Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts For Short-Term Rental Market (#GotBitcoin?)

Amateur hosts dominate the industry, but big hotel companies and some well-funded startups are out to change that. Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts For Short-Term Rental Market (#GotBitcoin?)

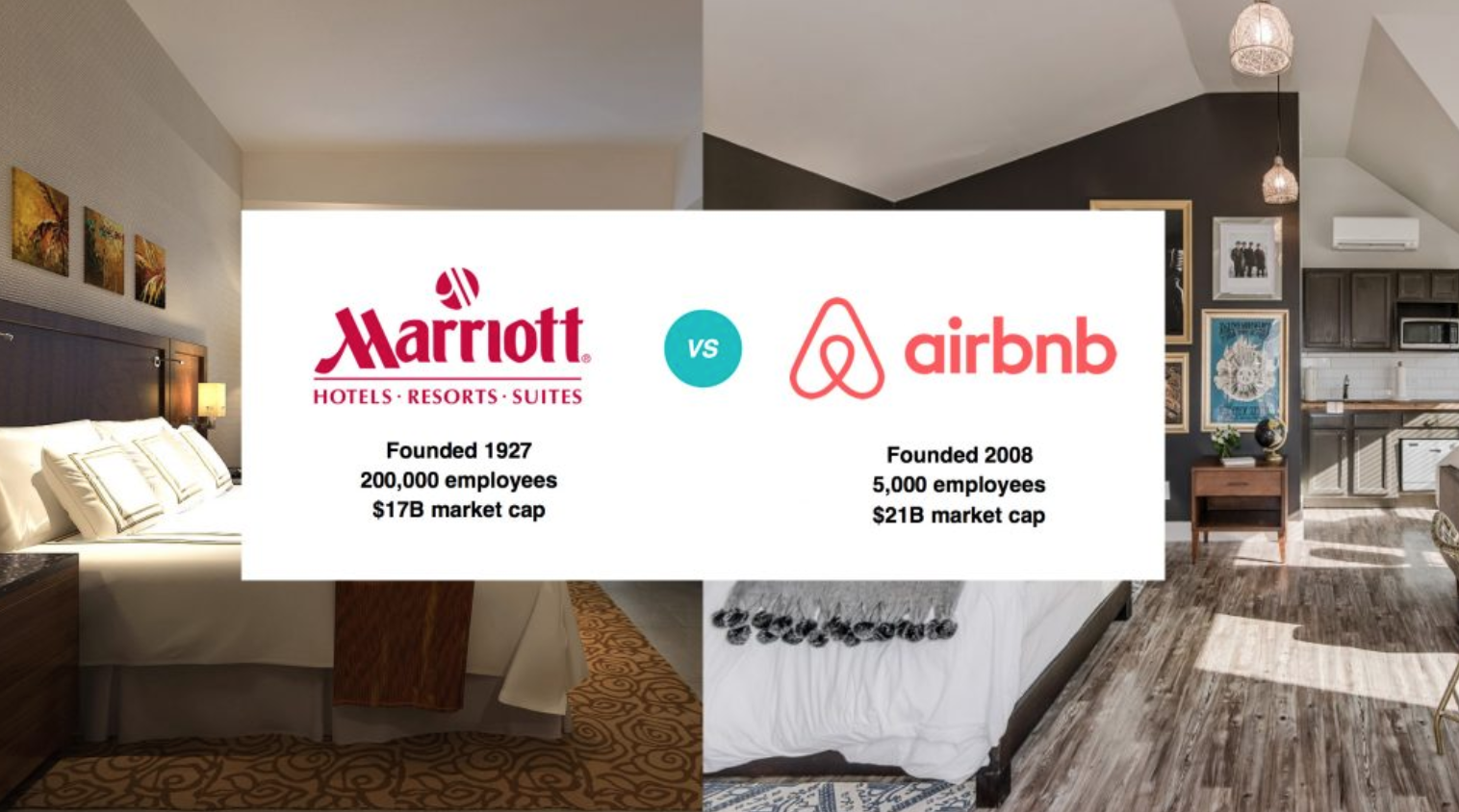

In the niche between Airbnb Inc.’s home rentals and traditional hotel rooms, a new breed of startup is offering a hybrid option aiming to merge the best of both worlds.

Companies like Domio, Lyric and Sonder lease a number of floors in commercial or residential buildings, stock them with comfy furnishings, then rent them out for short-term stays.

These companies are betting that some guests are growing wary of Airbnb, where experiences and services can vary depending on the host and in some cases can run afoul of local laws. But they also believe many travelers would prefer the comfort of an apartment over a standardized hotel room.

The unpredictability of small-time hosts is a “problem that doesn’t improve over time like an algorithm,” said Jay Roberts, Domio’s chief executive officer.

An Airbnb spokeswoman said the company has been working on partnerships with real estate owners across the country. The company has also been expanding its offerings, in part to ensure high-quality stays, for example with a program that includes only top-rated hosts.

These startups won’t have the field to themselves for long. Big hotel operators are also starting to offer so-called apartment hotels—professionally managed accommodations in private residences or commercial buildings—as alternatives to the individual host model popularized by Airbnb and Expedia Group Inc.’s HomeAway.

