exposed developing countries to damage from changes in U.S. economic conditions. He also outlined a proposal for central banks to create their own reserve currency.

The Trump administration’s use of tariffs and sanctions has spurred more countries to seek trading arrangements that bypass the dollar, but the efforts have had little effect.

One irony of the U.S. financial crisis was that the dollar’s use overseas only increased in its aftermath. One reason was the Fed: Its liberal lending during the crisis convinced investors that whatever happened, their access to dollars was more or less assured.

A decade ago, Jonathan Kirshner, a Boston College political science and international studies professor, predicted a decline in the dollar’s international role.

Its performance has been more robust than he anticipated, he said in a recent interview: “In the absence of viable alternatives, the dollar endures as the most important currency for the world.”

Updated: 8-15-2020

Why Cryptocurrency Is More Than A Hedge Against US Dollar Inflation

Precious metals used to be the best way to protect your portfolio from natural value deterioration, but Bitcoin is changing the game.

During times of international economic crisis, governments print money. This leads to inflation and investors subsequently stashing their investment capital in long-term, stable investments.

Historically, that has meant gold, but in the current economic crisis, gold has been joined by another long-term store of value: Bitcoin (BTC).

There are several good reasons for this. The United States Federal Reserve is handling the crisis terribly, and has responded to soaring unemployment numbers in the same way they always do: by printing money.

Already, the dollar has lost 5% of its value, with predictions that this is only the beginning. The currency is expected to shed up to 20% in the next few years, according to analysts at Goldman.

Alongside this devaluation has come another threat to investors: deflation. With the value of dollar assets dropping rapidly and the worst yet to come, investors are looking to Bitcoin as a hedge against deflation.

This appears to be the primary reason why Bitcoin has retained its value despite woeful news in other parts of the economy.

Are these investors correct, though? Can cryptocurrency act as a hedge against the dollar’s inflation? Let’s dive into it.

Inflation And Deflation

For crypto investors accustomed to dealing with daily — or even hourly — market movements, it can sometimes be easy to forget about the macro-level trends that drive our economy.

Inflation is one of these, and it’s useful to have a broad definition of the term before we look specifically at the role of crypto in beating it.

Essentially (and as you might remember from Economics 101), inflation generally comes about because of a general decrease in the purchasing power of fiat money.

Many things can cause this loss of purchasing power: foreign investors pouring out of a particular currency, or even investors attacking a currency.

Most often, though, inflation is the result of an increase in money supply, like when the Fed unilaterally creates billions of dollars and sends out checks to millions of Americans, for instance.

Deflation is the opposite. In deflationary scenarios, prices decrease as fiat currency increases in value relative to different goods and services. Again, there can be different causes for this, but it generally comes about due to tightly controlled fiscal policies, or technological innovation.

The Global Pandemic And Inflation

The key point in these definitions is that inflation can only occur in fiat currencies — i.e., those not based on the market value of a tangible asset, but largely on confidence in growing gross domestic product.

Since the Bretton Woods agreement of 1944, the latter has been the basis of the U.S. dollar’s value.

Having a fiat currency gives governments a powerful degree of freedom when it comes to printing money, and supposedly when it comes to controlling inflation.

However, when confidence in the government is low (as it is now), government spending programs can lead to inflation quickly getting out of control. In the 1970s, gold boomed because investors saw it as a hedge against the dollar’s rapid inflation.

This is similar to what is happening now. The global COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to a massively inflationary monetary policy and aggressive expansion of money supply while prices in certain key areas such as food staples keep increasing due to supply shocks caused by lockdowns.

In this environment, it’s no surprise that gold is booming. There is, after all, only a limited supply of gold on earth, and so its price cannot easily be affected by government policy. Some crypto currencies, however, are also booming — apparently for the same reason. Billionaire investors are therefore lining up to compare Bitcoin to gold.

Bitcoin: A Deflationary Asset?

The reason why some forms of cryptocurrency can act as a hedge against inflation is precisely the same reason gold can: there is a limited supply. This is something that is often forgotten about by many, even those in the crypto space, but it’s worth remembering that many cryptocurrencies — and most notably, Bitcoin — are built with an inherent limit.

The 21 million Bitcoin limit means that at a certain point, there should be fewer Bitcoins versus the demand for them, meaning that in terms of value, the price per unit should increase as the supply decreases.

In addition, the fact that Bitcoin allows investors to limit their exposure to government surveillance networks means that, in this time of low confidence in government, many people are moving their investments away from the U.S. dollar and toward crypto in order to avoid inflation and government tomfoolery. In other words, the comparison with gold investments of previous crises seems pretty apt.

But here’s the thing: It’s not completely clear that Bitcoin is, in fact, a deflationary asset. Or at least, not yet. While it is technically true that the supply of the currency is limited, we are nowhere near that limit, with most estimates putting the last Bitcoin to be mined in 2140.

What this means, in practice, is that Bitcoin will be unable to act as a completely stable hedge against inflation for at least another 120 years.