Marriott International Inc. announced a new home-rental business last week that would include 2,000 high-end homes in 100 markets across the U.S., Europe and Latin America. The company says it is working with property managers to ensure hotel standards for safety and service.

Even Airbnb is experimenting with a similar approach. The company recently announced a partnership with real estate owner RXR Realty to turn 10 floors near the top of a Rockefeller Center office tower into hotel-like accommodations, the first of what the partners hope will be several in New York.

New York City-based Domio, meanwhile, recently opened its first location in New Orleans, in a venture with investment firm Upper90. Units look like conventional apartments but are rented out by the night at rates starting at $149. Perks include a kitchen and access to washing machines and a rooftop pool, along with hotel-room staples like cable TV and free toiletries. Founded in 2016, the company is in negotiations to open another 15 apartment hotels, with more in the pipeline.

Sonder, which like Airbnb is based in San Francisco, has raised $135 million in venture capital and is close to raising more in a new round at a valuation of around $1 billion. The company recently opened a short-term rental location in Manhattan’s financial district.

Some cities’ restrictive short-term rental laws are shaping competition in the industry, where typically only licensed hotel operators are permitted to offer lodgings by the night.

New York City has some of the strictest such rules in the country, barring people from listing entire apartments for rent for less than 30 days. Sonder says its property isn’t affected by the law because it is built to hotel code, with tweaks like fire alarms that include an announcement system and wider staircases.

The regulations are one reason why Airbnb—which built a company valued at $31 billion by relying on millions of individual hosts to list their homes for rent—is increasingly interested in the apartment-hotel industry, according to people familiar with the company. It is also part of Airbnb’s plan to diversify its business ahead of a planned initial public offering, which bankers expect next year.

Last year Airbnb dispatched Alex Ward, of its real-estate team, to New York to help solve the company’s supply problem in the city and warm the local real-estate industry to potential cooperation, according to people familiar with the effort.

Airbnb held talks with several startups, including Domio and Lyric, a luxury-rental startup catering to business travelers with hotel services like room cleaning and 24-hour customer support, say people familiar with the matter. Airbnb discussed providing financial backing to startups to lease buildings, and in return the units would be listed exclusively on its site, these people said.

While Airbnb didn’t reach a deal, it is leading a $160 million round of debt and equity funding for Lyric.

Lyric’s CEO, Andrew Kitchell, said many of the companies looking to open apartment hotels will realize they need a specialized operator and seek to join with Lyric, which currently operates around 400 apartments and hopes to expand to 2,000 over the next 12 months.

“It’s the sort of thing that sounds easy,” he said, “but is extremely hard to do.”

Some real-estate firms are betting they are well-positioned to enter the fray. Related Companies is working on short-term rentals at one of its San Francisco properties starting this summer, Nicholas Vanderboom, chief operating officer of Related California, said. The developer plans to set aside 10% of the building’s apartments for short-term use.

Customers will have to book for at least 30 days to comply with local laws, and Related said it is targeting some guests who might otherwise stay at a hotel for an extended period, such as business travelers or those visiting other properties while planning a move. Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts, Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts

How Can Apartment-Hotel Startups Compete With Big Corporations Like Marriott And Airbnb? Join The Conversation.

Updated: 11-11-2019

Airbnb Now Bookable With Bitcoin and Lightning Network Via Fold App

Bitcoin payments app Fold now supports home-sharing giant Airbnb, the firm announced on Nov. 11. Now Fold users can get 3% back in Bitcoin (BTC) on every stay and experience booked on Airbnb.

$25 And $100 Airbnb Gift Cards For Bitcoin

Airbnb is now listed on its rewards program called Fold Kickbacks. The program supports Bitcoin’s second layer Lightning Network (LN) allowing to buy gift cards for Bitcoin with 3% cashback. Currently, Fold offers $25 or $100 gift cards on its website.

Launched in July 2019, the Fold Kickbacks program already supports some big-name retailers including Amazon, Starbucks and Uber. However, the app works in selected countries including the United States, Australia, Canada, Ireland, Mexico and the United Kingdom, depending on the specific brand. The firm expects to roll out services in Europe in the near future.

In late September 2019, Fold raised $2.5 million in order to expand its platform with a fiat currency payment option. The new feature was added in late September 2019 and allows Fold users to spend both fiat currency and Bitcoin at online and in-store retailers by adding their credit card or Bitcoin Lightning wallet. To date, Fold app only accepts Bitcoin, the firm says.

More And More Ways To “Stack Sats”

But while Fold is one of the oldest Bitcoin shopping rewards apps today first launched in 2014, it is certainly not the only one as many other options to “stack sats” are becoming available.

Lolli, another Bitcoin rewards shopping app, previously partnered with American pet retailer Petco in late August.

Lolli also rolled out support for major American grocery chain Safeway to provide customers with 3.5% cashback in Bitcoin on all their purchases.

Elsewhere, Japan’s largest gift card platform Amaten announced its plans earlier this year to issue tokenized gift cards in partnership with blockchain network provider Aelf.

Updated: 12-27-2019

What It’s Really Like to Be an Airbnb Landlord

People who are doing explain the ups and downs—and what you need to do to make it pay off.

Can you make your extra space earn its keep? Many people with more house than they need are turning to Airbnb and other services to rent out extra rooms, or even their whole house, to bring in cash—often to cover their mortgage or other critical expenses.

But the process isn’t as simple as putting up a listing. Often, it takes a pricey renovation to make the house appealing to renters, and then there are ongoing costs like restocking soap and hassles like taking care of laundry. Occasionally, the guests leave the space a lot worse than they found it.

How much you can make depends on a number of factors, including location, seasonality and government regulations, which vary depending on the locality. And your margins often depend on how much of the work you’re prepared to do yourself, and how much you contract out to workers such as housecleaners.

Here’s a look at some people who have taken the plunge into short-term renting—along with the nuts-and-bolts math of how they have tried to make it work.

One Bedroom—And Sometimes The Whole House

A few years ago, Kevin Ha, a 32-year-old former lawyer who runs the website Financial Panther, moved into a four-bedroom home in Minneapolis with his wife, Caitlin. (His dog, too.) Not long after, Mr. Ha decided he would list one of the rooms on Airbnb. It was already furnished, he reasoned, and would otherwise have sat empty.

Mr. Ha soon discovered that there was demand in his area—he lives near the University of Minnesota and could attract conferencegoers and graduate students in town for medical-school interviews, charging $50 or $60 a night on average.

Proximity to such locations is one major factor that can help determine the success of a short-term rental, according to Symon He, a co-author of the forthcoming “Airbnb for Dummies” and a founder of the advice website LearnBNB. “Typically, you’re going to be better off with a traditional rental if you don’t have a great location,” he says, referring to long-term leases in which tenants pay by the month to rent out a unit. “Demand is dictated by location.”

Still, a steady stream of guests can bring its own set of issues. At first, Mr. Ha says, he was in the habit of messaging each guest individually in making arrangements for their stay. Now he has automated such messages using a third-party app called iGMS, which sends out introductions, reminders and checkout procedures.

To streamline the operation further, Mr. Ha has written a house manual that guests can consult during their stay. In it, he includes details about his home that might confuse visitors, such as the fact that the temperature indicators on his shower knob are reversed.

Although Mr. Ha does occasionally feel as if he has lost some of his privacy by regularly giving up a bedroom to strangers, it hasn’t been much of an issue. Most of his guests, he says, don’t even leave their rooms when they are home.

Last year, Mr. Ha began listing his entire house, and now typically rents it out for two or three days at a time. At those times, he goes on short trips—paid for by the proceeds of the rental. He usually charges about $225 to $300 a night for the house, though there are occasions when he can charge much more. For instance, during the Super Bowl, held in Minneapolis in 2018, Mr. Ha raised the nightly rate to $1,250.

Among his expenses, Mr. Ha pays $50 a for a license that allows him to rent his entire place, and to help set prices, he uses a dynamic-pricing app called Beyond Pricing, which charges a 1% fee for each booking.

He estimates that he will make about $16,000 this year through Airbnb, which just about covers his mortgage. Because Mr. Ha does the cleaning himself—and because he didn’t need to buy any new furniture when he began listing his home—he says that his profit margins are high. “I’d reasonably argue that my margin is 100%, since the cleaning I do is cleaning I would already do anyway.”

In Search Of Money And Company

When Bonnie Walsh moved from her home in Conifer, Colo., to a 23-acre farm in rural Madison, Va., about four years ago, her plan was to retire. But Ms. Walsh quickly found that she was lonely—her husband, Bruce Smith, often travels for work—and that maintaining such a large property was more expensive than she had anticipated. “The farm needed an income,” says Ms. Walsh, who is 58. After some deliberation, she decided to give Airbnb a go.

Making preparations to list her home were complicated. For one thing, she spent three years making renovations to get the rooms ready for guests. And it was difficult to find the proper homeowners insurance. While Airbnb offers its own liability insurance, Ms. Walsh felt it was a good idea to get more protection, but most insurance companies would insure her home only if she planned to rent all of the rooms out to one party at a time, she says.

It took multiple phone calls for Ms. Walsh to land an insurer that would let her rent out four rooms—three with queen beds and one that has four single beds—individually.

After she was set up, though, her rental operation took off quickly. Within half an hour of listing, she had booked two rooms.

Ms. Walsh, who operates solo, runs her home like a bed-and-breakfast, doing all the cleaning herself and fixing breakfast for her guests. Initially, Ms. Walsh chose not to build B&B services into the fee, opting to remain competitive with other Airbnbs in the area that didn’t offer home-cooked breakfasts. But since establishing herself, Ms. Walsh says she now plans to raise prices a bit in the new year.

Currently, she charges $130 a night for the suite, which has its own bathroom. The two other rooms with queen beds go for $90 a night, and the bunk room goes for $135. (These rooms all share a bathroom.) To book all four rooms, she charges $430.