Flexibility And Stability

This might not matter that much, of course. One of the primary driving forces behind the rise of Bitcoin has been the combination of (relative) stability and (relative) variability that it affords.

In this context, it’s heartening that investors now regard crypto as a stable hedge against an inflating U.S. dollar, but to regard crypto as merely a replacement for gold would be to miss the point: Cryptocurrency is far more than just a hedge.

Updated: 8-16-2020

It’s Time To Build Cash To Take Advantage of Stocks’ Coming Tumble

Summertime, and the livin’ is uneasy. Stocks are jumpin’ and the market is high. So, hush, all you skeptics, don’t you whine.

With apologies to the Gershwins and DuBose Heyward, this mangling of the lyrics of “Summertime” from Porgy and Bess seems appropriate, as the stock market’s benchmark, the S&P 500 index, is on the verge of reclaiming its record peak in this summer of our disquiet, if not discontent.

Stock market highs are associated with upbeat songs, such as Irving Berlin’s “Blue Skies,” to cite another tune from that bygone era. “Never saw the sun shining so bright, never saw things going so right,” went this popular 1929 ditty.

With the S&P 500 ending the week a fraction of a percent below its Feb. 19 high close of 3386.17, the disparity between the equity market and the real economy, which is struggling to cope with the coronavirus pandemic, remains stark.

As a measure of how far we’ve come, Thursday marked the 100th day since the S&P 500’s low of March 23, writes Ryan Detrick, chief market strategist of LPL Financial, in a research note.

The 50%-plus rebound since then marks the best 100-day gain for the big-cap benchmark, “while millions of people have lost their jobs and tragically more than 160,000 Americans have lost their lives,” he adds.

In the past, large 100-day rallies usually were followed by continued gains, with stocks higher a year later in 17 out of 18 instances, Detrick adds. But other market observers see more risk than reward as the S&P 500 approaches its previous highs.

Sentiment is nothing if not frothy. That’s evident in the “very vigorous public participation” in the market, remarks Julian Emanuel, chief equity and derivatives strategist for BTIG.

More than the massive rise in the “FAAGM” megacap tech names, froth was evident in the bidding up of recent stock splits, which made even less sense than the rush into bankruptcy stocks. (For more on splits, read this.)

Given the availability of fractional shares on many online brokers’ platforms, the positive impact of splits on high-profile stocks, such as Apple (ticker: AAPL) and Tesla (TSLA), is further evidence of irrational exuberance that recalls the frenzy of the dot-com bubble at the turn of the 21st century.

More important, the disconnect between the stock market and underlying fundamentals is unequivocally the greatest in the past 30 years, Emanuel says in a telephone interview.

There are other disconnects, too. A seemingly small example: To a football fan, it didn’t seem coincidental that the market rolled over when the Big Ten said that it would cancel the fall season, he notes.

Indeed, the S&P 500’s valuation at 26 times expected earnings, at the same time that the economy confronts the clear and present danger of a relapse, makes for a significant headwind to the stock market, Emanuel continues.

That’s even before considering the political season ahead, in which the invective will only get nastier, and continued wrangling over much-needed relief for households will persist.

Then there’s the inexplicable but persistent tendency of the stock market to get battered in September, in the middle of the Northern Hemisphere’s hurricane season.

The key question for investors to ask themselves is how they would react in the event of a typical 10% to 15% correction, Emanuel says. Such a setback should be far from surprising, given the current state of the market and the underlying fundamentals. But it wouldn’t be the start of a new bear market, he emphasizes.

If you aren’t prepared to put more money to work in the market during such a drawdown, you own too many stocks now, he pointedly advises. He suggests taking some chips off the table to raise cash, and rotating out of the huge winners into laggard sectors, such as energy and financials, as well as health-care stocks.

What seems apparent is that investors have embraced the view of Dr. Pangloss, who famously asserted in Voltaire’s Candide that this is the best of all possible worlds, writes James Montier of GMO, the institutional money manager, in a client note.

Voltaire also wrote, “Doubt is not a pleasant condition, but certainty is absurd,” an observation that Montier says applies to the U.S. stock market.

Updated: 8-18-2020

Suddenly, It’s Not Just Bitcoiners Who Think the Dollar’s Going Down

As the news broke in recent days that Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway had bought shares in a gold miner, commentators immediately began to wonder if the billionaire investor might be betting against the U.S. economy or the dollar.

Bitcoin analysts and investors wondered why it took him so long, given the trillions of dollars of money pumped into the financial system this year by the Federal Reserve to help fund the ballooning U.S. national debt.

“The money printer working overtime is obviously causing Buffett and his board grave concern,” Mati Greenspan, of the foreign-exchange and cryptocurrency research firm Quantum Economics, wrote Monday. “While Buffett is perhaps not so sure how to react to a world that no longer values bonds and government debt, others are sure.”

There’s a growing sense among members of the cryptocurrency community that their longstanding assessment of the traditional financial system as unsustainable is finally gaining traction among Wall Street experts and mainstream investors. If the concerns spread, it might buoy prices for bitcoin, which many digital-asset investors view as an inflation hedge similar to gold.