Her margins, she says, are strong, since she rents out more than one room at a time and hasn’t hired anyone else to help her clean or run the business. For cleaning, she spends only about $50 a month, which includes cleaning supplies and shampoo, conditioner and body wash in refillable containers. Sheets, towels, pillows and comforters were a one-time purchase of about $2,500.

Ms. Walsh has embraced her role as a de facto B&B operator. She doesn’t feel as if she has lost any of her privacy because she lives in a wing of the house that can be completely closed off from the larger area in which guests stay. In fact, she enjoys meeting her guests and hearing their stories—it has even helped cure her loneliness.

Still, being a host isn’t for everyone, according to Daniel Rusteen, an accountant who runs the website Optimize My Airbnb. If you know you won’t be able to embrace customer service, then running a short-term rental may not be for you. Even one bad review, Mr. Rusteen says, can do serious damage when it comes to booking guests.

Since June, Ms. Walsh has made more than $20,000 through Airbnb. The money, which covers upkeep on the farm, came just in time to cover some particularly high bills, she says. Now, given her newfound revenue stream, she is building two new cottages on the property with the intention of listing them by spring.

An absentee host

When Alex Golubev bought his three-bedroom Seattle home in 2012, he felt as if it were time to settle down. Instead, Mr. Golubev, now 40, realized after a couple of years that he wanted to travel, so he set about making arrangements to list his home on Airbnb.

Mr. Golubev, who works as a freelance financial consultant, finally put his entire home up for rent in the summer of 2016, at a rate of $376 a night. He saw returns relatively quickly.

In one week that August, he raked in around $2,600. Encouraged by the money he was making, Mr. Golubev decided to commit to life as a digital nomad, traveling the world and working remotely most of the time while renting out his home on Airbnb. In 2018, he was gone for 281 days and made $60,000. This year, Mr. Golubev is on track to earn $70,000.

Mr. Golubev estimates that his net earnings amount to about half of what he brings in, after accounting for his mortgage, insurance and other expenses such as toilet paper and cleaning supplies. He also employs a manager to handle a range of jobs while he is away—from greeting guests to restocking supplies of morning snacks and coffee—for 12% of the cost of the stay plus $100 for one cleaning per stay.

Still, the money earned, Mr. Golubev hastens to add, is well above what he might make renting out the house long term. For that, he says, he’d bring in around $3,300 a month, which would only amount to half of what he makes through short-term rentals with Airbnb.

One challenge has been attracting guests during Seattle’s more inclement months, when tourism drops. With that in mind, before he became an Airbnb host, Mr. Golubev took measures to furnish his home with the kinds of trappings that could lure guests during the off-season.

For example, he installed a hot tub and put in a big, comfortable couch, amenities he would never have bought for himself. He has found that they do serve as an enticement, as guests often inquire about them before booking.

Big renovations, disappointing income

Robert and Leslie Kasnak, who own a small furniture-restoration and design business in Brownsburg, Ind., just outside Indianapolis, discovered Airbnb about five years ago when a client mentioned that he was going to prep an Airstream on a lot beside his house and rent it out to visitors. At the time, they were both in their 60s and ready to slow down.

They wanted to generate a passive income stream and rely more on their savings, so they set about renovating their home to accommodate guests on Airbnb, remodeling two bedrooms and an entryway along with installing a new bathroom in the family home in which they had raised four children to adulthood.

The renovations were costly—$54,000—but the couple justified the expense by reasoning that it was necessary if they ever wanted to sell the house, which is about 40 years old. Mr. Kasnak had initially estimated that they would take in about $20,000 a year, but their annual income from Airbnb has only amounted, on average, to about half of that since they began listing the bedrooms in 2016.

According to Mr. Kasnak, this is “pretty easy money” compared with doing work in his shop because it requires much less labor and overhead. To clear the same amount of profit in his woodworking business, he says he would need to gross approximately $30,000. They don’t mind sharing the house with strangers, either, as they have experience with face-to-face customer service. Most guests, Mr. Kasnak says, don’t emerge from their rooms that often anyway.

Still, revenue isn’t as much as Mr. Kasnak and his wife had anticipated, and they have not yet recouped the money associated with the renovations. This hasn’t really hurt them financially, Mr. Kasnak says, but it has been somewhat disappointing. They now expect to make the money back by the end of 2020 or early in 2021.

One way they are cutting costs is by managing the rooms on their own. Hiring a property manager to take care of things can cost you about 15% of your revenue, though it can save a lot of headaches, according to Evian Gutman, the founder of Padlifter, an online marketplace for short-term rental providers. The Kasnaks’ accountant also helped them set up their Airbnb business as a limited-liability company, making it simpler for accounting purposes to deduct a share of expenses from their residence, Mr. Kasnak says.

But to make things work financially, Mr. Kasnak thinks that he and his wife will have to give up their bedroom, which has its own bathroom, and move into their finished basement for about a year. Mr. Kasnak describes this as an “exploratory measure.” Currently, the two bedrooms that are listed share a bathroom, which Mr. Kasnak believes may deter some guests from booking a room. If traffic increases by offering a private bathroom, the Kasnaks plan to build a new bathroom in the bottom-floor suite.