Goldman Sachs, which in May of this year panned bitcoin as “not a suitable investment,” hired a new head of digital assets earlier this month and acknowledged rising interest in cryptocurrencies from institutional clients. The firm warned in July that the U.S. dollar was at risk of losing its status as the world’s reserve currency.

Dick Bove, a five-decade Wall Street analyst who now works for the brokerage firm Odeon, wrote last week in a report that the U.S. dollar-ruled financial system could come to an end amid challenges from a possible multi-currency system, which include digital currencies.

“The case for bitcoin as an inflationary hedge and sound investment is being articulated with crystal clarity by influential people outside of our crypto bubble,” the digital-asset analysis firm Messari wrote last week. Buffett didn’t return a call for comment.

Dollar Dominance On The Wane?

Whether or not bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are the answer, there’s little on the horizon that might turn investors away from the gnawing sense that U.S. finances are becoming more precarious.

Goldman Sachs economists predicted in an Aug. 14 report that the Federal Reserve will pump $800 billion more into financial markets by the end of this year, followed by another $1.3 trillion in 2021.

According to Bank of America, there’s a risk investors might shift their “portfolio allocation out of U.S. dollar assets” to position for the “erosion of the hegemony of the dollar as a reserve currency.”

“A constitutional crisis is one dynamic that could potentially accelerate the process of de-dollarization,” they wrote, noting that November’s presidential election might be “fiercely divisive” and “contested.”

According to the bank, a recent survey of fixed-income money managers showed nearly half of respondents expect foreign central banks to decrease their reserve holdings of dollars and dollar-denominated assets over the next year.

It may not sound outlandish to bitcoin bulls.

Updated: 8-26-2020

Fed Chair Powell’s Jackson Hole Speech Could Hint at US Dollar’s Future

A speech by Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell scheduled for Thursday offers a reminder of just how dramatically once-slow-moving monetary forces have accelerated due to the devastating economic toll of the coronavirus pandemic.

This time last year, President Donald Trump was vehemently criticizing Powell on Twitter for setting interest rates too high, as U.S. economic growth slowed and the national debt swelled past $22 trillion.

This time last year, then-Bank of England Governor Mark Carney delivered a speech at the Fed’s annual Jackson Hole Economic Symposium in Wyoming warning the U.S. dollar’s status as the de facto global currency contributes to an unsustainable international economic and monetary regime.

He argued that world leaders should create a “synthetic hegemonic currency,” potentially provided “through a network of central bank digital currencies.”

Fast forward to now, and the Jackson Hole conference has been forced to go virtual because of the coronavirus. Trump’s economic stewardship, including a U.S. stock market that many investors now say is propped up by the Fed’s $3 trillion of freshly printed money, has become a core issue in the 2020 presidential election. The national debt now stands at $26.5 trillion.

Digital currencies are now being studied and pursued by central banks in China, the U.S. and just about everywhere else. Goldman Sachs recently warned the dollar risked losing its dominant reserve status.

“The pandemic has sped up key structural trends and triggered substantial market swings,” strategists for the $7 trillion money manager BlackRock wrote this week. “The policy revolution was needed to cushion the devastating and deflationary impact of the virus shock. In the medium term, however, the blurring of monetary and fiscal policy could bring about upside inflation risks.”

As the spread of the coronavirus earlier this year triggered lockdowns and quarantines, the global economy this year entered its deepest recession since the early 20th century.

When markets from stocks to bitcoin swooned in March, the Fed slashed interest rates close to zero and has since announced plans to buy U.S. Treasury bonds in essentially unlimited amounts while providing emergency liquidity for money markets, Wall Street dealers and corporations.

“The road ahead is highly uncertain,” Fed Governor Michelle Bowman said Thursday in a speech in Kansas.

‘No Easy Way Out’ For Powell

Many investors are betting on bitcoin as a hedge against the potential debasement of the U.S. dollar, but Fed officials say deflationary forces might be stronger because of an expected drop off in demand from consumers and households.

Analysts for Bank of America, the second-biggest U.S. bank, wrote earlier this week in a report that bond market traders expect the Fed to adopt a “major new policy framework aimed at better achieving its 2% target” for annual inflation.

As of the last reading, the central bank’s preferred measure of consumer price increases registered just 0.9%, so the baseline expectation is the Fed would let inflation rise well above 2% so that the average over a long period of time gets closer to the target.

“Let us be optimistic and say it takes three years to create some inflation,” Matt Blom, head of sales and trading at the digital-asset firm Diginex, wrote Wednesday in an email. “We would need to drive it above 3.5% and maintain it there for years before we are able to use an average calculation.”

It’s unclear what Fed scenario is already priced into the market, but Bank of America’s Athanasios Vamvakidis, a foreign-exchange analyst, wrote that there is “no easy way out” for Powell and his colleagues.

“Without inflation eventually acting as a budget constraint, we see risks for recurring and worsening bubbles, with further divergence between Wall Street and Main Street,” Vamvakidis wrote.

What Powell’s Speech Could Say About The Dollar’s Future

Crypto traders will focus in the short term on what the Fed’s speech might mean for bitcoin prices, which have surged almost 60% in 2020, far exceeding this year’s 7.7% year-to-date gain in the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index of U.S. stocks.

But the Fed’s actions could also have implications for ether, the native token of the Ethereum blockchain, where entrepreneurs are developing alternative currencies and semi-autonomous lending and trading networks that might one day replace the current financial system. There’s also a fast-growing business in dollar-linked “stablecoins,” with the amount doubling this year to $13 billion.

“So much has changed,” said Joe DiPasquale, CEO of the cryptocurrency-focused hedge fund BitBull Capital. “There is this danger of the U.S. [dollar] in the future no longer being the world’s reserve currency. We are in a much worse position than we were in a year ago.”

Mati Greenspan, founder of the cryptocurrency and foreign-exchange analysis firm Quantum Economics, wrote this week that Powell’s return to Jackson Hole comes at a time when “people are just starting to ask questions about the intrinsic value of money.”

“U.S. authorities have just taken on an inordinate amount of debt, more than they could possibly ever hope to pay back,” Greenspan wrote. “So the only viable option is to decrease the value of that debt by way of monetary debasement. It’s despicable and dangerous, but the only other option is austerity, which is too unpopular for any public servant to mention at this time.”

Updated: 8-28-2020

US Dollar Slides To Lowest Level In 2 Years As Nation Grapples With TrumponomicsFail#

* The US Dollar Index fell to its lowest level since May 2018 on Tuesday as investors grew more bearish toward the currency.

* The gauge has dropped for five days straight amid continued virus risk and fears of new stimulus arriving too late to best aid the economy.

* With short interest in the dollar booming and other countries better handling their outbreaks, the currency stands to fall further before regaining its strength.

* Watch the US Dollar Index update live here.

The greenback slid to a two-year low on Tuesday as investors grew increasingly concerned about how a stimulus deadlock could exacerbate the coronavirus’ economic scarring.

The US Dollar Index – which tracks the dollar’s value against a basket of other currencies – fell as much as 0.8% to its lowest since May 2018. The gauge has fallen for five days straight, bringing its year-to-date drop to around 4.2% as the US continues to grapple with the pandemic.

The dollar began its decline in March as the virus slammed the economy and forced widespread lockdowns. The drop worsened through the summer as premature reopenings kicked off a second wave of infections.

With legislators failing to agree on new fiscal stimulus and outbreaks continuing to cripple economic activity, the US currency stands to worsen compared to nations containing the virus.

“Longer-term, we see dollar weakness as US debt grows, and the global recovery gains momentum. Near term, dollar may strengthen with uncertainty during flu season,” Eric Bright, managing director at Bel Air Investment Advisors, said.

Investors had already been hedging the dollar’s weakness and buying gold, but institutional players are now entering the trade. Hedge funds are net short on the dollar for the first time since May 2018, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Such bearish activity could place greater downward pressure on the dollar if other nations rebound faster than the US.

The Dollar Index stood at 92.36 as of 11:50 p.m. ET Tuesday.

Updated: 8-30-2020

A Flexible Fed Means Higher Inflation

Broad thrust of central bank’s new strategy is that it will be even more dovish, and interest rates will stay low for even longer

The Federal Reserve has just given itself a license to do pretty much whatever it wants.

Chairman Jerome Powell will no doubt disagree: His speech on Thursday set out a new target for average inflation of 2%. But because he ruled out any mathematical definition of the average, anything from serious deflation up to inflation of 3.2% over the next five years could count as success.

This isn’t really a problem. The broad thrust of the Fed’s new strategy is that it will be even more dovish, and interest rates will stay low for even longer. But—and it is a vital point—what the Fed is really saying is that we should trust that it won’t let inflation spiral out of control, so any overshoots of 2% won’t last long.

The Fed wants people to believe inflation will be roughly 2% in the long run, and more precision than that isn’t really necessary.

Those who prefer their monetary policy to be governed by rules will be disappointed. The Fed used to let bygones be bygones, ignoring what had happened to inflation in the past as it pursued its goal of 2% in future.

A catch-up strategy means that the failure to hit 2% for most of the past decade could be used to justify inflation above 2% for most of the next decade. The lack of a firm rule, though, means Mr. Powell isn’t tied to having to compensate for any future period above 2% by running below that for a while afterward.

Mr. Powell says the new approach is flexible. He isn’t kidding. Choose your period, and almost anything can be justified. Since 1960, inflation has averaged 3.2% (using the mathematically correct geometric, or compound, average of the Fed’s preferred inflation measure).

A hawk applying a strict policy of inflation averaging could justify aiming for deflation for years to bring the long-term average back down to 2%. Some bygones will still be ignored.

The same mathematical problem bedevils what might appear to be more reasonable approaches. Should the average apply since the Fed adopted its target in 2012? Since Mr. Powell took over in 2018? Since five years ago?