The Pros And Cons Of Living With Strangers

Three years ago, 46-year-old advertising executive Tamara Swager decided to put two of her bedrooms on Airbnb to cover some home-remodeling costs. Ms. Swager, who lives with her husband and two children in a seven-bedroom home in Long Beach, Calif., has found that their house attracts a number of guests because it is in proximity to several highly trafficked destinations, including an airport and a convention center.

Last year, Ms. Swager and her husband, Anthony, made $32,000 in total, and this year, after having raised prices a bit, they have made $52,000 through the beginning of October. That money doesn’t cover their mortgage, though it will cover the remodeling by the end of the year, Ms. Swager estimates. Overall, Ms. Swager says, bottom-line revenue is decent, though she adds that the taxes associated with Airbnb can be onerous, particularly in California.

The tax element isn’t something that a lot of people keep in mind when they dive into Airbnb, according to Miguel Alex Centeno, founder of Tax Hack Accounting Group. But it is one of the most important things to stay on top of, he says. For instance, it can be difficult to know what you can and cannot deduct. You can’t deduct big renovations and expensive purchases like appliances and furniture, Mr. Centeno says, but you can deduct items more directly associated with the Airbnb business such as linens and coffee for guests. “You’d be surprised how the Keurig cartridges add up,” he says.

Ms. Swager says she is on top of her taxes, but she is finding problems that are common to many hosts. For one, toiletries and complimentary oatmeal and coffee have cut into earnings, as have certain unexpected damages, including shattered chandeliers and burned carpets. “The number of times that I go in and the room smells like weed is not infrequent,” says Ms. Swager, who tries to maintain a marijuana-free home even though the substance is legal in California.

The process of running an Airbnb, she says, has made her a bit more “cynical,” but also made her more discerning, and she now vets guests more thoroughly.

Living with strangers requires something of a “mental adjustment,” Ms. Swager says, but because she has previously employed au pairs who have stayed in her home, she and her family were conditioned for Airbnb.

Ultimately, though, there are benefits to hosting beyond monetary gain, Ms. Swager says. She and her family have hosted visitors from more than 80 countries, and Ms. Swager’s children constantly learn about geography and culture from visitors. Ms. Swager keeps a big map on which she asks guests to plant a small flag showing where they are from. “It’s been great,” she says, “for my kids to have exposure to a variety of cultures.”

Updated: 6-2-2020

Rental-Apartment Operator Greystar Bulks Up

Firm to buy Alliance Residential business that manages nearly 130,000 housing units, widening U.S. lead.

Greystar Real Estate Partners LLC said it is acquiring a business that manages nearly 130,000 housing units, a deal that extends Greystar’s position as the country’s largest operator of rental apartments.

The Charleston, S.C.-based firm is buying the business from Alliance Residential Co., the country’s fourth-largest apartment manager. Alliance intends to remain in the apartment-development and -investment business.

The acquisition brings Greystar’s management inventory to 660,000 units, adding to the company’s large footprint in Phoenix, Los Angeles, Houston and Seattle.

Greystar paid nearly $200 million in the all-cash deal, according to people familiar with the matter, making it one of the largest apartment-related transactions during the coronavirus pandemic and economic fallout.

Negotiations between Greystar Chief Executive Bob Faith and Alliance Chairman Bruce Ward began in February, when concern was growing about the new virus but before its spread had been declared a global pandemic. Mr. Faith said Greystar would have been able to back out of the deal in recent weeks.

Greystar opted to press forward at the previously agreed-upon price because the company is confident that the rental-apartment business will stay strong over the long run, despite “some short-term headwinds” caused by the health crisis, Mr. Faith said.

Rental apartments have been one of the strongest commercial-property types over the past decade, thanks in part to the shift by millions of households to renting from owning. Rent increases have outpaced the rate of inflation for most of the decade.

The pandemic has cut into revenue as tenants have lost jobs, and it has raised business expenses as companies try to protect staff and tenants from exposure to the virus. Some cities and states have imposed eviction moratoriums that have enabled renters to skip payments.

But the impact, so far, hasn’t been as severe as expected, especially among higher-quality apartment buildings. “Pressure on apartment rents and occupancy should accelerate, but initial estimate cuts proved too harsh,” Green Street Advisors said in a report last week.

Launched by Mr. Faith in 1993, Greystar also develops and buys apartment buildings. The company owns about 140,000 units in addition to managing apartments for third-party owners.

Most of Greystar and Alliance’s apartments are on the higher end of the market, with tenants who are more likely to have kept their jobs through the economic disruption and paid rent. The combined company collected about 95% of its April and May rent, off slightly from the 99% on average in months before the pandemic, according to Greystar.

“We’re in a pretty good spot,” Mr. Faith said. “It means that folks are either making good income or have good savings.”

He added that there are enormous benefits to scale in the apartment-management business when it comes to such things as buying supplies, gathering data and hiring employees. “When you’re the largest manager in Phoenix or Los Angeles or the [San Francisco] Bay Area, the top talent in that region wants to work for you,” Mr. Faith said.

Greystar has been building the size of its management portfolio to offer smaller owners the advantages of its scale.