There is no correct answer, and the results are different enough to be significant for policy: Start from 2012, and the next five years need inflation of 3.2% to bring the average up to the goal.

Start from Mr. Powell’s appointment, and it needs to be 2.3%, while starting five years ago would require inflation of 2.5%.

Rather than get lost in the math, the Fed’s new policy is just saying that the central bank will be really dovish for a really long time. The dovishness is backed up by a shift on unemployment, too, where low numbers of jobless will no longer prompt pre-emptive action to head off inflation.

Investors heard him, and responded appropriately. Long-dated bond yields jumped as they usually do when rates are cut, as the Fed was no longer expected to choke off a recovery so soon.

It is easy to argue that all this is irrelevant. The Fed is stuck with zero rates, has ruled out going negative and has been slow to set explicit targets for bond yields, something known as yield-curve control. With its inflation measure at just 1% last month, there is little need to worry about what will happen at 2% now.

But it matters for markets, and so for the economy. Thursday’s markets did exactly what Mr. Powell must have been hoping: higher long-dated Treasury yields, but also higher stock prices—with the biggest losers this year turned into winners, and vice versa.

Out of Thursday’s top 100 performers in the S&P 500, all but six had lagged behind the index this year, with the majority falling by double-digit percentages. The reflation trade was back, and showed that investors think the Fed still has power.

Quite how that power will be used is less clear than it was. The new policy means the Fed can more easily justify higher inflation, and surely will. But where it will draw the line remains uncertain. If and when inflation picks up again, working out what “flexible” means will be critical for investors.

Updated: 8-31-2020

Top Fed Official Says New Framework Provides More Humble Approach to Setting Rates

Changes reflect reality that economic models ‘can be and have been wrong,’ says Vice Chairman Richard Clarida.

A top Federal Reserve official said the central bank would resume discussions at its meeting in two weeks over how it could refine its guidance about plans to keep interest rates lower for longer.

Fed Vice Chairman Richard Clarida offered little specifics about what changes might be considered or when they might be unveiled, saying he didn’t want to prejudge the outcome of coming discussions. The Fed’s next policy meeting is Sept. 15-16.

Officials are turning their attention to what ways they can provide more support to the economy after cutting rates to near zero in response to the downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic in March. They are buying Treasury and mortgage securities at a rate of more than $1 trillion a year and have signaled no interest to raise rates for years.

The coming discussions on how to tweak their asset purchase program or refine their so-called forward guidance about interest rates has been smoothed by the conclusion last week of a yearlong policy revamp in which the Fed will seek periods of slightly higher inflation after periods in which price pressures run below their 2% target.

In remarks Monday, Mr. Clarida said the central bank needed to be more skeptical of models that predict higher inflation when setting interest-rate policy, given the weak response of inflation to lower levels of unemployment over the past decade.

The Fed’s new framework states that the Fed won’t raise interest rates simply because unemployment has fallen to a low level estimated to spur faster price inflation, Mr. Clarida said.

Concerns that too-low levels of unemployment would lead to a surge in inflation led the Fed to very slowly begin raising rates in 2015 after seven years in which rates were pinned near zero.

Mr. Clarida signaled a note of humility in his remarks Monday. The change “reflects the reality that economic models of maximum employment, while essential inputs to monetary policy, can be and have been wrong,” he said.

“A decision to tighten monetary policy based solely on a model without any other evidence of excessive cost-push pressure…is difficult to justify given the significant cost to the economy if the model turns out to be wrong.”

Mr. Clarida said the Fed needed to change its policy-setting framework because officials will have less room to spur growth by cutting interest rates in a world where they are pinned near zero more often.

The Fed formally adopted a 2% inflation target in 2012 but since then has encountered greater challenges boosting inflation because their main policy tool, a short-term benchmark interest rate, has been pinned near zero.

If the central bank targets 2% inflation and consistently falls short, expectations of future inflation will slide, making it much harder to achieve the target, said Mr. Clarida.

The changes adopted last week also effectively raised the Fed’s inflation target by saying the central bank should take past misses of the 2% target into account and seek periods of moderately higher inflation to compensate.

Mr. Clarida said Fed officials believed two tools—forward guidance and asset purchases, which the central bank deployed last decade—would be best suited to provide stimulus after the Fed lowered rates to zero.

Mr. Clarida reaffirmed the Fed’s lack of support to cut rates below zero and said a separate strategy of committing to purchase unlimited amounts of Treasury securities to cap yields remained an option, but one that is on the back-burner.

If forward guidance and other central bank communication is credible, caps would provide only modest benefits. “The approach brings complications in terms of implementation and communication,” said Mr. Clarida. Still, he said, the Fed believed the tool should remain an option “if circumstances change markedly.”

Mr. Clarida, who has led the Fed’s framework review initiated by Chairman Jerome Powell in late 2018, said the central bank’s rate-setting committee will turn its attention at coming policy meetings to possible refinements to other communication tools, including its statement of economic projections. The Fed will try to reach a decision on any changes by December, he said.

Updated: 9-1-2020

Bitcoin Nears $12K As Dollar Declines To 29-Month Low

Bitcoin is drawing bids amid a sell-off in the U.S dollar, with new signs emerging that the largest cryptocurrency is maturing as a global asset class.

* At the time of writing, bitcoin is trading near $11,900 – up 2% on the day. Prices reached a high of $11,964 early Tuesday, according to CoinDesk’s Bitcoin Price Index.

* The dollar index, which gauges the greenback’s value against major currencies, is currently trading 0.4% lower at 91.75, the lowest level since April 2018. The greenback is down more than 10% from highs seen in Mach.

* “From a macro level, the U.S. dollar has continued to fall since [the Federal Reserve’s Jackson Hole meeting], creating a further buying pressure on bitcoin and broader safe-haven commodities such as gold,” Matthew Dibb, co-founder of Stack, a provider of cryptocurrency trackers and index funds, told CoinDesk in a WhatsApp chat.

* Investors are selling dollars, possibly on bets that interest rates in the U.S. would remain low for a long time.

* The Federal Reserve now has the room to hold rates low for a prolonged period, having signaled tolerance for high inflation last week.

* U.S. inflation expectations have continued to strengthen since Fed Chair Jerome Powell’s inflation speech at Jackson Hole last week.

* The 10-year breakeven inflation rate, or the bond market’s expectation of price pressures over the next ten years, rose to 1.8% on Monday, the highest level since Jan. 2, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

* Long-term inflation expectations have more than tripled in the past 5.5 months to 1.8%.

* Additional bullish pressure for bitcoin may be stemming from ether’s rise to two-year highs near $470.

* “Bitcoin is showing significant strength today on the back of recent gains in ethereum and the broader alternative cryptocurrencies,” Dibb said, citing increased buying in the $12,000 call option expiring in September as evidence of the market’s short-term bullish mood.

* The Singapore-based QCP Capital noted in its Telegram channel that “there was a flurry of put buying on Monday and more of such hedging flows may be seen in the next weeks if bitcon is held below $12,500.”

Updated: 9-1-2020

Jerome Powell Throws Us Dollar Under A Bus In Jackson Hole

Fed Chairman Jerome Powell threw the U.S. dollar under a bus last week at the central bank’s annual Jackson Hole, Wyoming, meeting.

The Economic Policy Symposium hosted annually by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City — an event attended by finance ministers, central bank managers and academics, among others — was held virtually due to COVID-19 concerns this year, and there was little virtual about the announcement. The U.S. dollar would be fed to the wolves.

A Monumental Shift From An Already-Unprecedented Monetary Policy Stance

To be sure, the Fed has persisted with an accommodative monetary policy posture since the Great Recession despite strong years of growth in the middle of the Obama years and sluggish yet consistently positive growth the rest of the time.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, the Fed had begun raising interest rates beyond the zero range, as the need to leave something in the tank should another crisis ensue was acknowledged.

Those moves were roughly in line with growing central banker concerns globally that accommodative monetary policy had failed to generate robust growth rates and risked making central bankers toothless in case a serious recession occur.

What has been little understood through the last two decades is that with Chinese imports raging throughout western markets, deflationary forces were being bought inbound at the same time as labor demand faced unprecedented challenges.

The global economic structure was changing.

Nevertheless, central banks around the world persisted in their efforts to inflate economies and encourage growth — not that there was no growth. In fact, when Powell took over the reins in 2018, the United States was enjoying the longest period of economic expansion in its history. But the growth was sluggish.

Changing Course Just At The Wrong Time

The Federal Reserve had raised rates nine times between 2015 and 2018, with prices stagnating every time it did. That change in direction, however, was soon to be turned on its head courtesy of a 100-year pandemic.

Since the COVID-19 onslaught, the Fed and its counterpart banks slashed rates back down to zero-bound levels, as economies were brought to a standstill. In March, the Fed announced a policy of being prepared to purchase an unlimited amount of treasuries and mortgage-backed securities to shore up financial markets.

Its balance sheet ballooned by over $3 trillion to around $7 trillion with no end in sight. And last week, Powell revealed a much-anticipated stance of “average inflation targeting.” Since 1977, the Fed’s dual mandate has been to maintain maximum employment and stable prices. The latter is considered a 2% inflation rate.

All that changed last Thursday. By targeting average inflation, Powell indicated that the Fed would keep interest rates lower than they needed to be, notwithstanding the health of the economy to push prevailing inflation above 2% if inflation had previously run lower than that for too long.

In today’s context, the picture is frightening. Inflation has run just significantly shy of 2% since the Great Recession. To drag that average up to the target rate retrospectively, Powell and colleagues may be set to target levels around 3% for a prolonged period of time.

What Average Inflation Targeting Could Mean For The Dollar

If the Fed maintains an accommodative monetary posture well into a broader economic recovery, the results will almost undoubtedly be asset bubbles in stocks and housing.