“This is how consolidation is happening in this industry,” Mr. Faith said. “A lot of real-estate owners that own and manage their properties look up one day and say, ‘I’m not making a lot of money [at management]. I’m going to give it to Greystar.’”

Updated: 4-15-2021

Forget Boise. Buy Rental Properties In These Cities

Consider Salt Lake’s demographics, Birmingham’s stability and Nashville’s affordability.

There’s a lot of competition right now for single-family homes across the U.S. — from buyers hunting for new primary living spaces to institutional investors looking to capitalize on limited supply.

It can feel overwhelming if you’re in between: An amateur real estate investor looking to put extra cash to work by acquiring a second or third home to rent out.

Rest assured, as the spring selling season kicks off, it’s still a good time to invest in a home for the usual reasons. Done correctly, real estate can diversify a portfolio and act as a hedge against inflation. Plus, given the difficulties would-be first-time homebuyers are facing, and the desire for more space spurred by the pandemic, demand for renting houses is likely to stay high.

Not surprisingly, a Google search for “invest in real estate” is the highest it’s been since 2004, Freddie Mac’s deputy chief economist Len Kiefer noted on Twitter recently.

Still, given how hot the housing market is nationwide, and the rapid, eye-popping price jumps in some cities, investors need to proceed with caution. The best places for long-term investment are ones where home price growth and volatility aren’t outliers compared with national averages, and offer some kind of stability on their own, such as universities, or some type of commerce.

Buying close to home has practical advantages and may feel safer, but it may not be the smartest investment.

Here are a few examples of cities to consider, and one to avoid, using data provided by Zillow.

Nashville: The allure of this Tennessee city and its amenities isn’t new, but now may be a particularly good time to invest. Home values over the past 12 months ending in February have increased 9.6% relative to the national average of 9.9%. Prepare to spend several hundred thousand dollars, as the average home price in Nashville is about $311,000, compared with the national average of $272,000.

Also, year-over-year rent growth slowed for most of 2020, but seems to have bottomed out in January, ticking back up by 1.6% in February to $1,600, slightly below the typical rent nationally of $1,700.

Birmingham: It’s the most populous city in Alabama, and home to several colleges, law schools and a robust health-care industry. The draw here is its stability and affordability. Birmingham’s year-over-year rent growth stayed relatively constant, even as it softened during the pandemic in other parts of the country. The typical rent is $1,140.

Salt Lake City: Utah’s capital has one of the nation’s largest population shares of Generation Z — those in their teenage years and early 20s — who are likely to rent now or start renting in a few years. Companies including Zions Bank and Overstock are headquartered there, and many more corporations have outposts in the region.

Home prices have jumped quite a bit this year — 15% — and the typical home is valued at $440,100. But that’s well below the average in other Western metro areas that have attracted Bay Area transplants, such as Denver and Portland. If Salt Lake still feels overpriced, consider the nearby cities of Provo (where Brigham Young University is located) and Ogden, which are cheaper.

Boise: Idaho’s capital is the city to be wary of unless you’re intent on moving there yourself. It leads the nation’s top 100 metro areas in rent growth and home value growth. Rents are up 12.6%, and home values have jumped 26.5% as of February, compared with a year earlier. (Spokane is No. 2 for rent growth at 10.6%, and Phoenix is No. 2 for home value growth at 18.3%).

While rents are still relatively affordable in Boise at $1,470, homes are now hovering around $411,000. Such rapid growth seems unsustainable, especially as questions about the permanence of working from home are raised.

Of course, there are options besides cities and suburbs. And figuring out the where is just half of it; investors then also have to think about the neighborhood, says Steven McCord, a real estate investor who co-founded Locate Alpha, which provides city and sub-city analyses.

There are a few other things to keep in mind when weighing a residential real estate investment. It’s probably best to avoid beach towns given the maintenance involved, the potential for weather damage (meaning, high insurance costs) and short-term tenants who may not treat the property as well as long-term renters would.

Also, make sure you’re aware of the local laws and how friendly they are to renters, as well as property tax liabilities. Decide whether you want to be in charge of maintaining the property (and fielding late-night calls about hot water problems) or if you’ll tap a property manager. If the latter, figure that will eat up as much as 20% of your income stream.

Finally, remember that interest rates, while still historically low, are likely to rise. That tends to have a delayed, negative effect on home prices, which makes choosing the right city to buy a home to rent out even more important.

Updated: 5-3-2021

Marriott Eyes Rewards, All-Inclusives In Cautious Travel Rebound

In the wake of a new CEO and the Covid-19 crisis, executive Tina Edmundson says the way we travel is changing before our eyes.

If thinking about Marriott International conjures the skyscraping Marquis flagship in New York’s Times Square, with its supersonic bubble elevators currently presiding over a dark Broadway, it would be easy to assume that the company faces a bleak near-term future. Indeed, parts of that company’s business are still struggling to find footing amid a travel slowdown that has lasted more than a year.

At the Marquis, 800 jobs were eliminated around the year-end holidays. As a whole, Marriott International suffered its worst year in recent history in 2020. It also lost its visionary chief executive officer, Arne Sorenson, to pancreatic cancer.