That is exactly what happened following the recovery from the Great Recession. In fact, stocks have already proven buoyant since the coronavirus shutdowns, with investors ensured continued asset price support from regulators.

The Wall Street maxim “never bet against the Fed” has never been truer. Wealthy investors, always the first in line for cheap money, stand to gain the most from low-interest rates. The impact of that is bubbles in valued assets like housing that price ordinary homeowners out of the market.

Another obvious peril for the economy is the debasement of the currency. Already, investors and corporations have seen the writing on the wall. MicroStrategy, a publicly-traded business intelligence company, recently swapped its U.S. dollar cash reserves for Bitcoin (BTC) to avoid a balance sheet loss that would result from a falling dollar.

The Winklevoss twins argue that inflation is inevitable. While gold, oil and the U.S. dollar have long been the go-to safe-haven assets, gold and oil are illiquid and difficult to store, and the U.S. dollar is no longer safe as a store of value. They see Bitcoin benefiting enormously from the Fed’s actions.

Don Guo, The Ceo Of Broctagon Fintech Group, Pointed Out:

“Should inflation continue to run high, we can expect many investors to use Bitcoin as a hedge, propelling its price up further. Throughout 2020, numerous analysts have predicted Bitcoin to reach heights that are unheard of, and it is undeniable that the market is in an even stronger position than it was during its 2017 bull run. Since then, the market has matured greatly, with increased institutional involvement and media popularity as a result.”

If inflation appears inevitable to the Winklevoss twins, the Fed has all but guaranteed it. Grayscale recently released a report, arguing:

“Fiat currencies are at risk of debasement, government bonds reflect low or negative real yields, and delivery issues highlight gold’s antiquated role as a safe haven. There are limited options to hedge in an environment characterized by uncertainty.”

Fixed supply assets such as Bitcoin appear primed to triumph from Jerome Powell’s latest set of announcements. As the dollar suffers the fate of significant value debasement at the hands of regulatory overkill, Bitcoin is sure to emerge as a winner.

Updated: 10-14-2020

22% Of All Us Dollars Were Printed In 2020

$9 Trillion in Stimulus Injections: The Fed’s 2020 Pump Eclipses Two Centuries of USD Creation.

Since September 2019, research shows the Federal Reserve has pumped over $9 trillion to primary dealers by leveraging enormous emergency repo operations. A recently published investigative report shows the U.S. central bank submits the daily loan tally, but the Fed will not provide the public with information concerning the recipients. Estimates say, in 2020 alone, the U.S. has created 22% of all the USD issued since the birth of the nation.

The U.S. Federal Reserve has printed massive amounts of funds in 2020 and bailed out Wall Street’s special interests during the last seven months. On October 3, 2020, Redditors from the subreddit r/btc shared a video called “Is Hyperinflation Coming?” and discussed how the U.S. central bank has created 22% of all the USD ever printed this year alone.

“The U.S. dollar has been around for over 200 years and for the bulk of that time, it was backed by gold,” one Reddit user wrote on Saturday. He added:

Having a quarter of all USD printed in a single year is more than alarming, it’s mind-blowing.

Additionally, on October 1, 2020, Wall Street on Parade’s (WSP) Pam Martens and Russ Martens published a comprehensive report on how the U.S. central bank pumped out “more than $9 trillion in bailouts since September.” The findings show that the Fed is also getting market advice from Wall Street hedge funds like Frontpoint. The hedge fund Frontpoint Partners is a controversial firm because it shorted the subprime mortgage market during the 2007 to 2010 financial crisis.

The latest WSP analysis shows that the Fed has been “conducting meetings with hedge funds” like Frontpoint in order to get the financial institution’s “input on the markets.” In 2007 to 2010, the Fed was leading a group of lending facilities and once again the central bank is working with three major emergency lending facilities: the Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility; the Primary Dealer Credit Facility; and the Commercial Paper Funding Facility.

“On top of those facilities, beginning on September 17, 2019 – months before the first case of Covid-19 was reported in the United States – the New York Fed embarked on a massive emergency repo loan operation, which had reached $6 trillion cumulatively in loans by January 6,” the WSP findings detail. The Martens’ also state:

The Fed has provided data on the total amounts of the daily loans, but not the names of the recipients. All it will say is that the loans are going to its 24 primary dealers, which are the trading units of the big banks on Wall Street. The last time we tallied its data in March, it had sluiced over $9 trillion cumulatively to these trading houses.

A number of people believe that the massive creation of money stemming from the Fed will eventually cause hyperinflation. The dollar has lost considerable value since the introduction of the central bank in 1913. For instance, the cumulative rate of inflation since 1913 is around 2,525.4%. This means a product purchased for $1 in 1913 would cost $26.25 in October 2020.

Precious metals and cryptocurrency proponents believe the central bank’s pumping will bolster assets like bitcoin and gold. Pantera Capital CEO Dan Morehead explained in July that the company believes cryptocurrencies like bitcoin (BTC) will help people with the gloomy economic outcome.