But for Marriott, as for much of the travel industry, things are turning up, and pockets of opportunity are becoming clearer. Shortly after the announcement of its new CEO, Anthony Capuano, in mid-February, shares for the company rose to $157.50 and have since remained steady—a sharp departure from where things stood in May 2020, when they were just above $75.

“It’s hard to make predictions about what will come next,” says Tina Edmundson, Marriott’s global brand officer, who adds that travel has evolved in the past year, from an indulgence to “a primal need.”

Expanding Beyond Hotels

Currently, Edmundson is shepherding the growth of a new sector devoted to rental homes called Marriott Homes and Villas, which debuted in 2019 as a far-cry competitor to Airbnb Inc. What started as a portfolio of 2,000 homes has grown to more than 25,000. (Airbnb maintains about 7 million rentals on its site.)

Edmundson frames the foray as less an attempt to rival Brian Chesky’s home-sharing unicorn and more about extending the ability to earn and redeem loyalty rewards in any travel scenario. “The goal is to really fill out our portfolio of options for our members,” she explains. “It’s not our desire to have millions of homes. It’s our desire to have a curated portfolio.”

Edmundson says Homes and Villas was “certainly advantageous” over the last 14 months, when privacy became the amenity with the greatest premium. “But on balance, we have 7,500 hotels, so it’s not anywhere near the scale of our true core product.” Rather than help the company weather the storm, it was a way to keep its Bonvoy members engaged while they were otherwise unable to travel.

All-Inclusives Go Luxe

Many think of all-inclusive resorts in four letter words. But these offerings have long been evolving, with even the main players—such as Club Med and Paradisius—finding ways to attract the next generation of travelers.

Marriott is joining their cause. The acquisition of 19 Blue Diamond Resorts around the Caribbean represents more than 7,000 new hotel rooms for the company; Edmundson says the aim is to have 33 resorts by 2025.

The acquired resorts will be converted into all-inclusive versions of Ritz-Carlton, Luxury Collection, and Westin, among other Marriott luxury brands. “When you think about a Ritz-Carlton all-inclusive, I don’t want you to think about an all-inclusive, I want you to think of an amazing Ritz that happens to be inclusive of every desire you might have,” she explains. “There’s some negativity around that space, but we are setting out to craft and curate something that doesn’t exist.”

Of course, it does exist: All-inclusive resorts such as Jumby Bay and Carlisle Bay in Antigua cost upward of $1,300 a night in exchange for a vacation in which you never have to think about being nickel-and-dimed. But they are few and far between.

Each all-inclusive, Edmundson adds, will have brand extensions that relate to its parent’s roots: Westin will be the wellness-oriented all-inclusive, for example. The challenge will be educating anyone unfamiliar with these draws—and convincing guests to generally stay put on a resort, rather than using it as a home base for self-designed explorations.

A Touch-and-Go 2021

Travelers are currently caught between a strong desire to cross things off bucket lists while needing to navigate ongoing border restrictions. That pull, she says, encouraged people to book more “drive-to” trips before learning that the EU would soon admit entry to certain vaccinated travelers.

“The drive market will last through the year,” she predicts, speaking of both Europe and the U.S. “I think that as borders open up, it’s going to be restrictive still for a little while, given the extra hassle of Covid tests and vaccine passports.”

All this is encouraging the discovery of second cities, says Edmundson, and will give mountain and resort destinations continued importance for another year. She cites unmatched off-season business in places from Aspen, Colo., to Deer Valley, Utah, where summer bookings are pacing 97% ahead of last year, driven by strong transient demand.

She remains cautious about international travel. “This morning, while I was on my Peloton, I saw that 8% of Americans missed their second vaccines. So that’s going to be the most important thing, getting the vaccinations so that as borders open, we can have a good show,” she says.

What Comes Next

Edmundson expects the flexibility of work-from-home to persist, reshaping people’s vacation schedules and flattening the “peaks and valleys” destinations typically see in terms of visits.

“I don’t think things will go back exactly to 2019 trends or patterns,” she elaborates. “People have developed an appreciation for what is in their backyards—to explore beyond the big cities—and that will also trigger a redistribution of where people go.”

That connects with the growth of “purposeful travel,” or trips that come with a heightened consciousness of environmental and cultural impact. “This time we’ve had—the 12 to 14 months of being in our basements in front of Zoom calls—it’s made people confront what their personal impact is on the places they visit, and on wanting to leave those places better than they found them.”

She says none of this is new, but it’s more urgent—just like the fight for diversity and inclusivity across the industry, for which the departed CEO Sorenson strongly advocated. In his memory, the company has created the Arne M. Sorenson Hospitality Fund and endowed it with $20 million through its philanthropic arm, the J. Willard and Alice S. Marriott Foundation.

As part of that effort, it has also partnered with Howard University to establish the Marriott-Sorenson Center for Hospitality Leadership as a means for developing a pipeline of BIPOC talent.

Perhaps a more ephemeral silver lining is rediscovering the joys and luxuries of hospitality in any form. “After a year of not traveling, they’re going to find themselves highly sensitized to it,” says Edmundson. “The anticipation of what you haven’t done in so long makes you long for that feeling. And that’s going to be fun.”