“The United States printed more money in June than in the first two centuries after its founding,” Morehead wrote in a letter to investors. “Last month the U.S. budget deficit — $864 billion — was larger than the total debt incurred from 1776 through the end of 1979.”

On the same day Pantera Capital published the letter called “Two Centuries Of Debt In One Month,” the 22-year congressional veteran, Ron Paul, told the public that Americans should be “prepared.”

Paul has exposed the U.S. Federal Reserve for the last two decades and has written extensively about the central bank’s fraud. In the video, the former congressional leader said the medical community, U.S. bureaucrats, and the Fed have done things he never expected.

“After so many years in Washington, I thought I was immune to being shocked by what our government does,” Paul detailed. “But the actions that our elected officials… the Fed… even the medical community have taken in the past few weeks have gone beyond anything I could have imagined.”

“Most Americans will be blindsided by what’s going to happen. Make sure you, your family, and anyone you care about are prepared,” the former U.S. Presidential candidate insisted.

Meanwhile, the U.S. airline industry is looking for a second bailout, three days ago the number of the country’s mortgages involved in the bailout program spiked by 21,000, the hotel industry is looking for stimulus, and President Trump recently revealed a multi-billion dollar farm bailout.

Updated: 10-25-2020

A Weakening U.S. Dollar Is Still The Preeminent Currency

The greenback has depreciated 11% from its March peak, but it has a long way to go before it gives up its reserve status.

In early June, the U.S. dollar appeared to be in total free fall. From May 14 through June 8, the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index tumbled 4.6%, effectively wiping out all of its appreciation during the worst of the coronavirus crisis.

A Bloomberg Opinion column from Stephen Roach, former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia, declared: “A Crash in the Dollar Is Coming.” He got a lot of pushback.

Depending on how you define a “crash,” it certainly looks as if the Yale University faculty member had the direction right. The Bloomberg dollar index is down an additional 3.7% since then, well below its moving averages and dangerously close to breaking through a key intraday level that could give traders scope to push it lower by at least 2% more.

The four-year chart, which captures the ups and downs of the foreign-exchange market since President Donald Trump was elected, looks rather ominous.

Yet when evaluating the dollar on a 10-year time horizon, the greenback’s move over the past several months looks less like a crash and more like a simple unwind of the haven flows during the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, combined with a natural weakening given the Federal Reserve’s relatively more aggressive monetary policy response compared with its global central bank peers.

When thinking about the fate of the U.S. dollar, it’s crucial to separate an extended decline in the greenback’s exchange rate from the prospect of America losing its place as issuer of the world’s primary reserve currency.

These are distinct outcomes with drastically different implications. The former is hardly unusual, given that the dollar has historically fluctuated in multiyear cycles since the early 1970s. The latter would represent a seismic shift in the structure of the global financial system.

Simply put, it’s in no country’s or region’s best interest (at least not imminently) for the U.S. dollar lose its place as the reserve currency of choice.

That means the dollar will retain its place on the global stage no matter how weak it might get in the months to come. But make no mistake: There are any number of reasons to bet that the greenback will slide further.

Most obviously, the dollar tends to appreciate when U.S. interest rates climb and weaken when they fall. Short-term Treasury yields are pinned near zero and are expected to stay there for years, while longer-term yields have increased somewhat but remain near all-time lows.

There’s also the well-known fact that the federal budget deficit has ballooned this year in response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Traders widely expect that large shortfalls will continue in the year ahead, particularly if the Democratic Party sweeps the White House and both chambers of Congress, as polls indicate.

Either way, America’s so-called twin deficits — in both its current account and budget — are so extreme that a regression analysis from Bloomberg News’s Cameron Crise projects a 31% decline over the next two years in the ICE U.S. Dollar Index, known as DXY. There’d certainly be no hyperbole in calling that a “crash.”

It’s hard to imagine that sort of precipitous decline happening, however, without an exogenous shock that’s separate and distinct from interest rates and deficits. My Bloomberg Opinion colleague Noah Smith posited last month that a complete breakdown in America’s institutions could be that force:

Urban chaos, violent conflict and uncertainty over who will control the country in the coming years make for a very bad business environment. In a worst-case scenario, businesses and investors could decide the U.S. is a failing state and that their money is best kept elsewhere, at least until things quiet down.

The result could be an unprecedented capital flight — money stampeding out of one of the world’s largest economies and abandoning the reserve currency at the same time. That would probably mean a dollar crash, a surge of U.S. inflation and destabilizing flows of hot money into Europe, Japan, Canada, Australia, South Korea and other, more stable developed nations.

Suffice it to say, that sort of dystopian outlook probably shouldn’t be anyone’s base-case scenario for how the next few months will unfold in the foreign-exchange market.

Indeed, speculative U.S. dollar traders recently turned positive on the greenback for the first time in four months, with net noncommercial positions in DXY futures rising above zero for the first time since June, according to Commodity Futures Trading Commission data.

While that’s hardly a decidedly bullish position, it at least suggests a sizable pool of money will take the other side of the dollar doomsday narrative.