Updated: 8-13-2021

How To Compete In The Big City’s Resurgent Rental Market

There are lessons that apply everywhere in the heated U.S. market. But would-be renters need special tools as well as a lot of money if they’re set on Brooklyn.

In just a few months, the rental market in many New York City neighborhoods has flipped from stagnant to red hot.

The value of move-in incentives to entice renters in Manhattan hit the lowest in a year as of July, according to appraiser Miller Samuel Inc. and brokerage Douglas Elliman Real Estate. In Brooklyn, new lease signings were the highest for a July since 2008, the report said. Apartments in desirable areas of the borough such as Brooklyn Heights and Cobble Hill are often going for several hundred dollars above the asking price, or have dozens of applicants clamoring for them, sight unseen.

While the rental prices in New York City are much higher than they are in the rest of the country, it’s a similar story of rental demand nationwide. The number of occupied rental units in the U.S. increased in the second quarter compared with a year earlier by the most since at least 1993, according to industry consultant RealPage Inc. Rents on newly signed leases in July also jumped to a multi-decade high.

So how can potential renters win out in an increasingly competitive market, especially in places like New York, where the rental process can be especially frustrating?

There are a few things an applicant can offer to sweeten the deal financially, but it’s important to remember that simply waving more money at the outset isn’t necessarily the best approach, or even allowed. Landlords want renters who are financially sound, of course, but they also want tenants who won’t be high maintenance or difficult. That’s especially true if renters are looking at smaller buildings or townhomes and dealing with owners directly.

Many apartments in New York City come with a hefty broker’s fee, which is as much as 15% of one year’s rent and typically paid by tenants. Last year, apartment owners or landlords were offering to cover the fee (even though it may have been passed onto tenants in the form of a higher rental price), but now, it’s something potential renters may want to offer to split or pay. Also, note that while there was a short-lived ban on brokers’ fees in New York City last year, they were ultimately deemed to be legal.

One tactic that won’t work: Offering several months’ rent up front. Most landlords are prohibited from accepting money in advance under their mortgage, and brokers can’t ask for it, according to 2019 New York state legislation. The same goes for trying to give a larger security deposit (typically just one month’s rent).

And even though it’s popular, renters should think twice about submitting an application for an apartment without stepping foot inside. Deals with those renters often fall through when the tenant finally comes to see the place so landlords may be wary, says Jessica Henson, a real estate agent at Compass in New York City.

In addition to the usual financial documents, it’s important in the current environment to include an introductory letter with an application, according to Vicki Negron, one of Corcoran’s top Brooklyn agents.

Keep it short and don’t reveal too many personal details so as not to violate the Fair Housing Act, which prohibits discrimination in housing. But references to attractive features of the apartment and prior rental experience or history as a tenant are advised.

For pet owners, it may be wise to include a reference letter from a former neighbor or pet sitter, who can vouch for its behavior.

The middle to end of August is a popular time for vacation, but those looking to rent an apartment for Sept. 1 or Oct. 1 would be smart to stay put so they can see units at a moment’s notice. Be flexible on viewing times, and be open to different lease start and end dates. One broker mentioned an applicant winning out because he agreed to an 11-month lease instead of 12 months.

Potential tenants should also be mindful of how they act when touring a home. Brokers for the owner or landlord will report back on things like whether someone was considerate enough to remove shoes, or just fired questions at them about water pressure and building policies.

If prospective renters are dead set on a specific building or townhome, it’s worth keeping in touch with the landlord or broker, even if they weren’t selected for the initial unit. Tenants usually have to give landlords 60- or 90-days’ notice before moving out, so owners may already know what will be available this fall. If someone is a viable applicant, the landlord may just wind up renting to him or her directly rather than go through the hassle of listing the apartment.

If time is of the essence, renters may want to consider a short-term furnished rental or Airbnb until the market cools off. They may also want to re-evaluate their wish lists — maybe a washer/dryer in the unit isn’t so essential — and neighborhood searches.

Finally, prospective renters may want to run the numbers to see if buying an apartment, especially with interest rates still so low, makes more financial sense. If so, they’ll be in a good position to rent their homes one day and take advantage the next time the rental market is on an upswing.

Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts,Airbnb, Marriott Battle Upstarts

Related Articles:

Smart Wall Street Money Builds Homes Only To Rent Them Out (#GotBitcoin?)

New Ways To Profit From Renting Out Single-Family Homes (#GotBitcoin?)

Home Prices Continue To Lose Momentum (#GotBitcoin?)

Freddie Mac Joins Rental-Home Boom (#GotBitcoin?)

Retreat of Smaller Lenders Adds to Pressure on Housing (#GotBitcoin?)

OK, Computer: How Much Is My House Worth? (#GotBitcoin?)

Borrowers Are Tapping Their Homes for Cash, Even As Rates Rise (#GotBitcoin?)

‘I Can Be the Bank’: Individual Investors Buy Busted Mortgages (#GotBitcoin?)

Why The Home May Be The Assisted-Living Facility of The Future (#GotBitcoin?)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.